Introduction to the Securities Litigation Process

- The securities litigation process: Begins with filing a Complaint detailing the alleged violation of securities laws, followed by a Discovery phase to exchange evidence and information.

- Pre-trial motions: The parties may then file pre-trial motions or engage in settlement discussions before a potential trial where a judge or jury decides the case.

- Alternative dispute resolutions: Securities mediation can also occur, and many cases are resolved through medication, which may then involve a lengthy Claims Administration process to distribute funds to affected investors.

1. Investigation and Filing the Complaint

- Investigation: Before a lawsuit is filed, thorough investigation is needed to gather facts and determine if a viable claim exists.

- Complaint: A formal complaint is drafted and filed with the appropriate court, outlining the factual basis of the claims and the legal theories supporting them.

- Class Period: For class action lawsuits, the “class period” is established, defining the time frame during which the alleged fraud or violations occurred.

2. Discovery

- Information Exchange: This phase involves both parties exchanging information and evidence relevant to the case.

- Mechanisms: This can include depositions (out-of-court testimony), interrogatories (written questions), and requests for documents.

3. Pre-Trial Phase

- Pre-Trial Motions: Parties may file motions to address specific legal issues or to dismiss the case, in whole or in part.

- Settlement Discussions: At any point, but particularly before trial, parties may engage in settlement negotiations to resolve the dispute out of court.

4. Trial

- Presentation of Evidence: If a settlement is not reached, the case proceeds to trial, where both sides present their evidence and arguments to a judge or jury.

- Judgment: The judge or jury renders a verdict, determining the outcome of the case and potentially awarding monetary damages.

5. Resolution and Post-Litigation

- Settlement: Many cases are resolved through settlement, resulting in financial compensation for the investors.

- Claims Administration: In class action settlements, an administrator is appointed to notify the class, process claims, and distribute settlement funds.

- Case Closure: After the settlement fund is distributed and final legal documents are filed, the case is closed.

Key Alternatives & Considerations

- Securities Mediation: An alternative to court litigation, often used in securities class action to resolve the dispute..

- Individual vs. Class Actions: Investors can pursue individual lawsuits, or they can join a class action lawsuit to pursue claims collectively, which can be more efficient for large corporations.

- SEC Enforcement: The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) also brings enforcement actions for securities law violations, sometimes resulting in settlements or litigation in federal court.

Detailed Summary of the Economic, Operational, And Legal Frameworks for Securities Class Actions

Category | Key Elements | Practical Implications | Recent Developments | |

| Economic | ||||

Corporate Financial Impact | • Legal fees and defense costs | • Direct reduction in profitability | • Average settlement amounts increased 15% in 2023 | |

Operational Disruption | • Management distraction | • Reduced focus on core business | • Companies now spend average of 1,200+ hours on litigation response | |

Investor Recovery Mechanism | • Class action procedures | • Financial loss compensation | • Recovery rates average 2-3% of investor losses | |

Market Confidence Effects | • Transparency enhancement | • Investor trust restoration | • Post-litigation governance reforms implemented in 72% of settled cases | |

| Current Trends | ||||

Individual Accountability Focus | • Officer and director liability | • Executive behavior modification | • 64% increase in named individual defendants | |

Technology-Enhanced Detection | • AI-powered surveillance | • Increased violation detection | • SEC using machine learning to identify disclosure anomalies | |

Litigation Process Modernization | • E-discovery platforms | • Faster case processing | • 87% reduction in document review time | |

Cross-Border Complexity | • Jurisdictional challenges | • Multi-jurisdiction compliance | • 38% of securities cases now involve cross-border elements | |

Legal Frameworks | ||||

Pleading Standards | • PSLRA requirements | • Higher dismissal rates | • Macquarie Infrastructure Corp. v. Moab Partners (2024) reshaped omission standards | |

Loss Causation Elements | • Corrective disclosure | • Causal chain demonstration | • Dura Pharmaceuticals v. Broudo remains controlling precedent | |

Damages Calculation | • Out-of-pocket methodology | • Expert-driven calculations | • Forensic accounting techniques increasingly sophisticated | |

| Class Certification | • Commonality requirements | • Class definition strategies | • Institutional investors serve as lead plaintiffs in 58% of cases | |

Investor Considerations | ||||

Participation Decision Factors | • Loss threshold assessment | • Active vs. passive participation | • Minimum loss threshold for lead plaintiff typically $100K+ | |

Recovery Optimization | • Claims filing procedures | • Proof of transaction needs | • Only 35% of eligible investors file claims | |

Governance Implications | • Board oversight duties | • Director liability concerns | • Board-level disclosure committees now present in 78% of public companies | |

Future Participation Rights | • Opt-out considerations | • Strategic participation choices | • Opt-out actions by large investors increased 47% |

Understanding Securities Litigation: Process, Cases, and Regulatory Oversight

- Securities litigation represents one of the most complex and consequential areas of modern financial law, serving as the primary mechanism through which investors seek redress for fraudulent activities and market manipulation. This complex field has evolved dramatically over the past several decades, becoming increasingly sophisticated as financial markets have grown more interconnected and complex.

- The stakes in securities litigation cases are enormous, with settlements routinely exceeding hundreds of millions of dollars and individual cases reshaping entire industries.

- The foundation of securities litigation rests on the principle that all investors deserve access to accurate, complete information when making investment decisions. When companies, executives, or financial intermediaries violate this fundamental trust through misrepresentation, omission, or outright fraud, the legal system provides multiple avenues for recovery.

- Securities class actions have emerged as the most prominent mechanism for addressing widespread investor harm, allowing thousands of affected shareholders to pool their resources and pursue claims collectively against defendants who possess vastly superior financial resources.

- Modern securities litigation encompasses far more than simple fraud cases. Today’s legal landscape includes complex disputes involving derivative instruments, cryptocurrency offerings, environmental disclosures, cybersecurity breaches, and artificial intelligence applications.

- The pressure to “beat-the-street” has intensified dramatically in recent years, creating unprecedented incentives for corporate misconduct and, consequently, an explosion in securities-related legal actions.

THE SECURITIES LITIGATION PROCESS

| Filing the Complaint | A lead plaintiff files a lawsuit on behalf of similarly affected shareholders, detailing the allegations against the company. |

| Motion to Dismiss | Defendants typically file a motion to dismiss, arguing that the complaint lacks sufficient claims. |

| Discovery | If the motion to dismiss is denied, both parties gather evidence, documents, emails, and witness testimonies. This phase can be extensive. |

| Motion for Class Certification | Plaintiffs request that the court to certify the lawsuit as a class action. The court assesses factors like the number of plaintiffs, commonality of claims, typicality of claims, and the adequacy of the proposed class representation. |

| Summary Judgment and Trial | Once the class is certified, the parties may file motions for summary judgment. If the case is not settled, it proceeds to trial, which is rare for securities class actions. |

| Settlement Negotiations and Approval | Most cases are resolved through settlements, negotiated between the parties, often with the help of a mediator. The court must review and grant preliminary approval to ensure the settlement is fair, adequate, and reasonable. |

| Class Notice | If the court grants preliminary approval, notice of the settlement is sent to all class members, often by mail, informing them about the terms and how to file a claim. |

| Final Approval Hearing | The court conducts a final hearing to review any objections and grant final approval of the settlement. |

| Claims Administration and Distribution | A court-appointed claims administrator manages the process of sending notices, processing claims from eligible class members, and distributing the settlement funds. The distribution is typically on a pro-rata basis based on recognized losses. |

Key Players in Securities Class Actions

- Lead Plaintiffs: Individuals or entities (such as Institutional Investors) who were appointed by the court to represent the class of investors affected by the alleged securities violations.

- Defendants: The corporation, and its officers, directors, and possibly other individuals accused of securities fraud.

- Lead Counsel (for Plaintiffs): The law firm representing the lead plaintiffs and the class.

- Defense Counsel: The law firm(s) representing the defendants.

- Special Master or Mediator: In certain cases, a neutral third party may be appointed to help facilitate settlement negotiations between the parties. This usually happens if a motion to dismiss is denied and/or class certification is granted.

- Expert Witnesses: Individuals with specialized knowledge in areas like accounting, finance, or market behavior may be called upon to provide testimony or analysis.

- Class Members: The investors who have suffered losses due to the alleged securities violations and are part of the class represented by the lead plaintiffs.

- Courts: The courts oversee the legal process and ultimately approve settlements or judgments.

The Securities Litigation Process: A Detailed Roadmap

- Understanding the securities litigation process requires examining each critical stage that transforms an investor’s complaint into either a substantial recovery or a dismissed case.

- This journey typically spans several years and involves multiple decision points where cases can succeed, fail, or settle.

Lead Plaintiff Selection Process Under PSLRA

- The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (PSLRA) reshaped the scene of securities litigation. It replaced the first-to-file system with a well-laid-out process to select lead plaintiffs.

- This new approach wants to put cases in the hands of investors who can oversee class counsel with the right incentives and experience.

Definition of ‘Largest Financial Interest’ in Class Actions

- The PSLRA favors plaintiffs with “the largest financial interest in the relief sought” as the most suitable representatives. Courts review financial interest through several factors. These include total class period purchases, net class period purchases, net expenditures, and most significantly, total losses.

- The PSLRA does not specify calculation methods. Many courts use either last-in-first-out (LIFO) or first-in-first-out (FIFO) accounting principles to determine losses. This provision moves control to investors with substantial stakes, especially institutional investors.

Typicality and Adequacy Standards in Rule 23

The presumptive lead plaintiff needs more than the largest financial interest. They must meet Rule 23’s typicality and adequacy requirements. Typicality means their claims match other class members’ claims. Adequacy ensures the plaintiff’s interests align with the class and they have enough resources to oversee the litigation. Yes, it is possible to challenge this presumption if another class member proves the lead plaintiff can’t represent the class properly.

Deadline and Notice Period: 60-Day Rule

The first plaintiff must publish notice within 20 days of filing the complaint. This notice tells potential class members about the action, claims, class period, and their right to seek appointment as lead plaintiff. Class members have 60 days from publication to file a lead plaintiff motion. This required timeline eliminates the previous “race to the courthouse” in securities litigation.

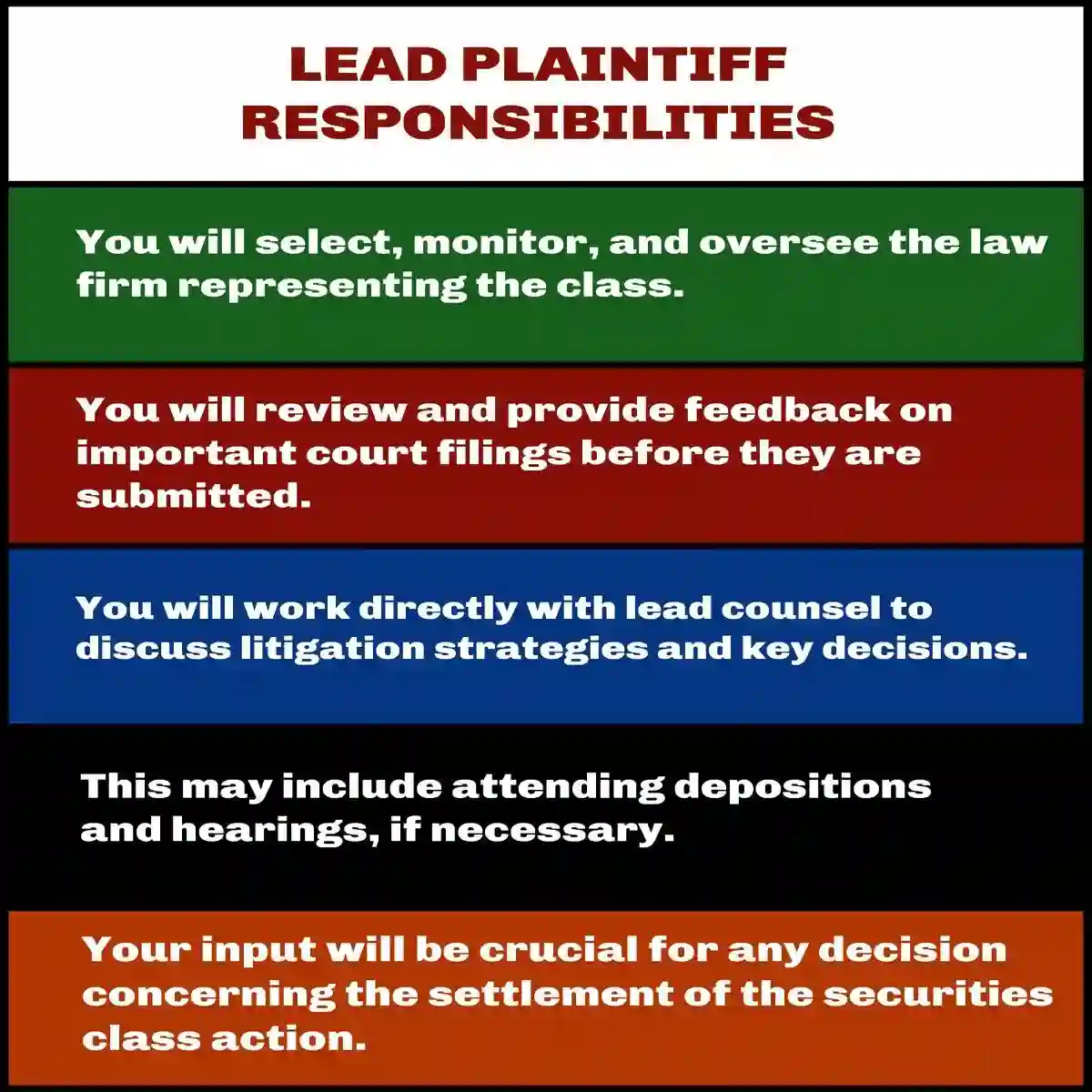

The Responsibilities the Lead Plaintiff Will Have

- Overseeing lead counsel: You will select, monitor, and oversee the law firm representing the class.

- Reviewing legal documents: You will review and provide feedback on important court filings before they are submitted.

- Discussing strategy: You will work directly with lead counsel to discuss litigation strategies and key decisions.

- Potential participation in legal events: This may include attending depositions and hearings, if necessary.

- Input on settlement decisions: Your input will be crucial for any decision concerning the settlement of the securities class action.

Motion to Dismiss: The First Critical Hurdle

The motion to dismiss stage represents the defendant’s initial opportunity to eliminate the case entirely before expensive discovery begins. During this phase, defendants argue that even if all allegations in the complaint are true, the plaintiffs have failed to state a valid legal claim.

Courts scrutinize whether the complaint adequately alleges material misstatements or omissions, demonstrates that defendants acted with the required mental state (typically “scienter” or intent to deceive), and establishes that the alleged misconduct caused investor losses.

Recent statistics demonstrate the critical importance of surviving this stage. Approximately 60% of securities class actions face motions to dismiss, and roughly 40% of these motions succeed in eliminating all or substantial portions of the case. The quality of the initial complaint often determines whether investors will ever have the opportunity to recover their losses.

CIRCUIT BY CIRCUIT COMPARISON ON STANDARD FOR PLEADING SCIENTER

Circuit | Summary of Pleading Standard | Key Cases | Notes and Circuit Splits |

| First Circuit | Requires strong inference of scienter under PSLRA standards. Accepts allegations of motive and opportunity combined with strong circumstantial evidence. | Greenberg v. Crossroads Systems(2020); In re Biogen Securities Litigation(2019) | Aligns with majority circuits requiring “strong inference” but more lenient on motive and opportunity allegations than some circuits. |

| Second Circuit | Applies “strong inference”standard with emphasis on holistic analysis. Requires inference of scienter to be at least as compelling as any opposing inference. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights(2007); ATSI Communications v. Shaar Fund(2021) | Leading circuit on scienter interpretation post-Tellabs. Emphasizes comparative plausibility of inferences. |

| Third Circuit | Follows Tellabs standard requiring strong inference that is cogent and compelling. Accepts core operations doctrine in limited circumstances. | In re Hertz Global Holdings Securities Litigation(2020); City of Edinburgh Council v. Pfizer(2014) | Circuit split on core operations doctrine – more restrictive than some circuits but accepts it in narrow circumstances. |

| Fourth Circuit | Requires “strong inference”with particular emphasis on contemporaneous evidence. Skeptical of pure motive and opportunity allegations. | Teachers’ Retirement System v. Hunter(2019); Cozzarelli v. Inspire Pharmaceuticals(2008) | More demanding standard for motive and opportunityallegations compared to First and Ninth Circuits. |

| Fifth Circuit | Applies strict “strong inference”standard. Requires particularized fact ssuggesting deliberate recklessness or actual knowledge. | ABC Arbitrage Plaintiffs Group v. Tchuruk(2002); Rosenzweig v. Azurix Corp.(2003) | Most restrictive circuit on scienter pleading. Rarely accepts motive and opportunity alone. |

| Sixth Circuit | Follows Tellabs with moderate application. Accepts core operations doctrine and strong circumstantial evidence. | In re Omnicare Securities Litigation(2014); Helwig v. Vencor(2001) | Middle ground approach – less restrictive than Fifth Circuit but more demanding than Ninth Circuit. |

| Seventh Circuit | Home of Tellabs decision. Requires holistic analysis where inference of scienter must be at least as compelling as competing inferences. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights(2007); Higginbotham v. Baxter International(2007) | Authoritative circuitpost-Tellabs. Emphasizes comparative plausibility standard. |

| Eighth Circuit | Applies “strong inference”standard with acceptance of core operations doctrine. Moderate approach to motive and opportunity. | In re K-tel International Securities Litigation(2002); In re Navarre Corp. Securities Litigation(2002) | Generally follows mainstream approach without significant departures from other circuits. |

| Ninth Circuit | Most lenient circuit on scienter pleading. Readily accepts motive and opportunity allegations and core operations doctrine. | In re Oracle Corp. Securities Litigation(2010); Zucco Partners v. Digimarc Corp.(2009) | Major circuit split- significantly more plaintiff-friendly than Fifth, Second, and Fourth Circuits. |

| Tenth Circuit | Requires “strong inference”with emphasis on deliberate recklessness. Moderate acceptance of circumstantial evidence. | City of Philadelphia v. Fleming Cos.(2001); Adams v. Kinder-Morgan(2003) | Follows mainstream approach similar to Sixth and Eighth Circuits. |

| Eleventh Circuit | Applies strict “strong inference”standard. Requires particularized allegations of actual knowledge or deliberate recklessness. | Bryant v. Avado Brands(1999); In re Stac Electronics Securities Litigation(1999) | Restrictive approach similar to Fifth Circuit. Skeptical of pure motive and opportunity theories. |

| D.C. Circuit | Follows Tellabs standard with rigorous analysis. Emphasizes need for contemporaneous evidence of scienter. | Jaffee v. Crane Co.(2016); Longman v. Food Lion(1999) | Sophisticated analysis reflecting complex securities cases. Generally restrictive but fact-specific. |

| Federal Circuit | Limited securities jurisdiction. When applicable, follows Tellabs standard with emphasis on technical complexity considerations. | In re Seagate Technology Securities Litigation(2008) | Rarely handles securities cases. Defers to regional circuits on most scienter issues. |

Class Certification: Building the Foundation for Recovery

- Class certification transforms individual investor complaints into powerful collective actions capable of challenging even the largest corporations. During this stage, courts evaluate whether the proposed class meets specific legal requirements: numerosity (enough affected investors to make individual suits impractical), commonality (shared legal or factual questions), typicality (representative plaintiffs’ claims are typical of the class), and adequacy (representatives will fairly protect class interests).

- The certification process has become increasingly sophisticated, with courts demanding detailed economic analysis demonstrating that common issues predominate over individual questions. Successful certification often prompts settlement discussions, as defendants recognize the substantially increased stakes of facing thousands of plaintiffs simultaneously.

Meeting Rule 23(b)(3) Requirements in Securities Class Actions

Securities class actions must clear Rule 23(a) prerequisites and Rule 23(b)(3) requirements. These create additional hurdles for plaintiffs who want certification.

Predominance: Proving Common Issues Outweigh Individual Ones

- Rule 23(b)(3) requires plaintiffs to show that “questions of law or fact common to class members predominate over any questions affecting only individual members”. Courts need to take a “close look” at this requirement, which demands more than just commonality. The courts must analyze claim elements and defenses, look at evidence, and predict how specific issues will unfold.

The fraud-on-the-market theory often determines predominance in securities fraud litigation. This theory creates a reliance presumption for securities traded in efficient markets. Individual damage calculations usually don’t stop certification. However, the Ninth Circuit’s recent ruling in Bowerman v. Field Asset Services, Inc. found class certification might not work when individual inquiries determine if damages exist, rather than just calculating them.

Superiority: Why Class Action Is the Preferred Legal Mechanism

- The second part of Rule 23(b)(3) states that “a class action is superior to other available methods for fairly and efficiently adjudicating the controversy”. Courts look at four key factors:

- Class members’ interests in controlling separate actions

- Extent of existing litigation on the controversy

- Desirability of concentrating claims in the particular forum

- Likely difficulties in managing the class action

- Class actions that meet superiority requirements will save time, effort, and money while promoting uniform decisions. The superiority might not exist when state laws vary widely or when cases need many individual inquiries.

Ascertainability: Ensuring the Class Can Be Clearly Defined

- Courts recognize ascertainability as an implicit requirement for class certification, though Rule 23 does not mention it directly. Circuit courts disagree on how to apply it. The Third Circuit wants a “reliable, administratively feasible” way to identify class members. The Second, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Circuits just ask for objective criteria that set clear membership boundaries. The Second Circuit made it clear that “identifiable does not mean identified; ascertainability does not require a complete list of class members at the certification stage“

- Lead plaintiffs take on big responsibilities. They must stay involved in the legal process, work together with attorneys, and show up for court proceedings. They also need to assess settlement offers. Their choices will affect all class members, which makes picking them a vital part of the process.

Discovery: Uncovering the Evidence

- The discovery phase represents the most intensive and expensive portion of securities litigation, where both sides gather evidence to support their positions. This process typically involves reviewing millions of documents, conducting dozens of depositions, and retaining expert witnesses to analyze complex financial data.

- Modern discovery in securities cases increasingly relies on advanced technology to process vast quantities of electronic communications. Email archives, instant messages, recorded phone calls, and internal presentations often provide the most compelling evidence of fraudulent intent.

- In one recent case involving a major technology company, discovery revealed over 2.3 million relevant documents, including internal emails where executives explicitly discussed manipulating earnings guidance to meet analyst expectations.

- The discovery process also includes extensive fact witness depositions, where current and former employees provide sworn testimony about their knowledge of the alleged misconduct. These depositions frequently produce dramatic revelations, as witnesses describe pressure from senior management to manipulate financial results or conceal material information from investors.

Summary Judgment: The Final Pre-Trial Decision Point

- Summary judgment motions allow either party to argue that no genuine factual disputes exist and that they should prevail as a matter of law. For defendants, successful summary judgment motions can eliminate the case entirely without the expense and uncertainty of trial. For plaintiffs, partial summary judgment on key issues like materiality or loss causation can strengthen their position in settlement negotiations.

- Courts grant summary judgment sparingly in securities cases, recognizing that questions of intent and materiality typically require jury consideration. However, when granted, these rulings often prove dispositive, either eliminating the case entirely or creating such strong precedent that settlement becomes inevitable.

Settlement Negotiations: The Path Most Traveled

- Settlement negotiations occur throughout the litigation process but intensify significantly after class certification and during discovery. Approximately 95% of securities class actions resolve through settlement rather than trial, making these negotiations the most likely path to investor recovery.

- Settlement amounts vary dramatically based on several factors: the size of investor losses, the strength of the legal claims, the defendants’ financial resources, and the availability of insurance coverage. Recent settlements have ranged from $10 million for smaller cases to over $3 billion for the most significant frauds.

- The negotiation process typically involves multiple rounds of discussions, often facilitated by experienced mediators who understand both the legal and business considerations driving each party’s position. Defendants must balance the certainty of settlement against the possibility of trial victory, while plaintiffs evaluate guaranteed recovery against the potential for larger damages if they prevail at trial.

Trial: The Ultimate Resolution

- When cases proceed to trial, the stakes reach their maximum level. Securities trials typically last several weeks and involve complex testimony from fact witnesses, expert economists, and accounting professionals. Juries must navigate sophisticated financial concepts while determining whether defendants committed fraud and, if so, what damages investors suffered as a result.

- Recent trial outcomes demonstrate the high stakes involved. In 2023, a major pharmaceutical company faced a jury verdict exceeding $500 million after trial testimony revealed systematic manipulation of clinical trial data. Conversely, other defendants have achieved complete trial victories, eliminating billions of dollars in potential liability.

Notice to Class Members: Ensuring Fair Representation

- Notice to class members serves the critical function of informing affected investors about the litigation and their rights within the class action framework. Courts require that notice be designed to reach the broadest possible audience of affected investors through multiple channels: direct mail to known shareholders, publication in financial newspapers, and posting on dedicated case websites.

- The notice process has evolved significantly with technological advances. Modern notice programs utilize sophisticated databases to identify institutional investors, employ targeted digital advertising to reach individual shareholders, and provide multilingual materials to ensure broad accessibility.

Final Approval Process: Completing the Recovery

- The final approval process represents the culmination of years of litigation, where courts evaluate whether proposed settlements are fair, reasonable, and adequate for the class. This process includes a fairness hearing where class members can object to the settlement terms or the attorneys’ fee award.

- Courts scrutinize multiple factors during final approval: the strength of the plaintiffs’ case, the amount of the settlement relative to potential damages, the defendants’ ability to pay larger amounts, and the risks of continued litigation. The approval process typically takes several months, after which distribution to class members can begin.

Landmark Cases That Shaped Securities Litigation

The Enron Scandal: A Watershed Moment

Enron

- The Enron scandal remains the quintessential example of how omissions in financial statements can devastate markets and investors.

- The energy company employed sophisticated accounting fraud schemes, including the use of special purpose entities (SPEs) to hide over $1 billion in debt from its balance sheets.

- These corporate scandals involved deliberate omissions of critical financial information that painted a false picture of the company’s financial health.

- Key Legal Precedents Established:

- Enhanced auditor independence requirements under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

- Stricter CEO and CFO certification of financial statements

- Whistleblower protection provisions that encouraged internal reporting of fraud

- The securities litigation that followed resulted in one of the largest bankruptcy proceedings in U.S. history, with investors losing approximately $74 billion in market value.

- The case established crucial precedents for regulatory compliance, particularly regarding the disclosure of off-balance-sheet transactions and the independence of external auditors.

Waste Management

- Waste Management’s senior executives carried out the scheme through a series of fraudulent accounting manipulations.

- The specific mechanisms of the fraud included:

- Manipulated depreciation: Executives repeatedly extended the useful life of company assets, such as garbage trucks, and assigned arbitrary, excessive salvage values to them. This dramatically reduced the annual depreciation expense and artificially boosted profits.

- Improper capitalization of expenses: Maintenance and repair costs for landfills were improperly classified as capital expenses rather than as current-period expenses. This illegally deferred recognition of these costs, making short-term profits appear larger.

- Concealment through “netting”: Management secretly used one-time gains from asset sales to erase unrelated operating expenses and accounting misstatements. This practice, known as “netting,” concealed the true financial health of the company from investors and auditors.

- Inflated environmental reserves: Executives would intentionally inflate environmental liability reserves during strong financial quarters. Then, during weaker quarters, they would release the excess reserves into earnings to boost results.

- Failure to write off impaired assets: The company neglected to write off the costs of abandoned or impaired landfill projects, instead keeping the costs on the balance sheet to hide their negative financial impact.

The role of Arthur Andersen

- Waste Management’s longtime auditor, Arthur Andersen, was complicit in the fraud.

- The audit firm was aware of Waste Management’s improper accounting practices and documented numerous issues, but it repeatedly approved the company’s financial statements with an “unqualified” or “clean” opinion.

- The relationship was tainted by a conflict of interest. Many of Waste Management’s top financial officers were former Arthur Andersen employees, and Andersen was highly protective of the lucrative relationship with its “crown jewel” client.

- Andersen also received substantial fees for non-audit consulting services, which compromised its independence.

Unraveling and consequences

- Discovery: The scheme was discovered in 1997 after a new CEO took over and ordered a review of the company’s accounting practices. He resigned months later after calling the accounting “spooky”.

- Financial restatement: In 1998, Waste Management announced it would restate its earnings from 1992 through 1997, revealing over $1.7 billion in overstated profits.

- Regulatory action: The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) charged Waste Management’s founder and five other top executives with perpetrating the fraud.

- Executives were fired and faced charges of securities fraud. The SEC also fined Arthur Andersen $7 million for its role.

- Stock price collapse: When the fraud was revealed, the company’s stock price plummeted, causing over $6 billion in losses for shareholders.

- Company restructure: Crippled by the scandal, Waste Management was acquired by a smaller competitor, USA Waste Services. The newly merged company kept the Waste Management name but relocated its headquarters and replaced nearly all top executives.

- Legacy for auditors: The scandal was a major contributing factor to the downfall of Arthur Andersen, which was also implicated in the Enron scandal just a few years later.

- Broader reforms: The Waste Management case, alongside other major financial scandals, helped trigger the push for stricter regulations in corporate governance and financial reporting, ultimately leading to the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002.

HealthSouth

- The fraud: The healthcare company HealthSouth, led by CEO Richard Scrushy, was caught in an accounting scandal involving the fraudulent inflation of its earnings. Between 1996 and 2002, the company systematically overstated its profits by billions of dollars to meet analyst expectations.

- The cover-up: The fraud was carried out by executives who would meet to “fill the gap” between actual and reported earnings. The scheme involved falsifying financial records to inflate revenue and hide expenses.

The outcome: When the fraud was uncovered, it led to massive financial restatements, the resignation and eventual conviction of several executives, and a steep drop in the company’s stock price. Although Scrushy was initially acquitted of accounting fraud, he was later convicted of bribery in a separate case.

Recent Tech Company Lawsuits: Modern Challenges

Recent tech company lawsuits demonstrate how securities litigation has evolved to address contemporary business models and disclosure challenges. These cases often involve allegations that companies misrepresented their user metrics, data privacy practices, or artificial intelligence capabilities.

Recent Tech Settlements Include:

- Apple: $490 million. This settlement addressed allegations related to CEO Tim Cook’s statements about iPhone sales in China in 2018.’

- Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.: $433.5 million.

- VMware, Inc.: $102.5 million. This settlement is pending final court approval.

- TuSimple Holdings: $189 million

Regulatory Framework: The Enforcement Ecosystem

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC): The Primary Regulator

- The SEC serves as the primary federal regulator responsible for enforcing securities laws and protecting investors. The Commission’s enforcement division investigates potential violations, brings civil enforcement actions, and works closely with criminal prosecutors when cases involve intentional fraud.

- SEC investigation procedures have become increasingly sophisticated, utilizing advanced data analytics to identify potential misconduct patterns. The Commission’s examination staff conducts routine inspections of investment advisers, broker-dealers, and other regulated entities, while the enforcement division focuses on investigating specific violations.

- Recent SEC enforcement statistics demonstrate the agency’s aggressive approach to securities violations. In fiscal year 2023, the Commission filed 784 enforcement actions and obtained $4.95 billion in monetary remedies. These actions included cases against public companies, investment advisers, broker-dealers, and individual executives.

- Total Enforcement Actions: 784, with 501 being “stand-alone” actions covering a range of violations.

- Monetary Remedies: $4.95 billion was obtained, including $3.369 billion in disgorgement and prejudgment interest, and $1.580 billion in civil penalties.

- Officer and Director Bars: The SEC obtained 133 officer and director bars, the highest number in a decade.

- Investor Distributions: $930 million was distributed to harmed investors.

Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA): Self-Regulation in Action

- The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) operates as the primary self-regulatory organization for the securities industry, overseeing broker-dealers and their registered representatives. The organization’s enforcement program focuses on sales practice violations, market manipulation, and failures to supervise registered personnel.

- FINRA’s disciplinary actions often precede or complement SEC enforcement efforts. The organization’s arbitration system also provides an alternative dispute resolution mechanism for investor complaints against broker-dealers, handling over 3,000 cases annually with total awards exceeding $100 million.

FINRA v. AAG Capital (May 2025)

- FINRA fined and censured the firm AAG Capital in May 2025 over unsuitable variable annuity recommendations.

- Settlement details: AAG Capital agreed to pay $138,591 in fines and restitution.

- Violations: FINRA found that between February 2021 and April 2023, the firm made 479 RILA transactions totaling over $92 million, with some exchanges resulting in additional fees for customers. The recommendations did not meet the standards required by Regulation Best Interest (Reg BI).

- Supervisory failures: The firm failed to maintain adequate policies and supervisory procedures tailored to the complexities of RILA products, which are sensitive to market index performance.

- Other recent enforcement actions demonstrate FINRA’s broader crackdown on firms that fail to adequately supervise representatives selling complex products:

- Options trading (August 2025): In August 2025, FINRA fined Interactive Brokers $650,000 for failing to properly supervise options trading activity by customers. The automated systems used to approve customers for higher-risk activities were deemed insufficient.

- Alternative investments (January 2025): In January 2025, a firm and its sole principal were sanctioned for failing to supervise the suitability of a trading strategy involving a high-risk Exchange Traded Note (ETN). The firm had inadequate policies for analyzing the product’s suitability and evaluating customer concentration.

- L-Share annuities (February 2025): In a separate action involving variable annuities, multiple firms were fined and ordered to pay restitution for improperly recommending L-share annuities to customers with long-term investment goals. L-share products are meant for short-term investors but have higher fees.

- Reg BI failures (March 2025): An enforcement action in March 2025 involved a firm and a representative who were sanctioned for unsuitable recommendations of speculative alternative investments. The representative was required to complete continuing education on Regulation Best Interest.

Department of Justice (DOJ): Criminal Enforcement

Department of Justice (DOJ): Criminal Enforcement

- The Department of Justice (DOJ) brings criminal prosecutions against individuals and entities that commit securities fraud, working closely with the SEC to ensure comprehensive enforcement coverage. Criminal cases require proof beyond a reasonable doubt, a higher standard than civil cases, but can result in imprisonment and substantial fines.

- Recent DOJ prosecutions have targeted corporate executives who engaged in accounting fraud, insider trading, and market manipulation. The department’s Corporate Crime Advisory Group coordinates complex investigations involving multiple agencies and jurisdictions.

- The former chairman and Chief Executive Officer of FTE Networks, Inc. (“FTE”), was sentenced today to 12 years in prison by U.S. District Judge Colleen McMahon for leading a years-long scheme to inflate FTE’s revenue, conceal liabilities and expenses, and embezzle company funds. The defendant previously pled guilty in August 2023 to conspiring to commit securities and wire fraud, making false statements in SEC filings and improperly influencing the conduct of audits, securities fraud, wire fraud, and aggravated identity theft.

Emerging Trends and Future Challenges

- The landscape of securities litigation continues evolving rapidly, driven by technological advances, changing business models, and increased regulatory scrutiny. Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications are creating new disclosure obligations and potential liability theories, while cryptocurrency and digital assets present novel legal challenges.

- Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosures represent a growing area of securities litigation risk. Companies face increasing pressure to provide detailed information about their environmental impact, social responsibility initiatives, and governance practices. Misstatements or omissions in these areas can trigger securities fraud claims, particularly as ESG considerations become more central to investment decisions.

- Cybersecurity disclosures present another emerging challenge. Companies must balance transparency about cyber threats and incidents with concerns about revealing vulnerabilities to potential attackers. Recent enforcement actions suggest that both inadequate disclosure and delayed reporting of material cybersecurity incidents can trigger securities violations.

- The integration of advanced analytics and artificial intelligence into fraud detection promises to transform both enforcement and defense strategies. Regulators increasingly use sophisticated algorithms to identify suspicious trading patterns and accounting anomalies, while defendants employ similar technologies to analyze vast document collections during discovery.

Protecting Investors: Practical Guidance

Protecting Investors: Practical Guidance

For investors seeking to protect themselves from securities fraud, understanding common warning signs remains crucial. Red flags include: management teams with histories of regulatory violations, frequent changes in auditors or key financial personnel, unusual related-party transactions, and financial results that consistently exceed industry benchmarks without clear explanations.

Due diligence should extend beyond reviewing public filings to include analysis of management credibility, competitive positioning, and industry trends. Investors should maintain healthy skepticism when companies report results that seem too good to be true or inconsistent with broader economic conditions.

Diversification remains the most effective protection against individual company fraud. Even sophisticated investors with extensive due diligence capabilities cannot eliminate the risk of corporate misconduct entirely. Spreading investments across multiple companies, industries, and asset classes reduces the impact of any single fraud on overall portfolio performance.

When fraud does occur, affected investors should act quickly to preserve their rights. Securities class actions typically have strict deadlines for participation, and early involvement can influence case strategy and settlement negotiations. Consulting with experienced securities litigation attorneys helps ensure that investors understand their options and make informed decisions about participation.

The future of securities litigation will likely involve continued evolution in response to technological advances, changing business models, and regulatory developments. As financial markets become increasingly complex and interconnected, the role of securities litigation in maintaining market integrity and protecting investor interests becomes ever more critical.

Investors who stay informed about these developments, maintain appropriate skepticism about investment opportunities, and understand their legal rights when fraud occurs will be best positioned to navigate the challenges and opportunities of modern financial markets. The intersection of law, finance, and technology ensures that securities

Contact Timothy L. Miles Today for a Free Case Evaluation

If you suffered substantial losses and wish to serve as lead plaintiff in a securities class action, or have questions about securities class action settlements, or just general questions about your rights as a shareholder, please contact attorney Timothy L. Miles of the Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles, at no cost, by calling 855/846-6529 or via e-mail at [email protected]. (24/7/365).

Timothy L. Miles, Esq.

Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles

Tapestry at Brentwood Town Center

300 Centerview Dr. #247

Mailbox #1091

Brentwood,TN 37027

Phone: (855) Tim-MLaw (855-846-6529)

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.classactionlawyertn.com

Facebook Linkedin Pinterest youtube

Visit Our Extensive Investor Hub: Learning for Informed Investors