Intruction and Summary to Securities Fraud and Securities Litigation

- Securities Fraud and Securities Litigation: Securities fraud is the deliberate misrepresenting of financial statements which triggers securites litigations to recover investor losses.

- Securities fraud: Is deceptive conduct, like misrepresenting facts or omitting crucial information, in the sale of a security that causes financial loss to investors.

- Legal Process: Securities litigation is the legal process used to resolve disputes arising from securities fraud and other forms of corporate misconduct, such as insider trading, market manipulation, and breaches of fiduciary duties.

- Purpose: The purpose of securities litigation is to protect investors, ensure market fairness, and hold companies and individuals accountable for financial wrongdoing.

Securities Fraud

- Definition: Fraudulent actions in connection with the offer and sale of a security.

- Key Elements:

- Material Misrepresentation: A false statement that is important to investors and likely to affect the stock price.

- Material Omission: The failure to disclose crucial information that, if known, would have influenced an investor’s decision, such as a government investigation.

- Material Misrepresentation: A false statement that is important to investors and likely to affect the stock price.

- Examples:

- Providing an overly positive, yet false, picture of a company’s finances to attract investors.

- Failing to disclose important information, such as an ongoing government investigation, which could affect stock value.

- Providing an overly positive, yet false, picture of a company’s finances to attract investors.

- Consequences: Investors must have suffered financial damages to bring a case.

Securities Litigation

- Purpose:To safeguard investors from deceit, ensure transparency, and promote accountability within the financial markets.

- Common Forms:

- Securities Fraud Class Actions:A lawsuit brought by a large group of investors who were all harmed by the same fraudulent conduct.

- Shareholder Derivative Actions:Lawsuits filed by shareholders on behalf of the corporation against its directors or officers, often for breaches of fiduciary duty.

- Market Manipulation Cases:Legal actions addressing the artificial inflation or deflation of stock prices to deceive investors.

- Securities Fraud Class Actions:A lawsuit brought by a large group of investors who were all harmed by the same fraudulent conduct.

- Key Players:

- Regulatory Bodies:Agencies like the SEC play a crucial role in enforcing securities laws and protecting investors.

- Lawyers:Securities litigators represent both companies and individuals in federal and state court, as well as in regulatory investigations.

- Regulatory Bodies:Agencies like the SEC play a crucial role in enforcing securities laws and protecting investors.

- Outcomes:The goal is often to achieve financial restitution for harmed investors or to force changes in corporate behavior and governance.

- Material misrepresentation or omission: The defendant made a false statement or failed to disclose a fact that a reasonable investor would have considered important.

- Scienter: The defendant acted with intent to deceive or with “reckless disregard” for the truth.

- Causation: The misrepresentation or omission caused the plaintiff to buy or sell the security.

- Reliance: The plaintiff relied on the misrepresentation when making their investment decision.

- Economic loss: The plaintiff suffered a financial loss as a direct result of the fraud.

The consequences of securities fraud

- Criminal prosecution: The Department of Justice may bring criminal charges, which can result in long prison sentences and millions of dollars in fines.

- Civil penalties: The SEC can impose substantial civil fines and require the violator to return profits to investors.

- Private lawsuits: Investors can recover their financial losses through settlements or damage awards from civil lawsuits.

- Harm to reputation: Beyond legal penalties, companies and individuals face severe reputational damage that can erode public trust and have lasting business consequences

Understanding Securities Fraud: Definition and Types

- Securities fraud: Refers to a range of deceptive practices in the stock and commodities markets. These practices often involve misrepresentation of information that investors use to make decisions. Fraud can take many forms and is typically aimed at manipulating the market or deceiving investors into making financial decisions that are not in their best interest.

- Core Principles: The core of securities fraud lies in the violation of trust that is central to the functioning of financial markets. It undermines the confidence investors have in the market, which can have significant consequences for both individual portfolios and the economy at large.

- Statistics: Recent statistics from the SEC Enforcement division reveal it recovered $8.2 billion in financial remedies in 2024, the highest annual recovery in SEC history .

Types of Securities Fraud

- Insider Trading: One prevalent type of securities fraud is insider trading, where individuals with non-public, material information about a company buy or sell stocks in violation of their duty to the company and its shareholders.

- Ponzi Schemes: Another common form is accounting fraud, where a company intentionally misstates its financial condition, usually to inflate stock prices. Ponzi schemes, which promise high returns with little risk to investors and pay earlier investors with the capital from newer ones, also fall under securities fraud. These are just a few examples of how securities fraud can manifest, each with unique characteristics but similar in their intent to deceive and defraud investors.

- Complexity: The complexity of securities fraud is further compounded by the various methods perpetrators use to conceal their actions. Technological advancements have introduced new challenges, as fraudsters exploit digital platforms to commit or facilitate fraudulent activities.

- Technology: This evolution necessitates a continuous update in detection and prevention strategies. Understanding the types of securities fraud is the first step in recognizing and combating these illicit activities. It is crucial for investors to be aware of these tactics to better protect their investments and ensure they are making decisions based on truthful and transparent information.

TYPES OF SECURITES FRAUD

Fraud Type | Description |

| Affinity Fraud | Scammers target members of specific groups—like religious or ethnic communities—and exploit their trust to sell them fraudulent investments. |

| Boiler Rooms | A common tactic where salespeople use high-pressure sales tactics, often over the phone, to sell bogus investments or inflated stocks to unsuspecting investors. |

| Embezzlement | A broker or financial manager pockets client funds instead of investing them as promised, and tells the client the assets were lost in the market. |

| Insider Trading | Trading securities based on material, non-public information about a company. |

| Misleading Financial Statements | Companies or individuals manipulate financial reports to present a false picture of financial health, often to attract investors or inflate stock prices. |

| Ponzi Schemes | A fraudulent investment operation where the operator pays returns to earlier investors using capital from more recent investors. |

| Pump and Dump Schemes | Fraudsters inflate the price of a stock through false and misleading positive statements, then sell their shares, causing the price to fall and other investors to lose money. |

| Pyramid Schemes | Similar to Ponzi schemes, but with a strong emphasis on recruiting new members to generate money for existing ones. |

| Recovery Room Schemes | Scammers promise to help victims recover money lost in previous scams, but require up-front payments to fund the recovery, only to disappear with the funds. |

| Unsuitable Investments | Financial advisors may recommend or sell financial products that are not appropriate for the investor’s risk tolerance or financial situation, but earn the advisor a higher commission. |

Recent High-Profile Cases and Their Impact

High-profile cases

- Change Healthcare Ransomware Attack (2024): In one of the largest healthcare-related ransomware incidents ever, an attack on Change Healthcare exposed the data of at least 100 million Americans. The fallout caused widespread payment disruptions for healthcare providers and pharmacies.

- CDK Global Ransomware Attack (2024): The BlackSuit ransomware group disrupted thousands of car dealerships across the U.S. and Canada, causing significant financial losses for CDK Global and disrupting vehicle sales.

- MoveIT Data Breach (2023): A vulnerability in the MoveIT file transfer software was exploited by the Clop cybercriminal group, affecting over 2,500 organizations and exposing the sensitive personal data of tens of millions of individuals.

- MGM Resorts and Caesars Entertainment Ransomware Attacks (2023): These separate, high-profile attacks by the Scattered Spider group hobbled casino and hotel operations in Las Vegas and resulted in major financial and reputational damage.

Key impacts

- Systemic vulnerabilities: The attacks exposed major flaws in interconnected systems, from healthcare payments to corporate supply chains, demonstrating how a single point of failure can trigger cascading failures across an industry.

- Evolving cyber warfare: Nations and state-sponsored groups are increasingly using cyberattacks to sow chaos and gather intelligence, with cases like the U.S. telecommunications hack in 2024 revealing sophisticated espionage campaigns.

- Third-party risk: Many breaches occurred through vulnerabilities in third-party vendors, highlighting the need for companies to assess the security of their entire supply chain, not just their internal systems.

- Increased financial risk and legal action: Companies face massive recovery costs, regulatory fines, and class-action lawsuits. The attacks have also driven up the cost and tightened the availability of cybersecurity insurance.

Artificial intelligence (AI)

- The rapid adoption of generative AI has produced a wave of high-profile legal challenges, primarily focusing on copyright infringement and ethical concerns.

High-profile cases

- Bartz v. Anthropic (2024–2025): In a landmark copyright case, a federal judge ruled that while using copyrighted material for AI model training may be fair use, illegally acquiring that content is not. The case was later settled for $1.5 billion, the largest-ever copyright recovery.

- The New York Times v. OpenAI and Microsoft (2023): The New York Times sued OpenAI and Microsoft, alleging copyright infringement for using its content without permission to train generative AI models and produce output that competes with its journalism. The lawsuit was folded into a larger multi-district litigation in April 2024.

- Getty Images v. Stability AI (2023): The photo agency sued the AI art generator for using its copyrighted images to train the Stable Diffusion model. This case ttests the limits of fair use for image-generating AI.

- Dow Jones & Co. v. Perplexity AI (2024): Dow Jones sued Perplexity, claiming the AI startup illegally copied its news content for its “skip the links” feature, which bypasses original publishers and diverts web traffic.

Key impacts

- Re-evaluation of copyright: These cases are forcing a re-evaluation of fair use in the context of AI. The outcomes may accelerate the growth of a data licensing market, where AI companies must pay for training data.

- Liability and safety: The growing “agentic era” of AI raises new questions about legal liability when an AI agent makes a mistake. Lawsuits like those against Character.AI highlight the need for “trust and safety” protocols and liability considerations.

- Defining human creativity: Court rulings, such as Thaler v. Perlmutter, affirming that human authorship is required for copyright protection, are defining the intersection of AI and human creativity.

- Regulatory uncertainty: A lack of clear federal regulation has led to increased state-level scrutiny of AI, particularly in sensitive sectors like employment and healthcare. Lawmakers and regulators are using these cases to inform new legislation.

TYPES OF DATA TARGETED BY CYBERCRIMINALS

Type of Data | Why It’s Targeted | Examples of Misuse |

Business Correspondence | Used for social engineering, blackmail, or sabotage | “Spear-phishing,” CEO fraud, leaking sensitive negotiations |

Cloud-stored Data | Exploited due to insufficient protection in shared environments | Data destruction, unauthorized access to customer accounts |

| Credentials | Enables unauthorized access to systems or accounts | “Credential stuffing,” account hijacking, further breaches |

Customer Data | Exploited to compromise trust or for phishing scams | Tailored phishing attacks, spam campaigns, reputation damage |

Financial Information | To gain money immediately or sell on the dark web | Unauthorized transactions, account takeovers, financial fraud |

| Government Data | Compromises national security or supports espionage | Espionage, diplomatic scandals, economic sabotage |

Health Records | High value on black markets; exploitation of vulnerabilities | Insurance fraud, blackmail, fake prescription claims |

Intellectual Property | Gives competitors or attackers an economic advantage | Theft of trade secrets, technology blueprints, exploiting firms’ research and development |

| Login and Password Data | Foundation for further attacks or resale | Credential stuffing, ransomware deployment, insider threats |

Operational Data | Targets infrastructure to disrupt business activities | Industrial sabotage, ransomware attacks on supply chains |

| Payment Information | Quick financial gain through carding or fraud | Credit card fraud, illicit transactions, resale on black markets |

Personal Identifiable Information | Used for identity theft, fraud, and social engineering | Fraudulent loans, tax fraud, fake identities for crimes |

The Impact of Securities Fraud on Investors and Markets

Impact

- Effects: The effects of securities fraud on investors and financial markets can be devastating. For individual investors, the immediate impact is often financial loss.

- False Information: When investors make decisions based on false or misleading information, they may buy overpriced stocks or sell undervalued ones, leading to significant financial setbacks. Beyond the direct financial loss, securities fraud erodes investor confidence.

- Trust in Market: When trust in the market’s integrity is undermined, investors may become more hesitant to engage, which can reduce market liquidity and overall participation.

Recovery Mechanism:

- Securities class actions have become the primary mechanism through which investors seek recovery for losses caused by corporate fraud.

- In 2024, the average settlement amount in securities class action lawsuits was approximately $42.4 million. The 2015-2023 average settlement amount was $50.7 million.

- The securities litigation process typically involves extensive discovery, expert testimony, and complex damages calculations that can take years to resolve.

THE SECURITIES LITIGATION PROCEESS

| Filing the Complaint | A lead plaintiff files a lawsuit on behalf of similarly affected shareholders, detailing the allegations against the company. |

| Motion to Dismiss | Defendants typically file a motion to dismiss, arguing that the complaint lacks sufficient claims. |

| Discovery | If the motion to dismiss is denied, both parties gather evidence, documents, emails, and witness testimonies. This phase can be extensive. |

| Motion for Class Certification | Plaintiffs request that the court to certify the lawsuit as a class action. The court assesses factors like the number of plaintiffs, commonality of claims, typicality of claims, and the adequacy of the proposed class representation. |

| Summary Judgment and Trial | Once the class is certified, the parties may file motions for summary judgment. If the case is not settled, it proceeds to trial, which is rare for securities class actions. |

| Settlement Negotiations and Approval | Most cases are resolved through settlements, negotiated between the parties, often with the help of a mediator. The court must review and grant preliminary approval to ensure the settlement is fair, adequate, and reasonable. |

| Class Notice | If the court grants preliminary approval, notice of the settlement is sent to all class members, often by mail, informing them about the terms and how to file a claim. |

| Final Approval Hearing | The court conducts a final hearing to review any objections and grant final approval of the settlement. |

| Claims Administration and Distribution | A court-appointed claims administrator manages the process of sending notices, processing claims from eligible class members, and distributing the settlement funds. The distribution is typically on a pro-rata basis based on recognized losses. |

The Heighened Pleadings Standards Under the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995

- The Game Changer: The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (PSLRA) introduced heightened pleading standards in securities fraud cases, requiring plaintiffs to specify the allegedly misleading statements, explain why they were misleading, and state with particularity the facts supporting such claims, especially those made on information and belief. Crucially, plaintiffs must also plead with particularity facts giving rise to a “strong inference” that the defendant acted with scienter (fraudulent intent).

- Raising the Bar: This higher bar was intended to deter frivolous “strike suits” that injured the economy, though it has been criticized for potentially preventing some meritorious claims from succeeding.

PRE- AND POST-PSLRA STANDARDS FOR SECURITIES FRAUD LITIGATION

Feature | Pre-PSLRA Standard | Post-PSLRA Standard |

Motion to dismiss | Based on “notice pleading” (Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(a)), making it easier for plaintiffs to survive motions to dismiss. This often led to settlements to avoid costly litigation. | Requires satisfying PSLRA’s heightened pleading standards and the “plausibility” standard from Twombly and Iqbal. Failure to plead with particularity on any element can result in dismissal. |

Pleading | “Notice pleading” was generally sufficient, though fraud claims under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b) required particularity for the circumstances of fraud, but intent could be alleged generally. | Each misleading statement must be stated with particularity, explaining why it was misleading. Facts supporting beliefs in claims based on “information and belief” must also be stated with particularity. |

| Scienter | Pleaded broadly; the “motive and opportunity” test was often sufficient to infer intent. | Requires alleging facts creating a “strong inference” of fraudulent intent, which must be at least as compelling as any opposing inference of non-fraudulent intent, as clarified in Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd.. |

| Loss causation | Not a significant pleading hurdle, often assumed if a plaintiff bought at an inflated price. | Requires pleading facts showing the fraud caused the economic loss, often by linking a corrective disclosure to a stock price drop. Dura Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Broudo affirmed this. |

| Discovery | Could proceed while a motion to dismiss was pending. | Automatically stayed during a motion to dismiss. |

Safe harbor for forward-looking statements | No statutory protection. | Protects certain forward-looking statements if accompanied by “meaningful cautionary statements”. |

Lead plaintiff selection | Often the first investor to file. | Court selects based on a “rebuttable presumption” that the investor with the largest financial interest is the most adequate. |

Liability standard | For non-knowing violations, liability was joint and several. | For non-knowing violations, liability is proportionate; joint and several liability applies only if a jury finds knowing violation. |

Mandatory sanctions | Available under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11, but judges were often reluctant to impose them. | Requires judges to review for abusive conduct |

Key Elements of the Heightened Pleading Standard

- Particularity of Misleading Statements:Plaintiffs must identify the specific statement alleged to be misleading and eexplain the reasons for that alleged falsity.

- Information and Belief Allegations:When a claim is based on information and belief (information gathered from sources other than personal knowledge), the complaint must state with particularity all the facts on which that belief is based.

- “Strong Inference” defined:The Supreme Court has clarified that a “strong inference” is one that is “cogent and at least as compelling as any opposing inference one could draw from the facts alleged“.

- Recklessness is sufficient:While not codifying the prior “motive and opportunity” test, recklessness on the part of the defendant can be sufficient to satisfy the scienter requirement.

- Automatic Stay of Discovery: The PSLRA imposes an automatic stay on discovery while a motion to dismiss is pending. This was intended to prevent plaintiffs from filing speculative lawsuits and using discovery to force settlements.

- Consequences and Impact: The PSLRA’s standards have resulted in more dismissals of securities fraud complaints, particularly those alleging reckless conduct. Some studies indicate that the standards have improved the quality of securities class action cases by

- Consequences and impact. However, the precise application of these requirements remains a subject of ongoing debate and litigation.

CIRCUIT COURT STANDARDS FOR PLEADING LOSS CAUSATION

| Circuit | Summary of pleading standard | Key cases | Notes and circuit splits |

First Circuit | Applies a relatively lenient standard under Rule 8(a), requiring only plausible allegations that connect the corrective disclosure to the preceding misrepresentation. | Massachusetts Retirement Systems v. CVS Caremark Corp. (2013). | Stands with circuits requiring only “plausible” allegations rather than particularity. |

| Second Circuit | Requires plaintiffs to allege that the subject of the fraudulent statement was the cause of the actual loss suffered. Does not require particularized pleading. | Lentell v. Merrill Lynch & Co. (2005); Emergent Capital Inv. Mgmt., LLC v. Stonepath Grp., Inc. (2003). | Focuses on “zone of risk” analysis and requires that the misstatement concerns the very facts that caused the loss. |

Third Circuit | Follows a moderate approach under Rule 8(a), requiring a causal connection between the misrepresentation and the loss that is more than merely possible or speculative. | McCabe v. Ernst & Young, LLP (2007); EP Medsystems, Inc. v. EchoCath, Inc. (2000). | Requires plaintiffs to demonstrate that the revelation of fraudulent information was a “substantial factor” in causing the decline in stock value. |

Fourth Circuit | Applies the heightened Rule 9(b) pleading standard to loss causation, requiring plaintiffs to plead with particularity how the corrective disclosure relates to the prior misrepresentation. | Katyle v. Penn National Gaming, Inc. (2011); Teachers’ Ret. Sys. of LA v. Hunter (2007). | Stands with the Seventh and Ninth Circuits in requiring particularized pleading of loss causation. |

| Fifth Circuit | Requires that plaintiffs allege both that the corrective disclosure specifically revealed the fraud and that the revelation of the fraud caused the loss. | Pub. Emps. Ret. Sys. of Miss. v. Amedisys, Inc. (2014); Lormand v. US Unwired, Inc. (2009). | Particularly stringent about the connection between corrective disclosure and prior misrepresentation. |

Sixth Circuit | Follows a moderate approach, requiring plaintiffs to demonstrate a causal connection between the misrepresentation and the loss, but not requiring the heightened particularity of Rule 9(b). | Ohio Pub. Emps. Ret. Sys. v. Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp. (2016); IBEW Local 58 v. Royal Bank of Scotland (2013). | Focuses on whether the disclosure revealed “some aspect” of the prior misrepresentation. |

| Seventh Circuit | Applies the heightened Rule 9(b) pleading standard to all elements of securities fraud, including loss causation. | Tricontinental Industries v. PricewaterhouseCoopers (2007); Ray v. Citigroup Global Markets (2007). | Stands with the Fourth and Ninth Circuits in requiring particularized pleading of loss causation. |

Eighth Circuit | Applies a relatively lenient standard, requiring only that the complaint provide the defendant with notice of the plaintiff’s claim that the misrepresentation caused the loss. | In re Cerner Corp. Sec. Litig. (2005); Schaaf v. Residential Funding Corp. (2008). | Tends to analyze loss causation under the more permissive Rule 8(a) standard. |

Ninth Circuit | Applies the heightened Rule 9(b) pleading standard to all elements of securities fraud, including loss causation. | Oregon Public Employees Retirement Fund v. Apollo Group Inc. (2014); Metzler Inv. GMBH v. Corinthian Colleges, Inc. (2008). | Previously inconsistent but firmly established Rule 9(b) standard in Oregon Public Employees v. Apollo (2014). |

Tenth Circuit | Applies a moderate approach that requires a logical link between the misrepresentation and the economic loss, but does not explicitly require Rule 9(b) particularity. | In re Williams Sec. Litig. (2007); Nakkhumpun v. Taylor (2015). | Focuses on whether the disclosure revealed “some aspect” of the prior misrepresentation. |

Eleventh Circuit | Requires plaintiffs to plead that the misrepresentation was the “substantial or significant contributing factor” in the loss, but generally follows Rule 8(a). | Hubbard v. BankAtlantic Bancorp, Inc. (2012); FindWhat Investor Group v. FindWhat.com (2011). | Emphasizes proximate causation principles in loss causation analysis. |

D.C. Circuit | Has limited securities fraud jurisprudence but generally follows a more lenient approach aligned with Rule 8(a). | Plumbers & Steamfitters Local 773 Pension Fund v. Danske Bank (2020). | Generally follows the Supreme Court’s guidance in Dura Pharmaceuticals without imposing heightened pleading requirements. |

CIRCUIT COURT STANDARDS FOR PLEADING LOSS CAUSATION

Circuit | Summary of Pleading Standard | Key Cases | Notes and Circuit Splits |

1st Circuit | Holistic approach: Strong inference arises when facts alleged, taken collectively, give rise to a cogent and compelling inference of scienter that is at least as compelling as any opposing inference. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007); In re Cabletron Sys., Inc. (2002) | No major splits. Follows mainstream interpretation requiring inference of scienter to be “at least as strong” as innocent explanations. |

| 2nd Circuit | Comparative approach: Strong inference exists when allegations, taken collectively, give rise to an inference of scienter that is cogent and at least as compelling as any opposing inference one could draw from the facts alleged. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007); ATSI Commc’ns, Inc. v. Shaar Fund, Ltd. (2007) | Leading circuit in securities litigation. Emphasizes collective consideration of all facts rather than piecemeal analysis. |

3rd Circuit | Strong inference standard: Requires cogent and compelling inference from facts alleged, considered holistically, that defendant acted with required state of mind. Motive and opportunity alone insufficient. | In re Advanta Corp. Sec. Litig. (2010); Cal. Pub. Employees’ Ret. Sys. v. Chubb Corp. (2005) | Strict application. Requires more than mere motive and opportunity. Emphasizes contemporaneous evidence of fraudulent intent. |

4th Circuit | Holistic evaluation: Strong inference must be cogent and at least as compelling as any opposing inference. Considers totality of circumstances including timing, motive, and opportunity. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007); Longman v. Food Lion, Inc. (1999) | Moderate approach. Allows consideration of circumstantial evidence but requires substantial factual support. |

| 5th Circuit | Rigorous standard: Strong inference requires allegations that render scienter inference cogent and at least as compelling as competing innocent explanations. High bar for pleading. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007); Rosenzweig v. Azurix Corp. (2003) | Defendant-friendly jurisdiction. Higher pleading threshold than some circuits. Frequently dismisses cases for insufficient scienter allegations. |

6th Circuit | Collective inference approach: Examines all facts alleged collectively to determine whether they give rise to strong inference of scienter that is at least as compelling as innocent explanations. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007); In re Omnicare, Inc. Sec. Litig. (2010) | Balanced approach. Considers corporate culture and systematic misconduct as evidence of scienter. |

| 7th Circuit | Tellabs standard: Strong inference must be more than merely plausible or reasonable—it must be cogent and at least as compelling as any opposing inference. Birthplace of Tellabs decision. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007); Higginbotham v. Baxter Int’l Inc. (2007) | Originating circuit for Tellabs. Strict interpretation requiring inference to be “at least as strong” as innocent explanations. |

| 8th Circuit | Holistic standard: Strong inference arises when collective facts alleged give rise to cogent and compelling inference of scienter that is at least as strong as competing innocent inferences. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007); In re K-tel Int’l, Inc. Sec. Litig. (2002) | Conservative approach. Requires detailed factual allegations beyond conclusory statements about intent. |

9th Circuit | Liberal pleading approach: More plaintiff-friendly interpretation allowing strong inference from circumstantial evidence, timing, and magnitude of alleged fraud. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007); In re Silicon Graphics Inc. Sec. Litig. (1999) | CIRCUIT SPLIT: More plaintiff-friendly than other circuits. Lower threshold for establishing strong inference compared to 2nd, 5th, and 7th Circuits. |

10th Circuit | Moderate standard: Strong inference requires cogent and compelling inference from facts alleged, considered collectively, that is at least as strong as competing innocent explanations. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007); City of Philadelphia v. Fleming Cos. (2001) | Middle-ground approach. Balances plaintiff and defendant interests. Considers industry expertise of defendants. |

| 11th Circuit | Rigorous application: Strong inference must be cogent and at least as compelling as innocent explanations. Emphasizes contemporaneous evidence and rejects hindsight bias. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007); Bryant v. Avado Brands, Inc. (1999) | Strict standard. Rejects hindsight analysis. Requires evidence of fraudulent intent contemporaneous with alleged misconduct. |

D.C. Circuit | Sophisticated analysis: Strong inference requires cogent and compelling inference from well-pleaded facts that is at least as strong as competing innocent inferences. High analytical rigor. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007); Nursing Home Pension Fund v. Oracle Corp. (2004) | Analytically rigorous. Complex fact patterns given careful consideration. Emphasis on regulatory expertise context. |

| Federal Circuit | Limited securities jurisdiction: Applies Tellabs standard in rare securities cases involving patents or government contracts. Defers to regional circuit precedent when possible. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd. (2007) | Minimal securities docket. Defers to regional circuits for securities law interpretation. Specialized jurisdiction focus. |

Materiality

- Definition: Information is material if there is a “substantial likelihood that a reasonable shareholder would consider it important in making an investment decision” or if its disclosure would have significantly altered the “total mix” of information available.

- Objective standard: This standard is objective; it considers how a hypothetical reasonable investor would view the information, not how an individual investor viewed it.

- Challenges: Determining materiality can be complex, and courts have found certain types of information, like general optimistic statements or “puffery,” to be immaterial as a matter of law. However, even quantitatively insignificant information can be qualitatively material if it involves fraud, illegal activities, or other significant issues.

- Trends: In cases involving social media and the use of Section 1348 (Title 18 fraud statutes), prosecutors have sometimes argued for a lower materiality standard, focusing on a statement’s capacity to influence any decision-maker, rather than specifically a “reasonable investor”. However, defense counsel can argue that for securities fraud, the standard should remain the “reasonable investor” regardless of the statute used.

What is the “fraud-on-the-market” theory?

- It’s a legal presumption that allows plaintiffs in securities class actions to satisfy the reliance element of a fraud claim (i.e., that investors actually relied on the fraudulent misstatement when making their investment decision) without having to prove individual reliance for every single class member.

- The underlying assumption: The theory assumes that in an efficient market, all publicly available material information (including fraudulent misrepresentations or omissions) is iimmediately incorporated into the market price of a security. Therefore, investors who trade in reliance on the integrity of the market price are presumed to have indirectly relied on the misrepresentation.

- Origins: The theory was officially endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court in Basic Inc. v. Levinson (1988).

The key “splits” and debates

- Market Efficiency (and rebutting the presumption):

- The Halliburton II Decision (2014): This was a major Supreme Court case that affirmed the fraud-on-the-market theory but clarified how defendants can challenge it. Halliburton II held that defendants could introduce evidence at the class certification stage to rebut the presumption of reliance by demonstrating that the alleged misrepresentation did not affect the stock’s market price. If the misrepresentation had no price impact, then the integrity of the market price was not affected, and thus there’s no common reliance.

- Post-Halliburton II Splits/Debates: While Halliburton II provided clarity, it led to new debates in lower courts about the type and quality of evidence required to prove or disprove price impact at the class certification stage. Some circuits have been more receptive to certain types of event studies or expert testimony than others, and there’s ongoing litigation about the methodological requirements for showing price impact (or lack thereof).

- Example: Debates often revolve around whether an event study showing no price impact on the corrective disclosure date is sufficient, or if courts should consider earlier “inflation-maintaining” misstatements and their initial price impact (or lack thereof).

- Scope of “Efficient Markets”:

- While the theory generally applies to actively traded securities on major exchanges, there can be debates about whether less efficient markets (e.g., smaller companies, certain foreign markets, or specific types of securities) qualify for the presumption. Courts might scrutinize the “efficiency factors” (like trading volume, number of analysts covering the stock, presence of market makers, etc.) more closely in these cases.

- Applying the Theory in Different Contexts (e.g., State vs. Federal Law):

- The fraud-on-the-market theory is primarily a federal securities law construct. While many state securities laws mirror federal law, some states have not explicitly adopted the theory or have different standards for proving reliance. This creates potential “splits” in how reliance is proven if cases are brought under state law.

- “Price Maintenance” vs. “Price Impact”:

- Some litigation has focused on whether a plaintiff must show that the misstatement caused an initial price inflation (meaning the stock price went up due to the lie) or merely maintained an artificially high price. The general understanding is that maintaining an artificial price is sufficient for a claim, but the nuance can be debated, especially concerning the timing of reliance and price impact.

- New Frontier: Section 1348 (Title 18 Fraud Statutes):

- There’s been a recent trend of prosecutors using the federal mail and wire fraud statutes (18 U.S.C. §§ 1341, 1343) and Section 1348 (specifically targeting securities fraud) in cases traditionally brought under federal securities laws (like Section 10(b)).

- The Potential “Split”: When prosecuting under these broader fraud statutes, prosecutors sometimes argue that they don’t need to prove reliance in the same way as under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act, or even argue for a different materiality standard (as discussed previously). This creates a tension regarding the applicability of the carefully developed securities law standards like fraud-on-the-market reliance. Defense counsel would strongly argue that even when using Title 18 statutes for securities fraud, the well-established elements and presumptions of Section 10(b) should still apply.

- In essence, while the core fraud-on-the-market theory remains valid, its application is constantly being refined and debated, particularly concerning the evidence of market efficiency and price impact needed to certify a class action. This makes it a very active area of litigation and a frequent subject of appellate review.

- Despite the Supreme Court’s efforts to create a uniform standard in Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd., several circuit splits have continued to exist regarding the interpretation and application of the PSLRA’s heightened pleading requirements. The Supreme Court recently granted certiorari in the case of NVIDIA Corp. v. E. Ohman J:or Fonder AB to address and resolve some of these key disagreements but suquently dismisseal the appeal as improvidently granted.

The main circuit splits concern the following issues:

1. Pleading scienter based on internal company documents

- This is one of the most prominent splits that the Supreme Court would have considered in the NVIDIA case.

- Split: Some circuits require plaintiffs to plead with particularity the actual contents of internal company documents to establish a “strong inference” of scienter. Other circuits allow a complaint to survive a motion to dismiss based on lless-specific allegations about the existence of internal reports, combined with confidential witness accounts or other facts suggesting what those reports might have revealed.

- Example circuit positions:

- Require particular contents: Second, Third, Fifth, Seventh, and Tenth Circuits.

- Do not require particular contents: First and Ninth Circuits.

2. The use of expert opinions to allege falsity

- Split: The debate centers on whether a plaintiff in securities litigation can rely on an expert’s post-hoc opinion to satisfy the PSLRA’s requirement for particularized factual allegations of falsity. Some circuits have found that expert opinions cannot substitute for specific facts in the complaint, while others, like the Ninth Circuit in the NVIDIA case, have found otherwise.

- Example circuit positions:

- Expert opinions cannot substitute for facts: Second and Fifth Circuits.

- Expert opinions can substitute for facts: Ninth Circuit (position being challenged in NVIDIA).

3. “Collective corporate scienter”

- This split concerns how to determine a corporation’s state of mind when it is alleged in securities class action lawsuits that different employees knew different pieces of information relevant to the alleged fraud.

- Split: Some circuits in securities class action lawsuits have adopted a “collective scienter” doctrine, allowing the knowledge and states of mind of various corporate employees and agents to be aggregated to establish a strong inference of corporate scienter. Other circuits reject or limit this aggregation theory, requiring plaintiffs to tie the scienter to specific, high-level individuals.

- Example approaches:

- Allowing aggregation: This is not a uniform approach, with courts considering various methods for aggregating knowledge

- Focusing on key decision-makers: The Sixth Circuit has adopted a middle-ground approach that allows for the aggregation of scienter among key decision-makers but not across the board.

- Tying scienter to specific speakers: Some circuits require a stronger link to the individual who made the misstatement.

Impact of the splits

- The existence of these circuit splits has created inconsistencies in the adjudication of securities fraud cases across the country. The standard for surviving a motion to dismiss can vary significantly depending on the federal circuit in which a case is filed, which can encourage forum shopping and create uncertainty for both investors and companies.

Destablizing Entire Markets

- Volatility and Uncertaintly: On a broader scale, securities fraud can destabilize entire markets. When fraudulent activities are uncovered, they often result in sharp declines in stock prices, not just for the companies involved but across the market. This can lead to increased volatility and uncertainty, affecting not only individual investors but also institutional investors such as pension funds and mutual fund who frequently server as lead plaintiffs in securities class action lawsuits.

- Entire Enconomy: The ripple effects can extend to the economy as a whole, impacting economic growth and stability. For example, the Enron scandal and the 2008 financial crisis are stark reminders of how securities fraud can have widespread and long-lasting economic impacts.

- Regulary Enforcement: Furthermore, securities fraud can lead to increased regulatory scrutiny and intervention, which can impose additional costs on companies and investors. While necessary to maintain market integrity, these regulatory measures can also slow down market activities and innovation.

- Long-Term Impact: The long-term impact on the market can be a loss of competitiveness and a shift in investor focus towards more heavily regulated, and potentially less innovative, market sectors. Understanding these impacts is crucial for all market participants to appreciate the importance of vigilance and compliance in securities trading.

Key Laws and Regulations Governing Securities Fraud

- Regulatory Compliance: The regulatory framework governing securities fraud is extensive and continually evolving to address new challenges in the financial markets. In the United States, the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 form the cornerstone of securities regulation.

- The Securities Act aims to ensure transparency in financial statements so that investors can make informed decisions, while the Securities Exchange Act established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to enforce federal securities laws.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act: A Watershed Moment

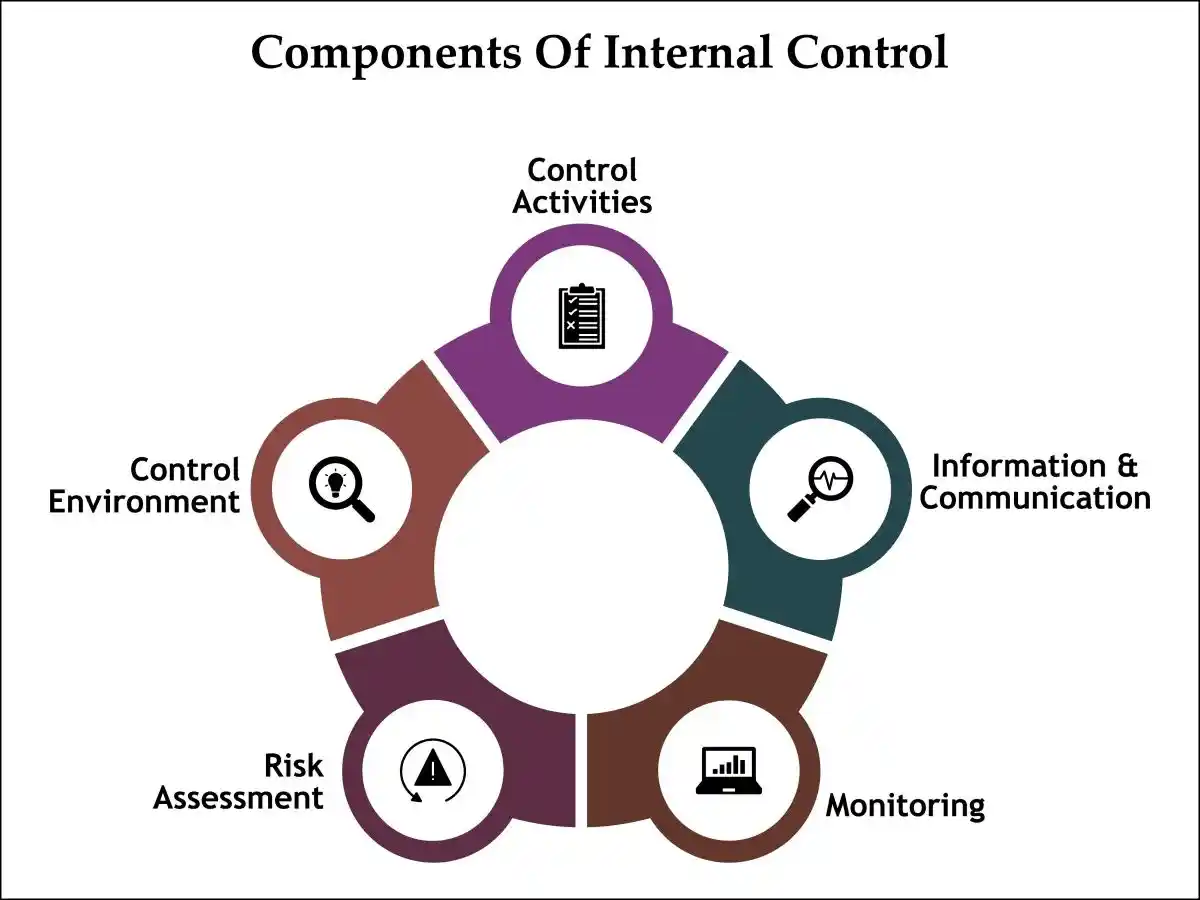

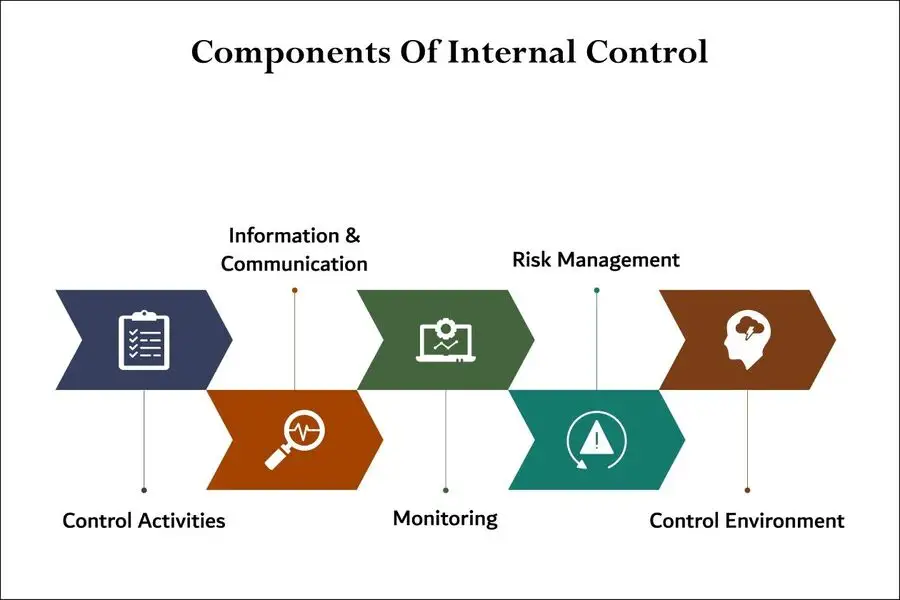

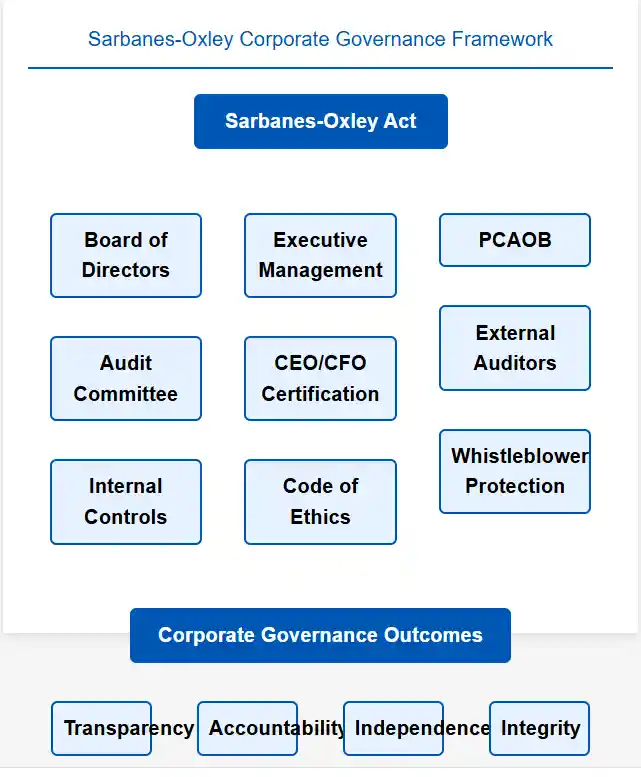

- The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002: Represents one of the most significant pieces of securities legislation in modern history. Enacted in response to major corporate scandals including Enron and WorldCom, this legislation fundamentally transformed corporate governance and internal controls requirements for public companies. The Act established the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB oversight) to regulate auditing firms and created stringent regulatory reporting requirements that companies must follow.

- Under Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, public companies must establish and maintain adequate internal controls over financial reporting. Management must assess the effectiveness of these controls annually, and external auditors must attest to management’s assessment. This requirement has significantly increased the cost of compliance but has also enhanced the reliability of financial reporting. Companies that fail to maintain adequate internal controls face severe penalties, including potential delisting from stock exchanges.

- The Sarbanes-Oxley Act also established ccriminal penalties for securities violations, with CEOs and CFOs facing up to 20 years in prison for knowingly certifying false financial statements. This personal accountability provision has fundamentally changed how corporate executives approach financial reporting and regulatory compliance.

SEC Enforcement and Regulatory Penalties

- SEC Enforcement Actions: Have become increasingly sophisticated and aggressive in recent years. The Commission has expanded its use of data analytics to identify potential violations and has increased coordination with criminal prosecutors. SEC penalties for securities fraud can include disgorgement of ill-gotten gains, civil monetary penalties, and officer and director bars that prevent individuals from serving in executive roles at public companies.

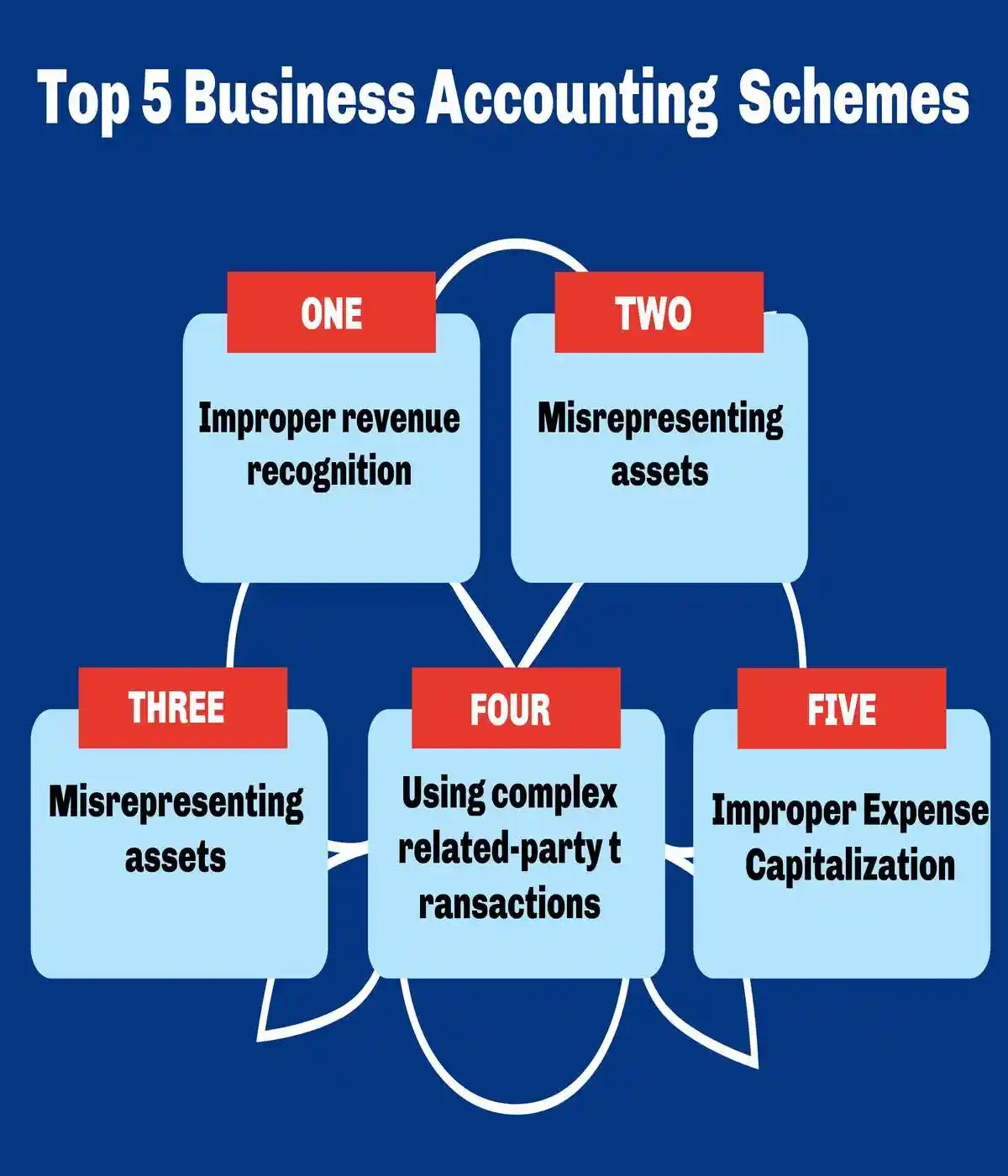

- Recent SEC Enforcement: Ttrends show a particular focus on accounting fraud cases involving revenue recognition, expense manipulation, and asset valuation issues. The Commission has also prioritized cases involving disclosure failures related to cybersecurity, climate risks, and other emerging areas of concern for investors.

Securities Class Actions and the Litigation Process

- Securities class actions: Serve as a critical enforcement mechanism that complements government regulation. These lawsuits allow investors who suffered losses due to securities fraud to band together and seek compensation from companies and their executives. The securities litigation process typically follows a predictable pattern that can span several years.

- Litigation Process: The process begins when a company’s stock price declines following disclosure of negative information. If investors believe the company previously made material misrepresentations, they may file a securities class action lawsuit alleging violations of federal securities laws. The court then determines whether to certify the case as a class action, allowing all similarly situated investors to participate in the lawsuit.

- Securities class action lawsuits often result in substantial settlements These settlements provide compensation to investors while also serving as a deterrent to future corporate misconduct.

Corporate Governance and Internal Controls

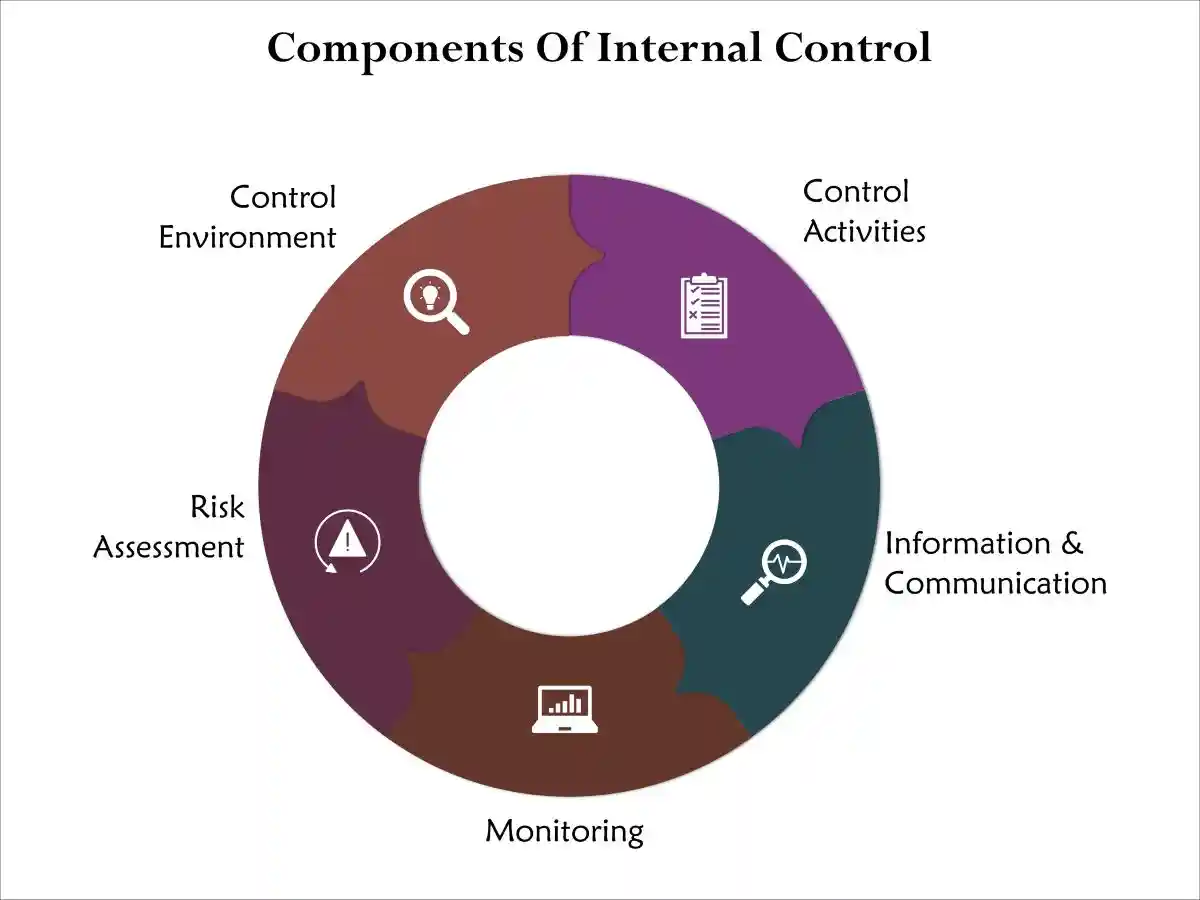

- Effective Corporate Governance: Serves as the first line of defense against securities fraud. Companies with strong governance structures, including independent boards of directors, robust audit committees, and comprehensive internal controls, are significantly less likely to experience fraud-related problems. The integration of ethical guidelines with operational controls creates multiple layers of protection against fraud and misconduct.

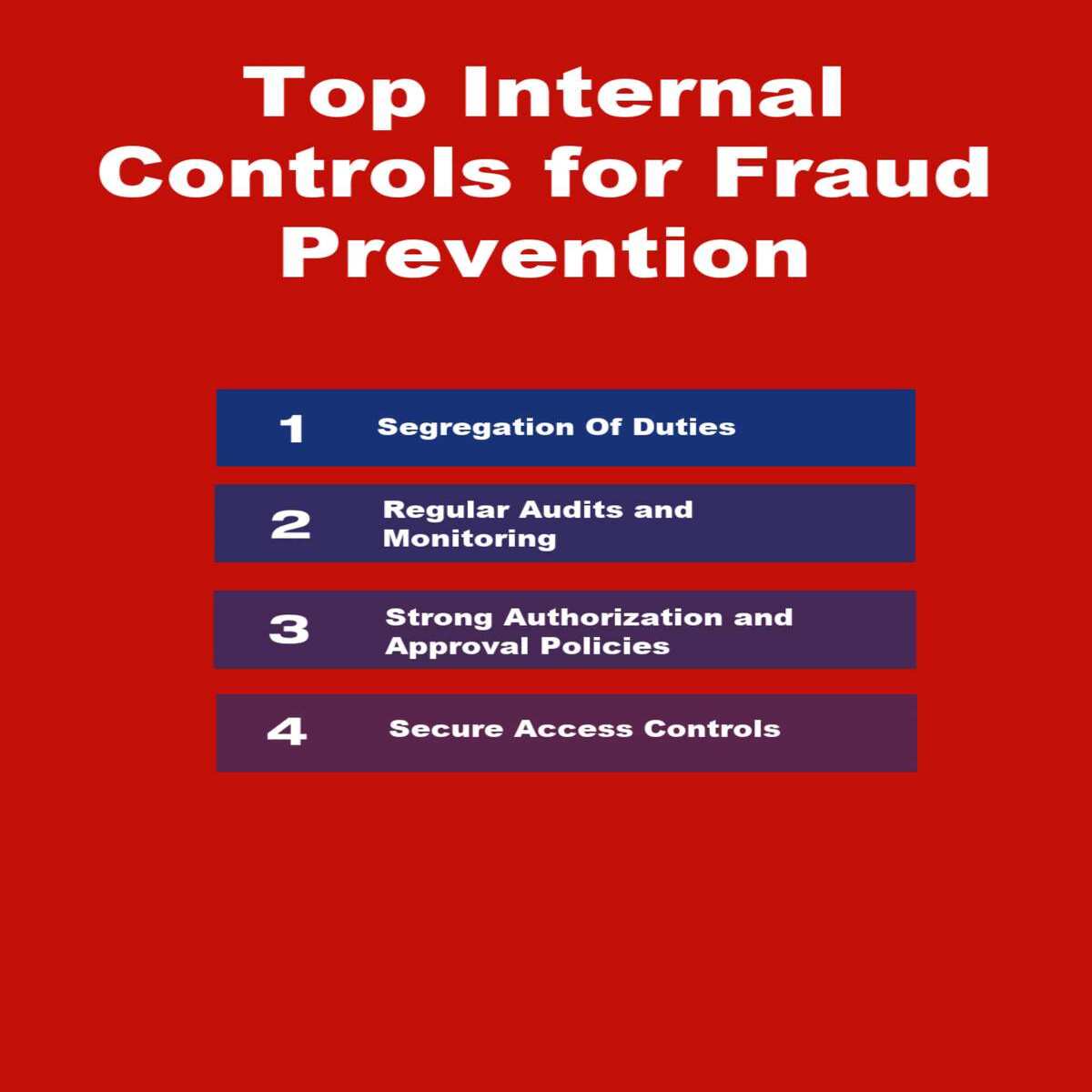

- Internal Controls: Encompass the policies and procedures companies implement to ensure accurate financial reporting and compliance with applicable laws and regulations. These controls must address authorization of transactions, segregation of duties, proper documentation, and regular monitoring of financial activities. Companies that invest in comprehensive internal controls systems not only reduce their fraud risk but also improve operational efficiency and regulatory compliance:

- The Importance of Corporate Governance: Extends beyond fraud prevention to encompass broader stakeholder interests. Companies with strong governance practices typically experience better long-term performance, lower cost of capital, and enhanced reputation in the marketplace. Investors increasingly consider governance factors when making investment decisions, recognizing that strong governance correlates with sustainable business success. The beneifits of stong internal controls and corporate governance are worth not pulling the trigger to securities litigation.

Prevention Strategies and Regulatory Compliance

- Regulatory compliance: Requires a proactive approach that goes beyond merely meeting minimum legal requirements. Companies must develop ccomprehensive compliance programs that address the specific risks in their industry and business model. These programs should include regular risk assessments, employee training, monitoring systems, and clear escalation procedures for potential violations. They must implement strong internal controls.

- Employee education plays a crucial role in fraud prevention: Companies must ensure that all personnel understand their responsibilities under securities laws and company policies. This education should cover not only what constitutes securities fraud but also the reporting mechanisms available for employees who observe potential violations. Whistleblower programs, protected under various federal laws, provide important channels for early detection of fraudulent activities. This is accoumplished by created a strong corporate governanced framework.

- The Importan Role of Technology: Technology increasingly plays a vital role in fraud prevention and detection. Advanced analytics, artificial intelligence, and blockchain technologies offer vital role in fraud prevention and detection.transactions, identifying unusual patterns, and maintaining accurate records. Companies that leverage these technologies effectively can significantly enhance their ability to prevent and detect securities fraud.

- The Cost Pays Off in Long Term Sucees: The cost of prevention invariably proves far less than the price of remediation. Companies that experience securities fraud face not only SEC penalties and securities class action settlements but also increased audit costs, higher insurance premiums, difficulty accessing capital markets, and long-term reputational damage. By implementing comprehensive prevention strategies, companies protect themselves from these devastating consequences while building sustainable competitive advantages.

Future Outlook and Emerging Challenges: Internal Controls and a Strong Corporate Governance Framework

- Evolving Landscape: The landscape of securities regulation continues to evolve in response to new technologies, changing business models, and emerging risks. Regulatory enforcement agencies are adapting their approaches to address cryptocurrency fraud, artificial intelligence-related disclosures, and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting issues. Companies must stay abreast of these developments to ensure ongoing regulatory compliance and strong internal controls and a robust corporate governance frameword.

- Glogal Litigation Landscape: Securities Fraud and Securities Litigation is increasing, creating more consistent global standards for internal controls and fraud prevention. This harmonization benefits multinational companies by reducing compliance complexity while enhancing investor protection across borders.

- The Future Lies in Robust Corporate Governance Frameworks: As we look toward the future, the intersection of technology and regulation will continue to shape the securities fraud landscape. Companies that embrace transparency, invest in robust internal controls, and maintain strong corporate governance practices will be best positioned to navigate these challenges successfully. The investment in effective controls represents not merely a compliance obligation but a fundamental business imperative that supports long-term success and market confidence. Companies looking for long-term sucees must implement robust corporate governance frameworks.

- Regulatory Enforcement: By understanding these complex dynamics and implementing comprehensive prevention strategies, investors and companies can work together to maintain the integrity of our financial markets while fostering innovation and economic growth. The ongoing evolution of securities litigation and regulatory enforcement ensures that those who violate securities laws face meaningful consequences, while those who operate with integrity benefit from enhanced market confidence and investor trust.

Contact Timothy L. Miles Today for a Free Case Evaluation

If you suffered substantial losses and wish to serve as lead plaintiff in a securities class action, or have questions about securities class action settlements, internal controls, corporate governance, regulatory compliance, or just general questions about your rights as a shareholder, please contact attorney Timothy L. Miles of the Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles, at no cost, by calling 855/846-6529 or via e-mail at [email protected]. (24/7/365).

Timothy L. Miles, Esq.

Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles

Tapestry at Brentwood Town Center

300 Centerview Dr. #247

Mailbox #1091

Brentwood,TN 37027

Phone: (855) Tim-MLaw (855-846-6529)

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.classactionlawyertn.com

Facebook Linkedin Pinterest youtube

Visit Our Extensive Investor Hub: Learning for Informed Investors