Introduction to Securities Fraud Litigation

- Securities Fraud Litigation: Represents one of the most contentious battlegrounds in modern federal court practice, where the concept of scienter—fraudulent intent—determines which cases survive preliminary challenges and proceed to costly discovery.

- Corporate Setbacks: Plaintiffs routinely transform routine business disappointments into securities fraud class actions, alleging that companies possessed fraudulent intent when making earlier public statements about subsequently disclosed adverse events. This systematic approach to securities litigation creates substantial exposure for corporate defendants and demands sophisticated legal strategies for both prosecution and defense.

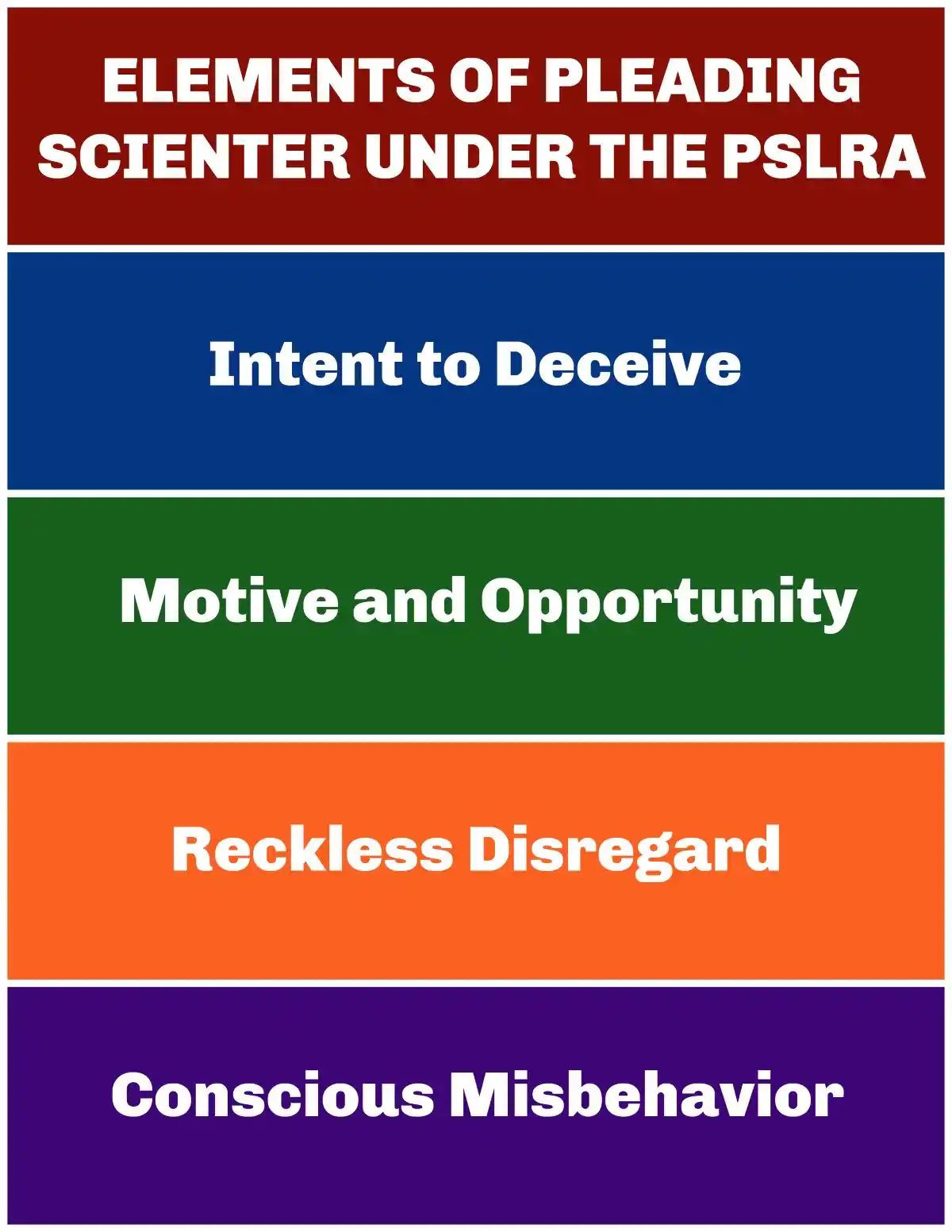

- PSLRA Requirements: The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 established formidable barriers for securities fraud litigation by requiring plaintiffs to plead a strong inference of scienter that satisfies heightened federal standards. These statutory requirements mandate that complaints “state with particularity facts giving rise to a strong inference that the defendant acted with the required state of mind”. The resulting pleading burden eliminates weak cases while creating tactical advantages for defendants seeking early dismissal.

- Section 10(b) Elements: Securities fraud: Claims under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 require six critical elements: material misrepresentation or omission, scienter, connection with securities transactions, reliance, damages, and loss causation. The scienter element focuses specifically on defendants’ intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud, though circuits disagree regarding the degree of recklessness sufficient to satisfy this mental state requirement.

- Essential Legal Knowledge: This guide examines the critical aspects of scienter pleading that practitioners must understand:

- Scienter definitions and legal requirements in securities fraud litigation

- Heightened pleading standards under PSLRA statutory framework

- Motive and opportunity, and also conscious misbehavior evaluation strategies

- Plaintiff tactics and corresponding defense approaches

- Judicial mechanisms for dismissing inadequate scienter claims

- Corporate scienter attribution and group pleading complexities

Understanding Scienter: The Mental State Standard That Determines Securities Fraud Liability

- Scienter: Stands as the most critical—and most contested—element in securities fraud litigation under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act.

- Mental State: This mental state requirement creates the fundamental distinction between actionable securities fraud and ordinary business disappointments that trigger stock price declines.

Scienter Definitions: Supreme Court Precedent and Legal Framework

- Mental State Standard: The Supreme Court established in Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd., 551 U.S. 308 (2007) that scienter represents “a mental state embracing intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud”. This definition creates the essential barrier separating securities fraud from negligent misstatements or innocent business errors that cause investor losses.

- Intent-Based Liability: The landmark 1976 decision in Ernst v. Hochfelder, 425 U.S. 185 (1976) definitively established that Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 require intent-based liability rather than mere negligence. This foundational ruling eliminated the possibility that companies could face securities fraud liability for unintentional mistakes in financial reporting or business communications.

- Six-Element Framework: Securities fraud claims demand proof of multiple interconnected elements that create substantial pleading challenges:

- Material misrepresentation or omission in corporate communications

- Scienter demonstrating fraudulent intent or severe recklessness

- Connection between alleged fraud and securities transactions

- Investor reliance on the misleading statements

- Demonstrable damages from the alleged deception

- Loss causation linking the fraud to investor harm

- Pleading Challenges: Scienter represents the most difficult element to satisfy in securities fraud litigation.

- Dismissal: Courts frequently grant motions to dismiss based solely on inadequate scienter allegations, making this requirement the primary battleground for early case resolution.

Recklessness Standards: Circuit Court Approaches to Mental State Requirements

- Unresolved Supreme Court Question: The Supreme Court has reserved judgment three times regarding whether recklessness satisfies the scienter requirement for Section 10(b) liability, creating uncertainty across federal circuits. This unresolved issue has produced varying standards that affect litigation strategy and case outcomes.

- Circuit Court Consensus: Most federal circuits accept that recklessness can establish scienter when the conduct reaches sufficient severity. The First Circuit requires “highly unreasonable omission, involving not merely simple, or even inexcusable negligence, but an extreme departure from the standards of ordinary care”.

- Knowledge-Based Recklessness: The Second Circuit recognizes scienter when defendants “failed to review or check information that they had a duty to monitor, or ignored obvious signs of fraud“. Companies that possess information contradicting their public statements may establish the requisite mental state through willful blindness or conscious disregard.

- Severe Recklessness Threshold: Courts distinguish between ordinary recklessness and the “severe recklessness” necessary for securities fraud liability. This heightened standard ensures that only conduct approaching intentional fraud triggers Section 10(b) liability, preventing the statute from becoming a general negligence provision for business disappointments.

CIRCUIT-BY-CIRCUIT PLEADING STANDARD FOR SCIENTER

Circuit | Summary of Pleading Standard | Key Cases | Notes and Circuit Splits |

First Circuit | Requires strong inferenceof scienter under PSLRA standards. Accepts allegations of motive and opportunity combined with strong circumstantial evidence. | Greenberg v. Crossroads Systems(2020); In re Biogen Securities Litigation(2019) | Aligns with majority circuits requiring “strong inference” but more lenient on motive and opportunity allegations than some circuits. |

Second Circuit | Applies “strong inference”standard with emphasis on holistic analysis. Requires inference of scienter to be at least as compelling as any opposing inference. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights(2007); ATSI Communications v. Shaar Fund(2021) | Leading circuiton scienter interpretation post-Tellabs. Emphasizes comparative plausibility of inferences. |

Third Circuit | Follows Tellabsstandard requiring strong inference that is cogent and compelling. Accepts core operations doctrine in limited circumstances. | In re Hertz Global Holdings Securities Litigation(2020); City of Edinburgh Council v. Pfizer(2014) | Circuit spliton core operations doctrine – more restrictive than some circuits but accepts it in narrow circumstances. |

Fourth Circuit | Requires “strong inference”with particular emphasis on contemporaneous evidence. Skeptical of pure motive and opportunity allegations. | Teachers’ Retirement System v. Hunter(2019); Cozzarelli v. Inspire Pharmaceuticals(2008) | More demanding standard for motive and opportunity allegations compared to First and Ninth Circuits. |

Fifth Circuit | Applies strict “strong inference”standard. Requires particularized factssuggesting deliberate recklessness or actual knowledge. | ABC Arbitrage Plaintiffs Group v. Tchuruk(2002); Rosenzweig v. Azurix Corp.(2003) | Most restrictive circuit on scienter pleading. Rarely accepts motive and opportunity alone. |

Sixth Circuit | Follows Tellabswith moderate application. Accepts core operations doctrineand strong circumstantial evidence. | In re Omnicare Securities Litigation(2014); Helwig v. Vencor(2001) | Middle-ground approach – less restrictive than Fifth Circuit but more demanding than Ninth Circuit. |

Seventh Circuit | Home of Tellabs decision. Requires holistic analysis where inference of scienter must be at least as compelling as competing inferences. | Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights(2007); Higginbotham v. Baxter International(2007) | Authoritative circuit post-Tellabs. Emphasizes comparative plausibility standard. |

Eighth Circuit | Applies “strong inference”standard with acceptance of core operations doctrine. Moderate approach to motive and opportunity. | In re K-tel International Securities Litigation(2002); In re Navarre Corp. Securities Litigation(2002) | Generally follows mainstream approach without significant departures from other circuits. |

Ninth Circuit | Most lenient circuiton scienter pleading. Readily accepts motive and opportunityallegations and core operations doctrine. | In re Oracle Corp. Securities Litigation(2010); Zucco Partners v. Digimarc Corp.(2009) | Major circuit split- significantly more plaintiff-friendly than Fifth, Second, and Fourth Circuits. |

Tenth Circuit | Requires “strong inference”with emphasis on deliberate recklessness. Moderate acceptance of circumstantial evidence. | City of Philadelphia v. Fleming Cos.(2001); Adams v. Kinder-Morgan(2003) | Follows mainstream approach similar to Sixth and Eighth Circuits. |

Eleventh Circuit | Applies strict “strong inference”standard. Requires particularized allegationsof actual knowledge or deliberate recklessness. | Bryant v. Avado Brands(1999); In re Stac Electronics Securities Litigation(1999) | Restrictive approach similar to Fifth Circuit. Skeptical of pure motive and opportunity theories. |

D.C. Circuit | Follows Tellabs standard with rigorous analysis. Emphasizes need for contemporaneous evidenceof scienter. | Jaffee v. Crane Co.(2016); Longman v. Food Lion(1999) | Sophisticated analysis reflecting complex securities cases. Generally restrictive but fact-specific. |

Federal Circuit | Limited securities jurisdiction. When applicable, follows Tellabs standard with emphasis on technical complexity considerations. | In re Seagate Technology Securities Litigation(2008) | Rarely handles securities cases. Defers to regional circuits on most scienter issues. |

Scienter in Securities Class Actions: Pleading Requirements and Strategic Frameworks

Central Litigation Battleground: Scienter determines the survival of securities class action litigation at the motion to dismiss stage, where defendants challenge case viability before expensive discovery begins. The PSLRA requires complaints to “state with particularity facts giving rise to a strong inference that the defendant acted with the required state of mind”.

Tellabs Analysis Framework: The Supreme Court’s Tellabsdecision established a three-part analytical structure that courts must follow when evaluating scienter adequacy:

First, courts accept all factual allegations as true while rejecting legal conclusions disguised as facts. Second, judges consider the entire complaint holistically rather than examining allegations in isolation. Third, courts conduct comparative assessment determining whether “a reasonable person would deem the inference of scienter at least as compelling as any opposing inference” of innocent conduct.

Dual Pleading Strategies: Plaintiffs establish scienter through two primary approaches that reflect different litigation philosophies. Motive and opportunity allegations demonstrate defendants benefited “in a concrete and personal way” from alleged fraud. Circumstantial evidence approaches focus on conscious misbehavior or reckless conduct that suggests fraudulent intent.

Corporate Scienter Complexity: Corporate defendants present unique challenges because corporations act only through human agents, requiring courts to develop theories of “corporate mind”. Plaintiffs typically plead corporate scienter by establishing individual scienter against corporate officers who made challenged statements, then imputing that mental state to the corporate entity.

Theoretical Underdevelopment: Scienter pleading remains “one of the greatly under-theorized subjects in all of securities litigation” despite determining which cases survive preliminary challenges. This theoretical gap creates practical uncertainties for both plaintiffs attempting to satisfy pleading requirements and defendants seeking to challenge inadequate allegations.

PSLRA Statutory Requirements: The Foundation of Modern Securities Litigation Defense

- Statutory Framework: The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (PSLRA) fundamentally transformed securities fraud litigation by establishing formidable pleading barriers that eliminate frivolous lawsuits while creating powerful early dismissal mechanisms for defendants.

- Congressional Intent: These requirements serve as essential safeguards against the systematic abuse that previously plagued securities markets, where plaintiffs routinely filed lawsuits following any significant stock price decline without regard to actual culpability.

PRE-AND POST-PSLRA STANDARDS FOR SECURITIES FRAUD LITIGATION

Feature | Pre-PSLRA Standard | Post-PSLRA Standard |

Motion to dismiss | Based on “notice pleading” (Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(a)), making it easier for plaintiffs to survive motions to dismiss. This often led to settlements to avoid costly litigation. | Requires satisfying PSLRA’s heightened pleading standards and the “plausibility” standard from Twombly and Iqbal. Failure to plead with particularity on any element can result in dismissal. |

Pleading | “Notice pleading” was generally sufficient, though fraud claims under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b) required particularity for the circumstances of fraud, but intent could be alleged generally. | Each misleading statement must be stated with particularity, explaining why it was misleading. Facts supporting beliefs in claims based on “information and belief” must also be stated with particularity. |

Scienter | Pleaded broadly; the “motive and opportunity” test was often sufficient to infer intent. | Requires alleging facts creating a “strong inference” of fraudulent intent, which must be at least as compelling as any opposing inference of non-fraudulent intent, as clarified in Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd.. |

Loss causation | Not a significant pleading hurdle, often assumed if a plaintiff bought at an inflated price. | Requires pleading facts showing the fraud caused the economic loss, often by linking a corrective disclosure to a stock price drop. Dura Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Broudo affirmed this. |

Discovery | Could proceed while a motion to dismiss was pending. | Automatically stayed during a motion to dismiss. |

Safe harbor for forward-looking statements | No statutory protection. | Protects certain forward-looking statements if accompanied by “meaningful cautionary statements”. |

Lead plaintiff selection | Often the first investor to file. | Court selects based on a “rebuttable presumption” that the investor with the largest financial interest is the most adequate. |

Liability standard | For non-knowing violations, liability was joint and several. | For non-knowing violations, liability is proportionate; joint and several liability applies only if a jury finds knowing violation. |

Mandatory sanctions | Available under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11, but judges were often reluctant to impose them. | Requires judges to review for abusive conduct |

Heightened Pleading Standards under 15 U.S.C. § 78u-4(b)

- Precision Requirements: Section 78u-4(b) demands extraordinary specificity that exceeds traditional fraud pleading standards.

- Securities fraud complaints must satisfy four critical statutory mandates:

- Statement Identification: Specify each allegedly misleading statement with precision

- Misleading Nature: Explain specific reasons why each statement constitutes deception

- Factual Foundation: State with particularity facts supporting all allegations made on information and belief

- Mental State Proof: State with particularity facts giving rise to a strong inference that the defendant acted with the required state of mind

- Abusive Practice Prevention: Congress enacted these standards to eliminate “abusive practices committed in private securities litigation” including “the routine filing of lawsuits against issuers of securities and others whenever there is a significant change in an issuer’s stock price, without regard to any underlying culpability”.

- Immediate Consequences: Complaints failing these statutory requirements face automatic dismissal upon defendants’ motion. This framework forces plaintiffs to articulate coherent theories of deception before imposing discovery costs on defendants.

Tellabs Framework: Supreme Court Guidance on Strong Inference

- Landmark Decision: The Supreme Court’s Tellabsdecision established the definitive standard for scienter pleading under the PSLRA. The Court rejected weaker inference standards, declaring that strong inference must be “more than merely plausible or reasonable—it must be cogent and at least as compelling as any opposing inference of nonfraudulent intent“.

- Three-Step Judicial Analysis:

- Step One: Accept all factual allegations as true during motion evaluation

- Step Two: Examine whether “all of the facts alleged, taken collectively, give rise to a strong inference of scienter“

- Step Three: Conduct comparative assessment, “taking into account plausible opposing inferences“

- Balanced Approach: The Supreme Court specifically rejected the Seventh Circuit’s plaintiff-favorable approach, mandating that courts weigh both culpable and non-culpable inferences. Omissions and ambiguities count against scienter inferences, though courts must evaluate allegations holistically.

- Circuit Division: A significant circuit split exists regarding internal company reports. The First and Ninth Circuits permit complaints without specific document contents, while five circuits—Second, Third, Fifth, Seventh, and Tenth—require detailed allegations about document contents.

Rule 9(b) versus PSLRA Standards: Dual Compliance Requirements

- Overlapping Obligations: Securities fraud complaints must simultaneously satisfy Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b) and the PSLRA‘s enhanced requirements. Rule 9(b) mandates pleading “with particularity”, though it permits general allegations regarding mental state.

- PSLRA Enhancement: The PSLRA surpasses Rule 9(b) by requiring:

- Particular facts supporting all fraud allegations

- Strong scienter inference at least as compelling as opposing inferences

- Historical Evolution: Prior to the PSLRA, the Second Circuit maintained the most stringent pleading standards. Plaintiffs could establish fraudulent intent through “alleging facts establishing a motive to commit fraud and an opportunity to do so” or by “alleging facts constituting circumstantial evidence of either reckless or conscious behavior”.

- Modern Application: Courts now recognize that motive allegations alone prove insufficient without holistic complaint assessment. This comprehensive framework has created “a significant bar to litigation”, ensuring only meritorious securities fraud claims survive preliminary challenges and proceed to costly discovery proceedings.

Scienter Evaluation: Motive, Opportunity, and Conscious Misbehavior Standards

- Judicial Analysis: Courts evaluating scienter allegations employ distinct analytical frameworks to determine whether plaintiffs have satisfied the heightened pleading requirements established by the PSLRA.

- Battleground: These evaluation standards create the battleground where securities fraud litigation cases succeed or fail at the motion to dismiss stage.

Motive and Opportunity Framework: Second Circuit Standards

- Second Circuit Approach: The Second Circuit recognizes Motive and Opportunity as an independent pathway to establish scienter in securities fraud cases.

- Second Circuit Frameword: This framework demands that plaintiffs demonstrate defendants benefited “in a concrete and personal way” from the alleged fraudulent conduct. Generalized profit-seeking allegations prove insufficient under this rigorous standard.

- Insufficient Motive Allegations:

- Executive Compensation: Desire to increase standard executive compensation packages

- Position Retention: General desire to maintain corporate positions

- Stock Options: Receipt of routine stock options and incentive payments

- Commonplace Motivations: District courts recognize that “in today’s corporate environment, nearly all executives are compensated with stock options and incentive bonuses,” rendering these motivations too ordinary to suggest fraudulent intent.

- Standard Fails: Standard desires to maintain stock prices or corporate profitability fail to establish the requisite scienter without additional compelling factors.

- Adequate Motive Pleading:

- Insider Trading: “Unusual” stock sales at artificially inflated prices during fraud periods

- Concrete financial benefits: Direct financial advantages tied specifically to alleged misrepresentations

- Third-Party Incentives: Service providers seeking to retain substantial clients or reduce affiliate risk exposure

- Post-Tellabs Application: The Second Circuit maintains this motive and opportunity framework following the Supreme Court’s Tellabsdecision, asserting compatibility with PSLRA requirements.

Conscious Misbehavior Standards: Circumstantial Evidence Requirements

- Alternative Pleading Path: Plaintiffs may establish scienter through strong circumstantial evidence of conscious misbehavior or recklessness when motive and opportunity allegations prove insufficient. This approach focuses on defendants’ knowledge of contradictory information rather than financial incentives.

- Circumstantial Evidence Categories:

- Trading Patterns: Insider trading timing and unusual sale volumes

- Access to Information: Defendants’ positions providing access to contradictory data

- Internal Reports: Existence of adverse internal documentation

- Executive Departures: Resignations occurring during alleged fraud periods

- Accounting Irregularities: GAAP violations and accounting restatements

- Inadequate Allegations: Courts consistently reject generalized claims regarding adverse internal reports without specific content details. GAAP violations or accounting restatements alone cannot establish fraudulent intent, nor can executive resignations without evidence connecting departures to alleged fraud schemes.

Circuit Split Analysis: Jurisdictional Variations in Scienter Standards

- Divergent Approaches: Significant variations exist among federal circuits regarding scienter pleading standards as noted in the chart above. The Second and Third Circuits permit motive and opportunity allegations, while the Ninth Circuit requires evidence indicating “a degree of recklessness that strongly suggests actual intent”.

- Post-Tellabs Circuit Positions: Most circuits now reject motive and opportunity as independently sufficient for establishing strong inference of scienter:

- First Circuit: “Evidence of motive and opportunity to commit fraud does not, of itself, constitute scienter“

- Fifth, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuits: Similarly reject motive and opportunity as independently adequate

- Second Circuit: Maintains strong inference through motive and opportunity when allegations demonstrate concrete personal benefit

- Corporate Scienter Variations: The Sixth Circuit employs a “middle approach” for corporate scienter through three categories of individuals whose mental states establish requisite intent. The Second Circuit requires plaintiffs to plead “facts that give rise to a strong inference that someone whose intent could be imputed to the corporation acted with the requisite scienter“.

- Strategic Implications: These jurisdictional differences create tactical considerations for both plaintiffs and defendants when evaluating scienter allegations in securities fraud cases across different federal circuits.

Plaintiff Tactics and Defense Strategies: The Battle Over Scienter Allegations

- Tactical Warfare: Securities fraud litigation represents sophisticated legal combat where plaintiffs employ established strategies to construct scienter allegations while defendants deploy corresponding countermeasures to defeat these claims before costly discovery begins.

- Strategic Importance: Understanding these tactical approaches proves essential for practitioners navigating securities fraud class actions, as the outcome of scienter battles determines which cases survive preliminary challenges and proceed to expensive litigation phases .

Confidential Witnesses: Insider Sources and Credibility Challenges

- Standard Practice: Confidential witnesses have become ubiquitous features in securities fraud complaints, reflecting the heightened pleading requirements imposed by the PSLRA . These sources—typically former employees of defendant companies—provide insider allegations designed to bolster scienter claims without access to discovery materials.

- Judicial Evaluation: Courts examine confidential witness allegations through rigorous analytical frameworks:

- Specificity and detail level provided by the sources

- Basis of knowledge and source reliability

- Corroborative nature of other factual allegations

- Coherence and plausibility of witness statements

- Hard Look Standard: Federal judges apply a “hard look” standard to these allegations, assessing whether “a person in the position occupied by the source would possess the information alleged.”

- Inheriently Unreliable: Courts frequently discount confidential witness claims due to inherent credibility concerns and the absence of cross-examination opportunities.

- Credibility Problems: Confidential witnesses often lack firsthand knowledge of the statements attributed to them or may be motivated by spite rather than accurate information . Defense strategies focus on demonstrating that witnesses lack personal knowledge of their attributed statements, while plaintiff counsel must confirm witness statements before filing and notify witnesses of their intended use in complaints.

Insider Trading Patterns: Timing and Trading Plan Defenses

- Circumstantial Evidence: Corporate insider stock sales frequently serve as circumstantial evidence of scienter in securities fraud cases, with courts evaluating multiple factors:

- Volume and percentage of shares sold by corporate insiders

- Timing of sales relative to allegedly misleading public statements

- Historical trading patterns of the individuals involved

- Trading Plan Defense: Defendants can effectively undermine these allegations by demonstrating that stock sales occurred pursuant to pre-established Rule 10b5-1 trading plans. Courts have stated definitively that “sales conducted pursuant to a 10b5-1 trading plan… could not be timed suspiciously” , creating powerful defensive tools against insider trading allegations.

Adverse Internal Reports and Core Operations Theory

- Common Allegations: Plaintiffs routinely allege that defendants possessed access to negative internal reports contradicting their public statements, yet these claims frequently fail due to insufficient specificity . Merely claiming the existence of adverse reports without particulars regarding content fails to support scienter inferences under heightened PSLRA standards.

- Core Operations Theory: The core operations doctrine argues that senior management must have known about fraud involving the company’s primary business activities . This theory typically proves insufficient to establish scienter without substantial additional supporting evidence connecting management knowledge to specific misrepresentations.

GAAP Violations: Insufficient Standing Alone

- Accounting Fraud Context: Allegations of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles violations remain standard components in accounting fraud cases, yet courts consistently hold that GAAP violations alone cannot support scienter inferences.

- Tenth Circuit Standard: The Tenth Circuit established that such allegations may suffice only when “coupled with evidence that the violations or irregularities were the result of the defendant’s fraudulent intent to mislead investors” . Successful pleading requires particularized facts demonstrating fraudulent intent alongside accounting irregularities.

- Defense Advantage: Defendants can effectively challenge complaints relying solely on alleged accounting improprieties without additional evidence of intent to deceive, creating substantial barriers for plaintiffs attempting to proceed on GAAP violations alone .

Judicial Tools for Dismissing Scienter Claims

- Federal courts provide defendants with powerful mechanisms to challenge inadequate scienter allegations before courts permit costly discovery proceedings or trial litigation in securities fraud cases.

- Rule 12(b)(6) Motions to Dismiss

- Rule 12(b)(6) motions: Serve as the primary weapon for eliminating deficient scienter allegations at the pleading stage. These motions challenge whether plaintiffs’ complaints state valid legal claims even when all factual allegations are accepted as true.

- Judicial Analysis Requirements:

- Complaints must “state with particularity” facts establishing a strong inference of scienter

- The inference must prove “cogent and at least as compelling as any opposing inference of nonfraudulent intent”

- Allegations require holistic evaluation to determine whether they establish the requisite mental state

- Dismissal Success Rates: Scienter deficiencies account for 53% to 65% of successful dismissal motions in securities fraud litigation. Courts accept factual allegations as true but reject legal conclusions disguised as factual statements during this analysis.

- Strategic Advantage: These motions eliminate weak cases before defendants face the substantial costs associated with securities class action discovery and trial preparation.

Extrinsic Documents: Undermining Scienter Through External Evidence

- Courts may examine materials beyond the complaint without converting dismissal motions into summary judgment proceedings through established legal mechanisms.

- Judicial Notice permits consideration of facts not subject to reasonable dispute when they are:

- Generally known within the court’s territorial jurisdiction

- Capable of determination from sources of unquestionable accuracy

- Incorporation by Reference allows courts to examine documents that are:

- Referenced directly in the complaint

- Central to plaintiff’s legal claims

- Of unquestioned authenticity by either party

- Supreme Court Authority: The Court has explicitly authorized consideration of “relevant extrinsic materials” when determining whether allegations create strong inferences of scienter. Defendants should examine all documents referenced in complaints alongside documents implicitly relied upon for scienter allegations.

PSLRA Automatic Discovery Stay: Preventing Coercive Settlements

Statutory Protection: The PSLRA mandates that “all discovery and other proceedings shall be stayed during the pendency of any motion to dismiss“. This automatic stay provision creates essential defense protection against abusive litigation tactics.

Discovery Abuse Prevention:

- Securities class actions discovery often constitutes expensive “fishing expeditions”

- Discovery costs frequently coerce defendants to settle meritless cases

- The stay prevents plaintiffs from using early discovery pressure to force settlements

Scope and Limitations: The discovery stay applies to “any private action” under securities laws, though state courts remain divided regarding its application to state court proceedings. Courts may permit discovery only when “particularized discovery is necessary to preserve evidence or to prevent undue prejudice”.

Congressional Intent: This mechanism ensures “discovery should be permitted in securities class actions only after the court has sustained the legal sufficiency of the complaint”.

Corporate Scienter Attribution: Group Pleading and Entity Liability Complexities

- Corporate Scienter: Presents formidable challenges in securities fraud litigation because corporations function exclusively through human agents, creating complex questions about mental state attribution that significantly impact pleading strategies and liability determinations.

- Attribution Framework: Courts must resolve how to assign fraudulent intent to corporate entities that lack independent consciousness, requiring sophisticated legal theories to connect individual knowledge with corporate liability .

Three-Tiered Approach to Corporate Mental State Attribution

- Judicial Frameworks: Federal circuits employ distinct methodologies for determining when individual scienter establishes corporate liability in securities fraud cases.

- Traditional Approach: Requires scienter from the specific individual who made the challenged statement, creating narrow liability that protects corporations when non-culpable officers issue public communications.

- Middle Approach: Permits scienter attribution from individuals who prepared or approved statements, expanding potential liability to include behind-the-scenes decision-makers who influence corporate disclosures.

- Broad Approach: Allows aggregation of knowledge from different corporate agents, creating the most expansive theory of corporate liability by combining various employees’ mental states.

- Second Circuit Standards: The Second Circuit demands pleading “facts that give rise to a strong inference that someone whose intent could be imputed to the corporation acted with the requisite scienter“ . Corporate defendants benefit when plaintiffs cannot establish “connective tissue” linking knowledgeable lower-level employees to actual corporate disclosures.

Group Pleading Doctrine Post-Janus Legal Uncertainty

- Historical Framework: The group pleading doctrine previously permitted attribution of statements in group-published documents to corporate insiders involved in daily operations, simplifying scienter pleading for securities plaintiffs.

- Janus Disruption: The Supreme Court’s 2011 Janusdecision created substantial uncertainty by establishing that only the “maker” with “ultimate authority” over a statement faces liability, potentially undermining traditional group pleading approaches.

- Circuit Division: Courts remain split on Janus implications:

- Courts rejecting group pleading argue Janus prohibits attribution absent direct statement authority

- Courts preserving group pleading distinguish Janus as addressing third-party liability rather than internal corporate attribution

Collective Scienter Theory: Circuit-Level Strategic Variations

- Ninth Circuit Rejection: The Ninth Circuit rejected “collective scienter” in Glazer Capital Management, requiring individual rather than aggregated mental state proof.

- Sixth Circuit Compromise: The Sixth Circuit adopted a middle approach identifying three categories of individuals whose knowledge can establish corporate scienter, providing structured attribution guidelines.

- Second Circuit Precision: The Second Circuit requires specific “connective tissue” between employees with knowledge and corporate statements, demanding particularized pleading that connects individual awareness to corporate communications

- Defense Strategy: The most effective corporate scienter defense demonstrates lack of connection between knowledgeable employees and those responsible for corporate disclosures, severing the attribution chain that plaintiffs must establish .

Scienter Pleading Mastery: Essential Knowledge for Securities Litigation Success

Securities fraud litigation creates a demanding legal environment where scienter pleading requirements determine case outcomes at the earliest procedural stages. This analysis demonstrates how the PSLRA fundamentally altered the litigation landscape by establishing rigorous standards that separate meritorious claims from opportunistic lawsuits targeting routine business disappointments.

Formidable Standards: The heightened pleading requirements impose substantial obstacles for plaintiffs while providing defendants with powerful dismissal mechanisms. Courts must evaluate whether complaints establish fraudulent intent that satisfies the demanding “strong inference” standard—a mental state embracing intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud that exceeds mere negligence or business misjudgments.

Strategic Considerations: Effective securities fraud litigation strategy requires understanding multiple analytical frameworks:

- Circuit variations create different standards for motive and opportunity allegations, with some jurisdictions accepting concrete personal benefit theories while others demand stronger recklessness evidence

- Plaintiff approaches typically involve confidential witness testimony, insider trading allegations, and adverse internal report claims that often fail without specific supporting details

- Defense tactics focus on challenging allegation specificity through Rule 12(b)(6) motions while utilizing PSLRA discovery stay provisions to prevent costly settlement pressure

- Corporate scienter attribution remains particularly complex, requiring “connective tissue” between knowledgeable employees and actual corporate disclosures

Supreme Court Clarification: The anticipated Supreme Court decision promises to resolve persistent circuit splits that have created uncertainty in scienter evaluation standards. However, the Supreme Court subsequented dismissed in the appeal as “improvidently granted.”

Practical Application: Understanding these legal frameworks enables practitioners to analyze complaint adequacy, identify procedural opportunities, and develop jurisdiction-specific litigation strategies. Corporate officers facing potential liability benefit from recognizing how courts evaluate fraudulent intent allegations, while plaintiff attorneys must appreciate the substantial evidentiary burdens required to survive preliminary challenges.

Market Integrity: These rigorous standards serve essential functions in maintaining securities market confidence by preventing frivolous litigation while ensuring that genuine fraud cases proceed to discovery and potential resolution. The balance between investor protection and litigation abuse prevention continues to evolve through judicial interpretation and legislative refinement.

Key Takeaways

Understanding scienter requirements is crucial for navigating securities fraud litigation effectively under the PSLRA’s heightened standards.

• Scienter requires “intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud” – mere negligence isn’t enough for Section 10(b) claims

• PSLRA demands “strong inference” of scienter that’s “at least as compelling as any opposing inference” per Tellabs framework

• Motive and opportunity alone typically insufficient – courts require concrete personal benefit beyond standard executive compensation

• PSLRA’s automatic discovery stay prevents costly fishing expeditions, forcing early resolution of scienter adequacy

• Corporate scienter attribution requires “connective tissue” linking knowledgeable employees to actual corporate disclosures

The Supreme Court’s upcoming decision on PSLRA pleading standards will likely resolve existing circuit splits and bring uniformity to securities fraud litigation. Success in these cases hinges on understanding jurisdiction-specific approaches to scienter evaluation and leveraging procedural tools like Rule 12(b)(6) motions effectively.

FAQs

Q1. What is scienter in securities fraud litigation? Scienter refers to the mental state of intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud in securities fraud cases. It’s a critical element that plaintiffs must prove to establish liability under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act.

Q2. How does the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) affect pleading requirements for scienter? The PSLRA imposes heightened pleading standards, requiring plaintiffs to state with particularity facts giving rise to a strong inference of scienter. This standard is more stringent than traditional fraud claims and aims to prevent frivolous lawsuits.

Q3. Can recklessness satisfy the scienter requirement in securities fraud cases? While the Supreme Court hasn’t definitively ruled on this, most circuit courts accept that severe recklessness can establish scienter. This typically involves conduct that represents an extreme departure from standards of ordinary care.

Q4. What are some common ways plaintiffs try to demonstrate scienter? Plaintiffs often allege insider trading, the existence of contradictory internal reports, accounting violations, or use confidential witnesses. They may also argue that fraud involved the company’s core operations, implying executives must have known about it.

Q5. How can defendants challenge scienter allegations in securities fraud cases? Defendants can file motions to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6), arguing that even if alleged facts are true, they don’t establish a strong inference of scienter. They can also use the PSLRA’s automatic discovery stay to prevent costly “fishing expeditions” before the legal sufficiency of the complaint is determined.

Contact Timothy L. Miles Today for a Free Case Evaluation

If you suffered substantial losses and wish to serve as lead plaintiff in a securities class action, or have questions about securities class action settlements, or just general questions about your rights as a shareholder, please contact attorney Timothy L. Miles of the Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles, at no cost, by calling 855/846-6529 or via e-mail at [email protected]. (24/7/365).

Timothy L. Miles, Esq.

Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles

Tapestry at Brentwood Town Center

300 Centerview Dr. #247

Mailbox #1091

Brentwood,TN 37027

Phone: (855) Tim-MLaw (855-846-6529)

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.classactionlawyertn.com

Facebook Linkedin Pinterest youtube

Visit Our Extensive Investor Hub: Learning for Informed Investors