Introduction to Pleading Standards in Securities Litigation

The pleading standards in securities litigation sets a high bar for plaintiffs. Companies traded on U.S. exchanges face a 3.9% likelihood of securities litigation this year, slightly above the historic average. Pleading standards in securities litigation serve as the critical gateway determining which cases advance to discovery and which face dismissal at the earliest stage.

The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA), enacted nearly 30 years ago, established the framework under which just over 200 securities class actions are filed annually on average. Several significant developments emerged throughout 2024:

• Securities litigation filings remained consistent with historical patterns, showing a slight increase in core filings

• COVID-19 related securities class actions increased substantially, with seven filed during the first half of 2024

• Supreme Court docket included four securities cases in 2024, an unusually high number compared to prior years

• Materiality standards for securities fraud claims under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 are currently under Supreme Court review

The financial stakes in these cases reach astronomical levels. U.S. corporate exposure to alleged Rule 10b-5 violations hit $321.1 billion in 2019, with landmark settlements establishing extraordinary precedents—Enron at $7.2 billion, WorldCom at $6.2 billion, and Tyco International at $3.2 billion.

The Supreme Court’s consideration of multiple securities-related cases positions upcoming decisions to resolve existing circuit splits and provide essential clarity to securities class action adjudication. This detailed analysis examines the complex pleading requirements investors face in securities litigation, outlining step-by-step what plaintiffs must establish and what defendants can challenge through 2025 and beyond.

Understanding these pleading standards empowers investors to better assess the viability of potential claims and navigate the complexities of securities litigation with greater confidence. The heightened pleading standards established by the PSLRA create significant hurdles, yet meritorious cases with proper foundation continue to achieve substantial recoveries for defrauded investors.

- Rise of AI litigation: The number of lawsuits citing AI-related issues more than doubled in 2024, with 15 filings compared to seven in 2023. This was heavily concentrated in the technology sector and is linked to “AI washing”—when companies are alleged to have exaggerated their AI capabilities.

- Increased filings in specific sectors: The consumer non-cyclical sector, which includes pharmaceuticals and biotechnology companies, saw a significant increase in filings in 2024.

- Larger, more established company targets: Plaintiffs shifted their focus toward larger, more established companies instead of mainly targeting newly public firms, which had been a trend between 2020 and 2022.

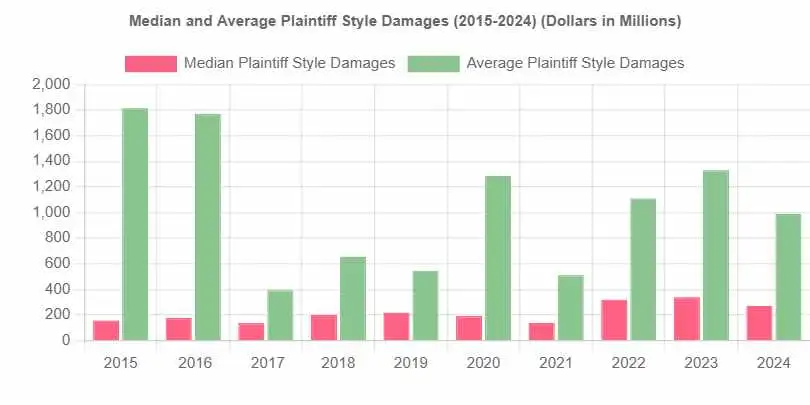

- Higher disclosed dollar loss: While the number of total filings remains in line with recent trends, the potential financial impact of individual lawsuits has grown. The average Disclosed Dollar Loss (DDL)—the estimated financial damage—in 2024 was nearly double the long-term historical norm.

- Decline in other litigation categories: Lawsuits related to special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), cryptocurrency, and cybersecurity continued to trend downward in 2024.

Understanding the Legal Framework

Securities litigation operates within a structured legal framework establishing stringent requirements for bringing and maintaining claims. To fully grasp the pleading standards in securities litigation, investors must first understand the foundational laws and regulations governing these actions.

What is Rule 10b-5 and Section 10(b)?

Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act serves as the cornerstone of securities fraud litigation, making it unlawful to “use or employ, in connection with the purchase or sale of any security” a “manipulative or deceptive device or contrivance”. This powerful provision operates as a “catchall” section imposing liability for material misstatements or omissions related to securities transactions.

Rule 10b-5, promulgated by the SEC under Section 10(b), specifically prohibits three distinct categories of conduct:

• Employing any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud

• Making untrue statements of material facts or omitting material facts

• Engaging in any act or practice that operates as a fraud upon any person

Essential elements for Rule 10b-5 claims: Plaintiffs seeking to prevail in a Rule 10b-5 action must establish six fundamental elements:

- A false or misleading statement/omission of material fact

- Connection to the purchase/sale of a security

- Loss causation

Rule 10b-5 applies to both public offerings and private placements, making it “the most heavily relied upon provision in private securities litigation”. This broad applicability provides investors with a powerful tool for addressing securities fraud across various market contexts.

The role of the Securities Act and Exchange Act

The two principal federal securities statutes—the Securities Act of 1933 and the Exchange Act of 1934—establish different liability frameworks that investors should understand when evaluating potential claims.

Securities Act of 1933 framework: The Securities Act primarily governs initial public offerings and other securities issuances, registration requirements for securities, and disclosure obligations in registration statements. This Act includes two key liability provisions particularly relevant for investors:

Section 11 imposes civil liability for material misstatements in registration statements, typically without requiring proof of reliance, causation, or scienter. This provision offers a more accessible path for investors who purchased securities in registered offerings.

Section 12 creates liability for selling unregistered securities or making material misstatements in prospectuses, generally without requiring scienter. This section provides additional protection for investors in both registered and unregistered offerings.

Exchange Act of 1934 framework: The Exchange Act focuses on ongoing reporting obligations, trading in secondary markets, market manipulation, and insider trading. This Act governs most day-to-day securities transactions that investors encounter.

Plaintiffs bringing claims under the Securities Act’s Sections 11 and 12 face a significantly lower burden than those proceeding under Section 10(b), as scienter is not typically required for these actions. This distinction creates strategic considerations for investors and their counsel when determining the most appropriate legal theory for pursuing claims.

How the PSLRA changed securities litigation

Prior to 1995, Congress identified significant abuses in securities litigation, with companies frequently facing “frivolous securities lawsuits in the hopes of extracting quick settlements”. Congress responded by enacting the PSLRA, which fundamentally altered the securities litigation landscape.

Major PSLRA reforms affecting investor rights:

Heightened pleading standards: Plaintiffs must state with particularity what misleading statements were made, why they were misleading, and facts giving rise to a “strong inference” of scienter. This requirement forces investors to conduct more thorough pre-filing investigations.

Lead plaintiff selection process: The Act created a system for appointing lead plaintiffs based on financial interest, discouraging “professional plaintiffs” motivated by bounty payments. This reform typically favors institutional investors with substantial losses.

Automatic discovery stay: The PSLRA prevents plaintiffs from conducting discovery while a motion to dismiss is pending, eliminating “fishing expeditions”. This provision protects defendants but requires plaintiffs to develop stronger cases before filing.

Safe harbor for forward-looking statements: Companies receive protection for projections identified as forward-looking when accompanied by meaningful cautionary language. Investors must carefully evaluate whether challenged statements fall within this protective provision.

Proportionate liability system: Less culpable parties (like auditors) gained relief from joint and several liability in certain circumstances. This change affects recovery strategies for investors seeking to maximize compensation.

Mandatory sanctions provision: The Act created a presumption that FRCP 11 violations warrant attorney’s fees and costs to the prevailing party. This provision discourages frivolous claims but also raises stakes for legitimate cases.

Congress subsequently addressed plaintiffs’ attempts to circumvent the PSLRA through state court filings by enacting the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act of 1998 (SLUSA), which directed most securities class actions into federal courts.

These reforms collectively raised the threshold for securities litigation, allowing courts to dismiss questionable claims before expensive discovery begins while preserving pathways for meritorious cases to proceed. For investors, understanding these requirements proves essential for assessing the viability of potential securities fraud claims and selecting appropriate legal strategies.

PRE- AND POST-PSLRA STANDARDS FOR SECURITIES FRAUD LITIGATION

Feature | Pre-PSLRA Standard | Post-PSLRA Standard |

| Motion to dismiss | Based on “notice pleading” (Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(a)), making it easier for plaintiffs to survive motions to dismiss. This often led to settlements to avoid costly litigation. | Requires satisfying PSLRA’s heightened pleading standards and the “plausibility” standard from Twombly and Iqbal. Failure to plead with particularity on any element can result in dismissal. |

| Pleading | “Notice pleading” was generally sufficient, though fraud claims under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b) required particularity for the circumstances of fraud, but intent could be alleged generally. | Each misleading statement must be stated with particularity, explaining why it was misleading. Facts supporting beliefs in claims based on “information and belief” must also be stated with particularity. |

| Scienter | Pleaded broadly; the “motive and opportunity” test was often sufficient to infer intent. | Requires alleging facts creating a “strong inference” of fraudulent intent, which must be at least as compelling as any opposing inference of non-fraudulent intent, as clarified in Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd.. |

| Loss causation | Not a significant pleading hurdle, often assumed if a plaintiff bought at an inflated price. | Requires pleading facts showing the fraud caused the economic loss, often by linking a corrective disclosure to a stock price drop. Dura Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Broudo affirmed this. |

| Discovery | Could proceed while a motion to dismiss was pending. | Automatically stayed during a motion to dismiss. |

| Safe harbor for forward-looking statements | No statutory protection. | Protects certain forward-looking statements if accompanied by “meaningful cautionary statements”. |

| Lead plaintiff selection | Often the first investor to file. | Court selects based on a “rebuttable presumption” that the investor with the largest financial interest is the most adequate. |

| Liability standard | For non-knowing violations, liability was joint and several. | For non-knowing violations, liability is proportionate; joint and several liability applies only if a jury finds knowing violation. |

| Mandatory sanctions | Available under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11, but judges were often reluctant to impose them. | Requires judges to review for abusive conduct |

The Heightened Pleading Standard Explained

The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) fundamentally reshaped securities litigation through heightened pleading standards that serve as the primary filter determining which cases advance beyond initial challenges. These rigorous requirements create an early checkpoint where courts evaluate the sufficiency of investor allegations before costly discovery begins.

Why the PSLRA raised the bar

Congress enacted the PSLRA in 1995 to address what it characterized as “abusive practices committed in private securities litigation”. The legislative record demonstrates specific concerns about litigation practices that Congress viewed as harmful to market integrity:

• Strike suit epidemic: The “routine filing of lawsuits against issuers of securities” occurred whenever stock prices dropped significantly, regardless of whether actual fraud had occurred

• Economic damage: Congress identified “baseless and extortionate securities lawsuits” as threats that injured “the entire U.S. economy”

• Discovery abuse: Plaintiffs used the discovery process as leverage to force settlements in cases lacking merit

The PSLRA targeted lawsuits filed with “only faint hope that the discovery process might lead eventually to some plausible cause of action”. The Act’s heightened pleading standards were designed to eliminate speculative claims early, preventing plaintiffs from using the threat of expensive discovery to extract settlements from defendants.

What plaintiffs must now prove in securities litigation

The PSLRA establishes demanding pleading requirements across three essential elements:

1. Specificity for misleading statements

Plaintiffs face strict requirements when alleging false or misleading statements: • Must “specify each statement alleged to have been misleading” • Must identify “the reason or reasons why the statement is misleading” • For allegations based on “information and belief,” must “state with particularity all facts on which that belief is formed”

2. Scienter (fraudulent intent)

The mental state requirement creates perhaps the highest hurdle: • Plaintiffs must “state with particularity facts giving rise to a strong inference that the defendant acted with the required state of mind” • The Supreme Court established in Tellabs that this “strong inference” must be “cogent and at least as compelling as any opposing inference of nonfraudulent intent” • Courts evaluate the complaint holistically rather than examining individual allegations in isolation

3. Loss causation

Plaintiffs bear the burden of connecting fraud to financial harm: • Must prove “that the act or omission of the defendant caused the loss” • Post-Dura requirements mandate allegations that “share price fell significantly after the truth became known”

Circuit courts have developed conflicting interpretations regarding the specificity required for pleading both falsity and scienter. Some circuits demand that plaintiffs plead the actual contents of internal company documents when establishing scienter, while others permit more speculative allegations.

Impact on early-stage dismissals

The heightened pleading standard produces several significant effects on securities litigation:

Automatic discovery stay: The PSLRA imposes a complete discovery stay until courts resolve motions to dismiss, preventing plaintiffs from using discovery to develop their cases.

Motion practice increase: Statistical analysis reveals more than a 50% increase in motion to dismiss filings following the PSLRA’s implementation.

Access to justice concerns: Evidence suggests that individual plaintiffs fare worse than institutional litigants under heightened pleading standards, raising questions about equal access to legal remedies.

Enhanced pre-filing investigation: The dismissal threat under heightened pleading standards compels plaintiffs to conduct more extensive factual investigation before filing complaints.

Circuit inconsistencies: Varying interpretations of PSLRA requirements across different courts create inconsistent pleading standards, particularly regarding the specificity required for scienter allegations based on internal company documents.

Motions to dismiss frequently target the adequacy of scienter and falsity allegations, establishing the pleading stage as the critical battleground in securities litigation. The Supreme Court’s pending decisions on pleading requirements will carry “exceptionally significant consequences for businesses facing the threat of securities litigation”.

Understanding these heightened standards proves essential for investors evaluating potential securities fraud claims. The PSLRA’s requirements create substantial obstacles, yet properly supported cases continue to achieve meaningful recoveries for investors harmed by corporate misconduct.

Scienter: Proving Intent or Recklessness

Proving scienter represents the most challenging hurdle investors face in securities fraud litigation. This fundamental element of liability separates fraudulent misconduct from mere negligence, often determining whether a case survives the crucial motion to dismiss stage.

Definition and legal threshold

Scienter refers to a “mental state embracing intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud“. Courts recognize two primary paths for establishing this culpable state of mind:

Actual intent – Demonstrating the defendant knowingly made false statements Recklessness – Showing behavior that represents “an extreme departure from the standards of ordinary care”

The definition of recklessness varies significantly across jurisdictions, creating strategic considerations for where investors file claims:

First Circuit: Defines recklessness as a “highly unreasonable omission” presenting a danger of misleading investors “that is either known to the defendant or is so obvious the actor must have been aware of it”

Second Circuit: Permits an inference of recklessness where defendants “failed to review information they had a duty to monitor” or “ignored obvious signs of fraud”

Ninth Circuit: Imposes a more stringent “deliberate recklessness” standard, requiring evidence closer to actual intent

Under the PSLRA, plaintiffs must “state with particularity facts giving rise to a strong inference that the defendant acted with the required state of mind”. The Supreme Court clarified in Tellabs that this “strong inference” must be “cogent and at least as compelling as any opposing inference of nonfraudulent intent”.

Internal documents as evidence of scienter

Corporate internal documents often provide the strongest evidence for establishing scienter, though pleading requirements for such documents remain highly contentious:

- Contradictory internal reports: Plaintiffs frequently allege that defendants had access to internal reports contradicting their public statements

- Extrinsic materials: Courts may consider relevant extrinsic materials when determining whether allegations collectively suggest scienter

- Defensive use: Defendants can defeat scienter allegations by introducing extrinsic documents that directly contradict allegations in the complaint

- Corporate defendants present unique challenges because they lack “discrete minds” and “think only through their employees, officers, and agents”. This creates difficult questions about whose knowledge should be attributed to the corporation:

- Some courts consider knowledge of various corporate employees in aggregate

- Others reject this “collective scienter” approach

- Alternative frameworks include respondeat superior, collective scienter, and the high managerial agent approach

Circuit splits create strategic opportunities

A significant circuit split has emerged regarding how specifically plaintiffs must plead internal documents to establish scienter:

Restrictive circuits (Second, Third, Fifth, Seventh, and Tenth): Require plaintiffs to plead “with particularity the actual contents” of internal documents

Permissive circuits (First and Ninth): Allow more speculative allegations about what internal records “might have said”

The NVIDIA case: A crucial test

The NVIDIA case exemplifies this critical split and its implications for investors:

• Allegations: Plaintiffs alleged NVIDIA misrepresented the extent to which GPU revenues came from gamers versus cryptocurrency miners

• Internal data claims: They claimed executives had access to internal data sources showing high crypto-related demand

• District court ruling: The court dismissed the complaint, finding plaintiffs failed to “adequately tie the specific contents of any data sources to particular statements”

• Ninth Circuit reversal: The appellate court accepted allegations about a “detailed sales database” and the CEO’s “detail-oriented management style”

• Supreme Court review: The Court granted certiorari to address whether plaintiffs must “plead with particularity the contents of internal company documents” to establish scienter but then appeal was “dismissed as improvidently granted.”

Falsity and the Role of Expert Opinions

Falsity allegations establish the foundational cornerstone in securities litigation. Under the PSLRA, plaintiffs cannot simply assert that statements were false—they must demonstrate precisely why those statements were false with particularity and legal precision.

What constitutes a false statement

False statements in securities litigation must satisfy specific criteria to support viable claims:

- Material misrepresentation: The statement must misrepresent or omit facts that a reasonable investor would consider important to their investment decision

- Specificity requirement: Plaintiffs must “specify each statement alleged to have been misleading” and explain precisely why each identified statement was false or misleading

- Particularized allegations: For allegations made on “information and belief,” plaintiffs must “state with particularity all facts on which that belief is formed“

Courts evaluate falsity by examining whether the statement in question would mislead a reasonable investor considering the “total mix of information available.” Even technically accurate statements can become actionable if they create a materially false impression for investors.

Can expert reports substitute for factual allegations?

A significant circuit split has emerged regarding whether expert opinions can substitute for factual allegations at the pleading stage:

Restrictive approach (2nd and 5th Circuits):

- Expert opinions cannot substitute for particularized factual allegations

- Plaintiffs must plead actual facts demonstrating falsity

- Expert analysis alone is insufficient to satisfy the PSLRA’s heightened pleading requirements

Permissive approach (9th Circuit):

- Expert opinions may be considered if deemed reliable and supported by other allegations

- Expert analysis can help establish falsity when based on publicly available data

- Expert reports may strengthen a complaint when accompanied by witness statements and corroborating market events

The debate centers on fundamental questions about what constitutes “particularity” under the PSLRA. Critics of the permissive approach argue it undermines the act’s purpose of filtering out speculative claims before costly discovery begins. Proponents contend that expert analysis represents the most practical method for plaintiffs to plead falsity without access to internal company information.

The NVIDIA case and its implications for investors

The NVIDIA case exemplifies this crucial pleading standard debate:

- Case background: Plaintiffs alleged NVIDIA misrepresented the extent to which GeForce GPU revenue came from cryptocurrency miners versus gamers

- Evidentiary challenge: Plaintiffs lacked access to NVIDIA’s internal revenue breakdown data

- Expert solution: Plaintiffs relied on an expert consulting firm (Prysm) to analyze NVIDIA’s crypto-related revenue using publicly available data

- Ninth Circuit ruling: The court found falsity adequately alleged based on:

- The expert (Prysm) report’s analysis

- A separate third-party (RBC) report with similar conclusions

- Former employee statements confirming crypto miners purchased “enormous numbers” of GPUs

- Post-class period admission by the CEO about a “crypto hangover” affecting revenues

The Supreme Court granted certiorari to address whether “plaintiffs can satisfy the PSLRA’s falsity requirement by relying on an expert opinion to substitute for particularized allegations of fact”, but subsequently dismissed the case as “improvidently granted”.

Despite this dismissal, the case’s implications remain significant for investors and their counsel. Courts must balance the PSLRA’s gatekeeping function against practical realities facing plaintiffs without pre-discovery access to internal company data. Courts permitting expert opinions at the pleading stage will likely scrutinize their reliability through analysis resembling “quasi-Daubert” review, focusing on whether reports contain “questionable assumptions and unexplained reasoning”.

Defendants facing expert-supported complaints should challenge the reliability and specificity of these reports vigorously, while plaintiffs will likely employ expert analysis more frequently following the NVIDIA precedent. For investors evaluating potential securities claims, understanding whether their jurisdiction follows the restrictive or permissive approach becomes crucial for assessing case viability and litigation strategy.

Loss Causation and Corrective Disclosures

Loss causation represents the final hurdle plaintiffs must clear in securities class action lawsuits. This critical element establishes the direct connection between the defendant’s misrepresentation and the economic harm investors suffered.

Understanding loss causation requirements

Loss causation serves as the proximate cause element in securities fraud litigation, focusing specifically on the link between misrepresentation and subsequent corrective disclosure. Plaintiffs must establish three essential components:

- Causal connection between the alleged fraud and the economic loss

- Timing requirement – the plaintiff sold shares after (not before) the corrective disclosure occurred

- Proximate cause – the defendant’s misrepresentation, rather than other market factors, directly caused the loss

Loss causation differs fundamentally from reliance or transaction causation in crucial ways:

- Transaction causation (reliance) concerns the misrepresentation itself

- Loss causation focuses on the relationship between the misrepresentation and corrective disclosure

The Supreme Court’s decision in Dura Pharmaceuticals v. Broudo established that merely alleging an artificially inflated purchase price is insufficient—plaintiffs must prove the misrepresentation actually caused economic loss.

How courts analyze corrective disclosures in securities litigation

- Corrective disclosure occurs when “information correcting the misstatement or omission that is the basis for the action is disseminated to the market”. Courts apply different standards when evaluating these disclosures:

- Some circuits require only that the disclosure reveals part of the truth about the misrepresentation

- Others demand a more direct link between the disclosure and the original false statement

- Pleading standards for loss causation also vary by circuit:

- Some apply the lenient Rule 8(a) standard

- Others require the more stringent Rule 9(b) fraud-specific standard

- Courts examine several key factors when evaluating corrective disclosures:

- Whether the disclosure explicitly identifies the alleged misrepresentation as false

- Potential alternative explanations for price decline

- Specificity match between the misrepresentation and correction

The “mismatch” issue became central in Goldman Sachs v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, where the Supreme Court held that a “mismatch in specificity between a misstatement and corrective disclosure makes it less likely that the specific disclosure actually corrected the generic misrepresentation”.

Short-seller reports face increased scrutiny in securities litigation

Approximately 14% of alleged corrective disclosures in 2021 relied on stock price declines linked to short-seller reports. Courts increasingly restrict their use due to several concerns:

Primary limitations include:

- Credibility concerns – Courts question reports from authors with financial incentives to drive down stock prices

- Anonymous sourcing – Reports quoting anonymous sources face heightened judicial scrutiny

- Accuracy disclaimers – Reports that disclaim their own accuracy are frequently rejected

- Recycled information – Reports merely repeating publicly available information typically fail to qualify as corrective disclosures

Recent circuit court developments:

- Fourth Circuit (following the Ninth) ruled that anonymously sourced reports disclaiming accuracy cannot support loss causation

- Eleventh Circuit held that analyst reports merely repeating public information cannot serve as corrective disclosures

- Ninth Circuit established a two-step framework in In re BofI Holding, requiring plaintiffs to explain why public information in a report wasn’t already reflected in the stock price

Requirements for viable short-seller corrective disclosures

For a short-seller report to potentially qualify as a corrective disclosure, courts require:

- New information – Provide previously undisclosed information

- Specific substantiation – Cite specific, verifiable facts supporting claims

- Source reliability – Avoid heavy reliance on anonymous sources or accuracy disclaimers

- Direct causation – Demonstrate a clear connection between the report and subsequent stock price decline

Understanding these requirements empowers investors to better assess the strength of potential loss causation arguments and the viability of their securities fraud claims. The strict standards established by courts reflect the fundamental principle that corrective disclosures must reveal genuine, previously concealed truths rather than speculation or repackaged public information.

Tracing and Standing in Section 11 Securities Litigation Claims

Tracing requirements present substantial obstacles for investors pursuing Section 11 claims in securities litigation. This essential standing element establishes which investors can bring claims under this powerful Securities Act provision.

The Slack decision and its implications for investors

The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Slack Technologies, LLC v. Pirani on June 1, 2023, established rigid requirements that plaintiffs must satisfy:

- Direct traceability: Investors must plead and prove they purchased shares traceable to the allegedly defective registration statement

- Application to direct listings: This requirement applies even in direct listings where registered and unregistered shares trade simultaneously

- Specific document connection: Investors must establish a direct link between their purchased shares and the particular document containing alleged misstatements

The Court rejected the Ninth Circuit’s more investor-friendly approach, determining that:

- Statutory interpretation: The statute imposes liability for false statements in “the registration statement” rather than any registration statement

- Narrow focus: The term “such security” limits the law’s scope to securities registered under the particular registration statement alleged to contain falsehoods

- Damages limitation: The damages cap in Section 11(e) restricts maximum recovery to the value of registered shares alone

This ruling provides a “formidable standing defense” to companies utilizing direct listings.

Challenges investors face in direct listings

Direct listings create particularly difficult tracing obstacles for investors:

- Traditional IPO advantage: Conventional IPOs include lockup periods where only registered shares initially trade, making tracing feasible during early trading

- Simultaneous trading: Direct listings offer registered and unregistered shares simultaneously, rendering tracing “impossible” from the initial trading day

- Slack example: The company’s 118 million registered shares and 165 million unregistered shares became available for trading at the same time

- Electronic format challenges: Without individualized paper certificates, all shares appear identical in electronic book-entry form

Third-party custodian arrangements, where shares are held in custodian names rather than beneficial owner names, create additional tracing complications.

Strategies for meeting tracing requirements

Given these substantial challenges, investors seeking to satisfy tracing requirements might consider:

- Focus on traditional IPOs: Target claims during lockup periods where only registered shares trade

- Direct offering purchases: Attempt to prove direct purchase participation in the offering itself

- Chain-of-title documentation: Establish complete chain-of-title evidence for aftermarket share purchases

The Slack decision renders Section 11 claims extremely challenging in direct listings. Judge Gallagher observed that “Section 11 defendants can structure their offerings to thwart tracing”. Courts increasingly recognize this “loophole” requires resolution through “statutory or regulatory changes” rather than judicial interpretation.

The strict tracing requirement effectively shields many direct listings from Section 11 liability, creating important strategic considerations for companies contemplating public offerings. This development significantly limits investor recourse in securities litigation under one of the most powerful securities law provisions, highlighting the importance of understanding these procedural barriers when evaluating potential securities claims in securities class actions.

Class Certification and Price Impact in Securities Litigation

Class certification serves as a pivotal battleground in securities litigation, where the success of class-wide claims frequently depends on demonstrating price impact through rigorous economic analysis.

The fraud-on-the-market theory

Fraud-on-the-market theory provides the foundation for class certification in securities class actions. This established economic principle operates on several key assumptions:

- Efficient markets rapidly incorporate all publicly available information, including misleading corporate statements

- Investors purchasing at market price rely on the integrity of that price as an accurate reflection of company value

- Material misrepresentations artificially inflate or deflate stock prices, affecting all purchasers regardless of whether they directly read the fraudulent statements

Plaintiffs seeking to invoke this presumption must establish three essential elements:

- The alleged misstatement was both public and material to investors

- The plaintiff purchased shares between the misstatement and subsequent truth revelation

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Basic v. Levinson (1988) created this presumption, effectively substituting “reliance on market price” for direct reliance on misstatements. This legal framework enables class-wide treatment of the reliance element, making securities class actions viable for large groups of investors.

Event studies and statistical analysis

Event studies represent the primary statistical methodology for proving or disproving price impact in securities litigation:

- These regression analyses measure whether specific disclosures caused statistically significant stock price movements

- Courts increasingly regard event studies as the preferred or required method for establishing price impact

- Most jurisdictions apply a 95% confidence level threshold when evaluating statistical significance

Event studies face several important constraints that investors should understand:

- Statistical limitations: Low power to detect economically meaningful price impacts, particularly for smaller effects

- Confirmatory statement problem: Inability to measure effects of statements that merely maintain existing price inflation

- Bundled disclosure issues: Limited capacity to separate impacts of multiple simultaneous announcements

Key Supreme Court decisions in Securities Litigation

Two critical Supreme Court rulings have clarified standards for challenging the fraud-on-the-market presumption:

Halliburton II (2014):

- Confirmed defendants’ right to rebut the presumption at class certification stage

- Permitted defendants to present direct evidence showing alleged misrepresentations lacked price impact

- Established that any evidence severing the connection between misrepresentations and price can defeat the presumption

Goldman Sachs (2021):

- Required courts to consider all relevant evidence regarding price impact, including the generic nature of alleged misstatements

- Emphasized that generic corporate statements are less likely to impact stock prices compared to specific factual assertions

- Assigned the burden of persuasion to defendants seeking to rebut the presumption

- Clarified that defendants must prove lack of price impact by a preponderance of evidence

The Court specifically addressed the “mismatch” problem, noting that discrepancies between generic misrepresentations and specific corrective disclosures reduce the likelihood that earlier statements actually impacted stock prices.

Practical implications for investors: These decisions create both opportunities and challenges. While defendants can now more effectively challenge class certification, investors in cases with strong price impact evidence and specific misstatements remain well-positioned to achieve class certification and proceed to recovery.

Strategic Considerations for Plaintiffs and Defendants in Securities Litigation

Strategic decisions made by both sides often determine the outcome of successful securities litigation. The demanding pleading standards established by the PSLRA require careful tactical planning throughout the litigation process.

Forum shopping and circuit splits

Venue selection creates significant strategic advantages and disadvantages:

- Circuit split exploitation: A clear circuit split exists between the Ninth and Seventh Circuits regarding forum selection clauses in corporate bylaws

- Delaware advantage: The Ninth Circuit enforces provisions requiring derivative claims to be filed in Delaware state court

- Corporate response: Delaware-incorporated companies increasingly adopt bylaws directing claims to Delaware courts

- Limiting plaintiff options: This trend potentially curtails plaintiff forum shopping and parallel litigation in multiple jurisdictions

The choice of jurisdiction can determine whether a case survives a motion to dismiss, making venue selection one of the most critical early strategic decisions in securities litigation.

Timing and discovery stays

Procedural timing frequently determines litigation success or failure:

- Automatic stay application: The PSLRA’s automatic discovery stay applies to “any private action” in both federal and state courts

- State court recognition: New York’s First Department became the first state appellate court to affirm this principle

- Discovery prevention: The stay prevents discovery until after a motion to dismiss is resolved

- Appeal exception: Yet, the stay doesn’t apply during appeals from denial of dismissal motions

This automatic discovery stay fundamentally shifts the tactical landscape, requiring plaintiffs to develop their strongest possible case before filing rather than relying on discovery to uncover supporting evidence.

Institutional investors and lead plaintiff selection

Lead plaintiff selection significantly influences both case outcomes and settlement values:

- Recovery advantages: Public pension funds correlate with higher recoveries as a percentage of potential damages

- Cost efficiency: These institutional investors recover larger settlements alongside lower attorney fees

- Target selection: Public pension funds particularly target controlling shareholder transactions

- Settlement leverage: Their political clout and media savvy may compel defendants to increase offer prices

The presence of a sophisticated institutional lead plaintiff often signals to defendants that the case will be vigorously prosecuted and well-funded, affecting settlement negotiations from the earliest stages.

Conclusion

Securities litigation pleading standards continue to evolve as courts apply the stringent PSLRA requirements established nearly three decades ago. Several critical developments shape the landscape for investors and their counsel moving forward:

• Pleading standards in securities litigation function as the decisive gateway determining case viability, with scienter allegations presenting the most significant challenge for plaintiffs seeking to survive motions to dismiss in a securities class action

• Circuit splits on core issues—expert opinion usage, internal document specificity requirements, and loss causation standards—create strategic advantages for informed litigants who understand jurisdictional differences

• Recent Supreme Court decisions in Slack and Goldman Sachs have reshaped litigation strategies, making Section 11 claims nearly impossible in direct listings while establishing clearer standards for challenging fraud-on-the-market presumptions

• Forum selection carries increased importance as Delaware-incorporated companies adopt bylaws directing securities claims to Delaware courts, limiting traditional plaintiff forum shopping strategies

• Institutional investors, particularly public pension funds, demonstrate superior outcomes with higher recovery rates and reduced attorney fees compared to individual plaintiff cases

• Timing considerations around the PSLRA’s automatic discovery stay create fundamental strategic decisions that often determine litigation success or failure

Forthcoming Supreme Court decisions will likely resolve existing circuit conflicts and provide greater certainty for securities fraud class actions. The enormous financial stakes—with billion-dollar settlements continuing to establish precedents—ensure securities litigation remains a critical area for investor protection efforts.

Companies must carefully evaluate their disclosure practices and internal controls to minimize litigation exposure, while plaintiffs’ counsel must conduct thorough pre-filing investigations to meet heightened pleading thresholds. These standards serve their intended function: eliminating speculative claims while preserving pathways for legitimate investor recovery.

The pleading requirements established by the PSLRA successfully balance deterring securities fraud against preventing abusive litigation practices. For investors who have suffered losses due to corporate misrepresentation or fraud, understanding these standards provides essential insight into the viability of potential claims and the importance of experienced legal representation.

Key Takeaways

Securities litigation pleading standards serve as critical gatekeepers that determine case viability before expensive discovery begins. Understanding these requirements is essential for both plaintiffs and defendants navigating this complex legal landscape.

• PSLRA heightened standards filter cases early: Plaintiffs must prove scienter with “strong inference,” specify why statements are misleading, and demonstrate loss causation—preventing frivolous lawsuits while allowing meritorious claims to proceed.

• Circuit splits create strategic forum shopping opportunities: Different courts interpret expert opinion use, internal document specificity, and scienter requirements differently, making venue selection crucial for litigation outcomes.

• Tracing requirements severely limit Section 11 claims: The Supreme Court’s Slack decision requires plaintiffs to prove shares were purchased from specific registration statements, making direct listing claims nearly impossible in securities class action lawsuits.

• Price impact evidence determines class certification: Event studies and fraud-on-the-market theory remain essential, but generic statements face heightened scrutiny under Goldman Sachs standards in securities class action lawsuits.

• Institutional investors drive better outcomes: Public pension funds as lead plaintiffs correlate with higher recoveries and lower attorney fees, while discovery stays prevent fishing expeditions during motion practice.

The stakes remain astronomical, with corporate exposure reaching hundreds of billions annually. As the Supreme Court continues resolving circuit splits, these pleading standards will likely become more uniform, requiring careful strategic planning from all parties involved in securities litigation.

FAQs

Q1. What is the heightened pleading standard in securities litigation? The heightened pleading standard requires plaintiffs in securities class actions to specify each misleading statement, explain why it was misleading, and provide facts giving a strong inference of scienter (fraudulent intent). This standard, introduced by the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act, aims to filter out frivolous lawsuits early in the process.

Q2. How do courts evaluate loss causation in securities fraud cases? Courts in securities class actions assess whether there’s a causal connection between the alleged fraud and economic loss. They examine if the stock price dropped following a corrective disclosure, whether other market factors might explain the decline, and the specificity match between the misrepresentation and correction. The burden is on plaintiffs to demonstrate this link.

Q3. What role do expert opinions play in securities litigation pleadings? The use of expert opinions in pleadings is contentious. Some courts allow expert analysis to help establish falsity, especially when based on public data. Others require more specific factual allegations. The debate centers on whether expert opinions can substitute for particularized facts under the heightened pleading requirements.

Q4. How has the Slack decision impacted Section 11 claims? The Supreme Court’s Slack decision requires plaintiffs to prove they purchased shares directly traceable to the allegedly defective registration statement. This makes Section 11 claims extremely difficult in direct listings where registered and unregistered shares trade simultaneously, effectively insulating many such offerings from this type of liability.

Q5. What is the significance of the fraud-on-the-market theory in securities class actions? The fraud-on-the-market theory is crucial for class certification in securities litigation. It allows plaintiffs to establish a presumption of reliance on misrepresentations by showing the stock traded in an efficient market. This theory enables class-wide treatment of the reliance element, making it easier to certify large investor classes.

Contact Timothy L. Miles Today for a Free Case Evaluation about Security Class Action Lawsuits

If you suffered substantial losses and wish to serve as lead plaintiff in a securities class action, or have questions about the securities litigation, or just general questions about your rights as a shareholder, please contact attorney Timothy L. Miles of the Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles, at no cost, by calling 855/846-6529 or via e-mail at [email protected].(24/7/365).

Timothy L. Miles, Esq.

Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles

Tapestry at Brentwood Town Center

300 Centerview Dr. #247

Mailbox #1091

Brentwood,TN 37027

Phone: (855) Tim-MLaw (855-846-6529)

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.classactionlawyertn.com

Visit Our Extensive Investor Hub: Learning for Informed Investors