Introduction and Summary of Falsifying Financial Statements

- Falsifying Financial Statements: Is a criminal act of intentionally misrepresenting a company’s financial records to deceive stakeholders, such as investors, creditors, and regulators.

- False Financial Healh: The fraud creates a false picture of the company’s financial health, often to increase stock prices, secure favorable loans, or meet performance targets.

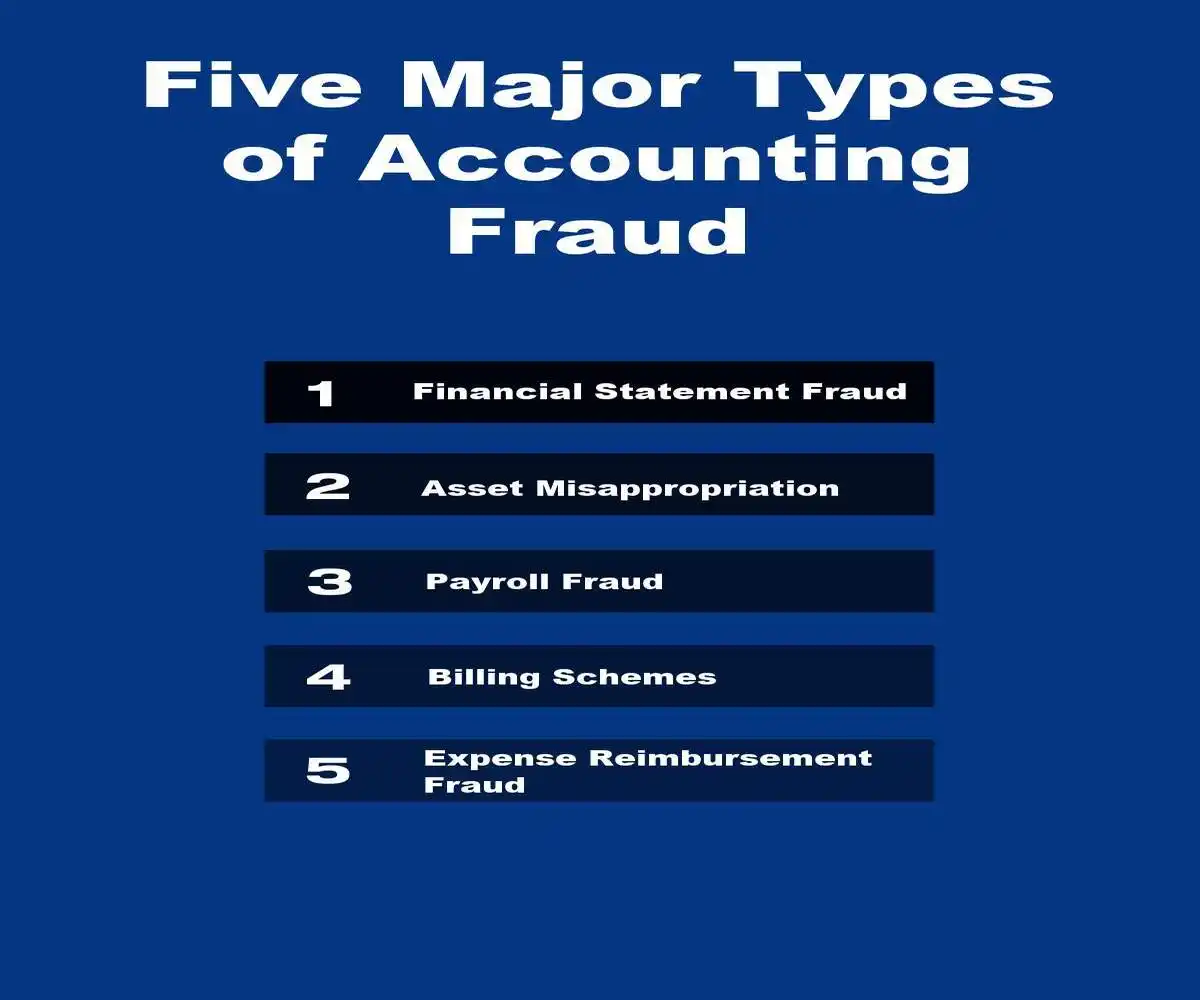

Common methods

- Perpetrators of financial statement fraud use various techniques, including:

- Inflating revenue: Recording sales before they are earned or creating fictitious sales and invoices to overstate a company’s income.

- Manipulating expenses: Deferring or understating expenses, or improperly capitalizing costs (recording them as assets) to artificially inflate profits.

- Concealing liabilities: Hiding debts or financial obligations, sometimes using off-balance-sheet entities, to make a company’s financial position appear stronger.

- Overstating assets: Inflating the value of assets like inventory or property to make the company seem more financially stable.

- Timing differences: Shifting revenues or expenses between accounting periods to meet earnings targets or smooth profits.

Motives for falsification

- Executives or managers may falsify financial statements for several reasons:

- Pressure to meet expectations: Intense pressure to meet quarterly earnings goals or projections set by Wall Street analysts.

- Executive compensation: Achieving performance targets that trigger large bonuses or incentive-based compensation.

- Attracting investors and lenders: Making the company appear more financially attractive to secure investments or favorable credit terms.

- Boosting stock prices: Artificially inflating the company’s stock price for personal gain or to prevent a market value decrease.

Legal and corporate consequences

- The repercussions for individuals and companies involved in falsifying financial statements can be severe and far-reaching.

- Legal penalties: Individuals can face criminal charges, including hefty fines and lengthy prison sentences. Regulators like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) can also bring civil and criminal charges.

- Civil lawsuits: Shareholders, investors, and other parties who suffered financial harm can file private lawsuits against the company and responsible individuals to recover damages.

- Loss of reputation: A fraud scandal severely damages a company’s reputation and credibility, making it difficult to regain the trust of customers, investors, and the public.

- Financial collapse: In many infamous cases, such as the Enron and WorldCom scandals, sustained fraudulent activities ultimately led to corporate bankruptcy and collapse.

- Regulatory reforms: Major frauds have prompted legislative action, most notably the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002. This law requires CEOs and CFOs to personally certify the accuracy of financial reports and imposes severe penalties for falsification.

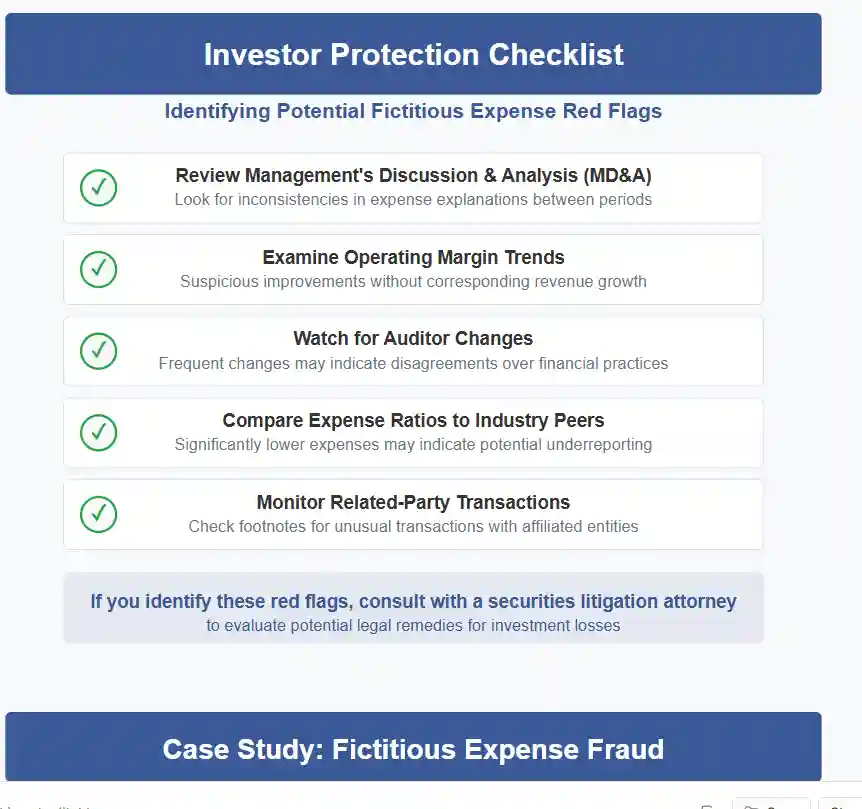

Red flags and prevention

- Several indicators, or “red flags,” can suggest that financial statements may be fraudulent:

- Inconsistent growth: Rapid or unusual revenue growth that is out of line with industry trends or economic conditions.

- Lack of cash flow: Significant discrepancies between a company’s reported profits and its actual cash flow.

- Frequent auditor changes: Sudden changes in auditing firms or a high turnover of key accounting personnel.

- Restated results: Frequent restatements of prior financial results.

- Excessive reliance on non-recurring revenue:

- Using one-off gains to meet financial targets.

- To prevent financial statement fraud, companies should implement strong internal controls, foster an ethical corporate culture, and engage in regular, independent audits.

Falsifying Financial Statements: Fraud Detection, Prevention, and Legal Consequences

- Falsifying financial statements: Represents one of the most devastating forms of corporate misconduct in modern financial markets, serving as a catalyst for numerous securities class action lawsuits and regulatory enforcement actions.

- Deceptive Scheme: This deceptive practice undermines the fundamental trust that investors place in corporate financial reporting, creating a dangerous web of deception that can devastate market confidence and trigger costly securities litigation.

Common Methods of Falsifying Financial Statements

- Complex Accounting Schemes: Falsifying financial statements is a sophisticated deceptive practice that manifests through multiple interconnected schemes, each designed to mislead stakeholders about a company’s true financial performance.

- Intentional Fraud: These fraudulent activities extend far beyond simple number manipulation, involving complex accounting maneuvers that exploit regulatory gaps and exploit weaknesses in internal controls.

- Revenue inflation: This remains the most prevalent method of financial statement fraud.

Highly Sophisticated Accounting Schemes

- Sophisticated Fraud: Companies engage in this practice through various sophisticated techniques, including the creation of fictitious sales transactions, premature revenue recognition that violates established accounting principles, and channel stuffing operations where excessive inventory is pushed to distributors beyond their actual sales capacity.

- False Financial Health: These tactics create an artificial illusion of robust financial health, deliberately misleading investors and analysts who rely on accurate financial data for investment decisions.

- The WorldCom Scandal: This case exemplifies the devastating consequences of revenue manipulation.

- Artifically Inflating Revenues: The telecommunications giant artificially inflated revenues by improperly capitalizing operating expenses as capital expenditures, creating the false appearance of profitability while hiding billions in actual losses.

- Securities Litigation Trigger: When the fraud was revealed, it triggered one of the largest securities class action settlements in history, ultimately resulting in $6.1 billion in investor recoveries.

Systematically Manipulating Expenses

- Expense manipulation: Represents another common tactic where companies systematically understate their true operational costs.

- Fake Reserves: This practice involves delaying the recognition of legitimate business expenses, improperly capitalizing costs that should be immediately expensed, or creating fictitious reserves that can be reversed in future periods to artificially boost earnings.

- Compliance Violations: Such manipulations directly violate regulatory compliance requirements under Sarbanes-Oxley Act provisions.

Intentionally Manipulating the Valuation of Assets

- Asset valuation manipulation involves the deliberate misrepresentation of asset values on corporate balance sheets.

- Deliberately Inflating Asset Values: Companies engaging in this practice often overstate inventory values, improperly value investment securities, inflate property and equipment appraisals, or fail to recognize impairment losses when asset values decline.

- Securities Litigation Trigger: These manipulations can significantly distort a company’s financial position, leading to misguided investment decisions and subsequent securities litigation when the truth emerges.

- The Enron collapse demonstrates the extreme consequences of asset valuation fraud:

- Concealing True Financial Health: The energy giant used special purpose entities to hide debt and inflate asset values, creating an elaborate scheme that concealed the company’s true financial condition.

- Led to Significant Reforms: The eventual disclosure of these practices led to the company’s bankruptcy, massive investor losses, and fundamental changes in corporate governance requirements.

The Devastating Impact of Falsified Financial Statements on Investors

- Deadly Consequences: The consequences of falsified financial statements extend far beyond immediate financial losses, creating a cascade of devastating effects that ripple through entire market sectors. When companies manipulate financial data, they fundamentally breach the trust relationship with investors, creating false premises for investment decisions that can result in catastrophic financial losses when corrective disclosures eventually emerge.

- Securities class actions: Frequently arise when investors discover they have been misled by fraudulent financial reporting. These legal proceedings provide a mechanism for recovering losses, but the litigation process often extends for years, creating additional uncertainty for affected investors. The SEC enforcement actions that typically accompany major fraud cases can result in substantial penalties for companies, further diminishing shareholder value.

- The psychological impact on investors cannot be understated. The betrayal of trust inherent in financial statement fraud creates lasting damage to investor confidence, potentially leading to more cautious investment approaches that can stifle market liquidity and innovation. Individual investors who have suffered significant losses often face personal financial hardship, particularly when retirement savings or college funds are affected.

- Institutional investors: This includes pension funds and mutual funds, face additional challenges when falsified financial statements impact their portfolios. These entities have fiduciary responsibilities to their beneficiaries, and significant losses from fraud can affect thousands of retirees and future beneficiaries. The securities litigation process may offer some hope of recovery, and instutution investors produce higher settlement amounts.

Institutional Investors

- Historically strong correlation exists between institutional investor involvement and higher settlement amounts in securities class actions, as institutional investors are more likely to serve as lead plaintiffs in larger cases with greater plaintiff-style damages. However, a recent trend shows declining institutional investor lead plaintiff involvement, which aligns with a decrease in median plaintiff-style damages and overall settlement sizes in 2024.

- Why institutional investors are associated with larger settlements:

- Financial Incentive: Institutional investors have the largest financial interest in the relief sought, a key factor in being named the “most adequate plaintiff” under the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA).

- Larger Cases: Institutional investors are more likely to serve as lead plaintiffs in cases with larger “simplified tiered damages,” which tend to result in bigger settlements.

- Expertise and Oversight: Their involvement suggests a greater capacity for monitoring defendant firms and selecting skilled counsel to achieve better litigation outcomes.

Recent Trends and Declining Settlement Amounts:

- Decreased Institutional Involvement:

In 2024, institutional investors were lead plaintiffs in only 39% of settlements, a 10-year low, according to reports by Cornerstone Research.

- Smaller Settlement Sizes:

This lower level of institutional involvement correlates with lower median plaintiff-style damages and a decrease in overall settlement amounts in 2024 compared to the previous year.

Key Details

- A study analyzing securities lawsuits from 1996 to 2005 showed that cases with institutional lead plaintiffs resulted in larger monetary settlements compared to those with individual lead plaintiffs.Another factor contributing to smaller settlement sizes is the trend of smaller defendant issuers, with a greater percentage declaring bankruptcy or being delisted in 2024, which limits the pool of potential settlement funds.

- In 2023, all nine “mega” settlements (ranging from $102.5 million to $1 billion) included an institutional investor as the lead plaintiff.

- Smaller Defendant Issuers:

- Beyond financial outcomes, these lawsuits, when led by institutional investors, are also associated with improvements in corporate governance, such as increased board independence.

Regulatory Framework and Enforcement MechanismsThe Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002: Fundamentally transformed the regulatory landscape surrounding financial statement fraud, establishing comprehensive requirements for corporate governance and internal controls. This landmark legislation emerged directly from the corporate scandals of the early 2000s, creating new standards for executive accountability and financial reporting accuracy.Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act: Requires public companies to establish and maintain adequate internal controls over financial reporting. Companies must conduct annual assessments of these controls and obtain independent auditor attestations regarding their effectiveness. These requirements create multiple layers of oversight designed to prevent financial statement fraud before it occurs.

Regulatory Framework and Enforcement MechanismsThe Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002: Fundamentally transformed the regulatory landscape surrounding financial statement fraud, establishing comprehensive requirements for corporate governance and internal controls. This landmark legislation emerged directly from the corporate scandals of the early 2000s, creating new standards for executive accountability and financial reporting accuracy.Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act: Requires public companies to establish and maintain adequate internal controls over financial reporting. Companies must conduct annual assessments of these controls and obtain independent auditor attestations regarding their effectiveness. These requirements create multiple layers of oversight designed to prevent financial statement fraud before it occurs.Institutional investor involvement also correlates with higher estimations of potential investor losses, known as plaintiff-style damages, which tend to lead to larger settlements.SEC enforcement Actions: Have become increasingly sophisticated and aggressive in pursuing financial statement fraud cases. The Securities and Exchange Commission nemploys advanced data analytics to identify unusual patterns in financial reporting, enabling earlier detection of potential fraud. When violations are discovered, the SEC can impose substantial monetary penalties, require corrective disclosures, and pursue individual accountability through officer and director bars.

- The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB): Provides additional oversight through its regulation of public company auditors. The PCAOB establishes auditing standards, conducts inspections of audit firms, and can impose sanctions for deficient audit work. This regulatory framework creates accountability throughout the financial reporting ecosystem.

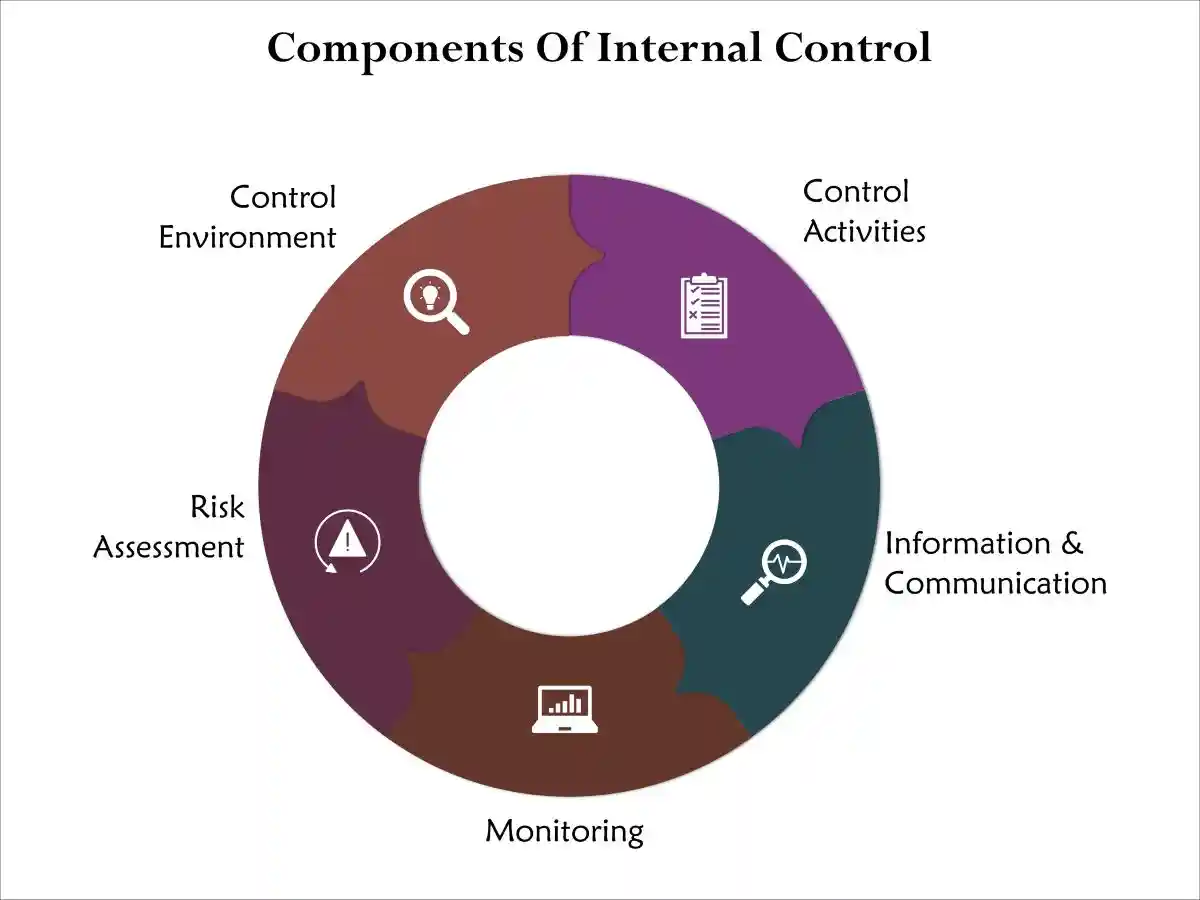

- Disclosure of Internal Contols: Regulatory reporting requirements have expanded significantly since the implementation of Sarbanes-Oxley Act provisions. Companies must provide detailed disclosures about their internal controls, risk factors, and any material weaknesses identified in their control systems. These enhanced disclosure requirements provide investors with more information to assess potential fraud risks.

Case Studies: Learning from Corporate Scandals

Enron

- The Enron scandal remains the quintessential example of how omissions in financial statements can devastate markets and investors.

- The energy company employed sophisticated accounting fraud schemes, including the use of special purpose entities (SPEs) to hide over $1 billion in debt from its balance sheets.

- These corporate scandals involved deliberate omissions of critical financial information that painted a false picture of the company’s financial health.

- Key Legal Precedents Established:

- Enhanced auditor independence requirements under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

- Stricter CEO and CFO certification of financial statements

- Whistleblower protection provisions that encouraged internal reporting of fraud

- The securities litigation that followed resulted in one of the largest bankruptcy proceedings in U.S. history, with investors losing approximately $74 billion in market value.

- The case established crucial precedents for regulatory compliance, particularly regarding the disclosure of off-balance-sheet transactions and the independence of external auditors.

Waste Management

- Waste Management’s senior executives carried out the scheme through a series of fraudulent accounting manipulations.

- The specific mechanisms of the fraud included:

- Manipulated depreciation: Executives repeatedly extended the useful life of company assets, such as garbage trucks, and assigned arbitrary, excessive salvage values to them. This dramatically reduced the annual depreciation expense and artificially boosted profits.

- Improper capitalization of expenses: Maintenance and repair costs for landfills were improperly classified as capital expenses rather than as current-period expenses. This illegally deferred recognition of these costs, making short-term profits appear larger.

- Concealment through “netting”: Management secretly used one-time gains from asset sales to erase unrelated operating expenses and accounting misstatements. This practice, known as “netting,” concealed the true financial health of the company from investors and auditors.

- Inflated environmental reserves: Executives would intentionally inflate environmental liability reserves during strong financial quarters. Then, during weaker quarters, they would release the excess reserves into earnings to boost results.

- Failure to write off impaired assets: The company neglected to write off the costs of abandoned or impaired landfill projects, instead keeping the costs on the balance sheet to hide their negative financial impact.

Tyco International

- The scandal: Former CEO L. Dennis Kozlowski and CFO Mark Swartz embezzled hundreds of millions of dollars from the company in the early 2000s, using it to fund lavish personal lifestyles. To conceal the theft and maintain the appearance of strong financial performance, they made false and misleading statements to investors.

- The litigation: Kozlowski and Swartz were convicted of grand larceny, securities fraud, and other crimes. Tyco settled shareholder lawsuits for $3 billion, one of the largest securities class action settlements at the time, and its auditor paid an additional $225 million to settle claims.

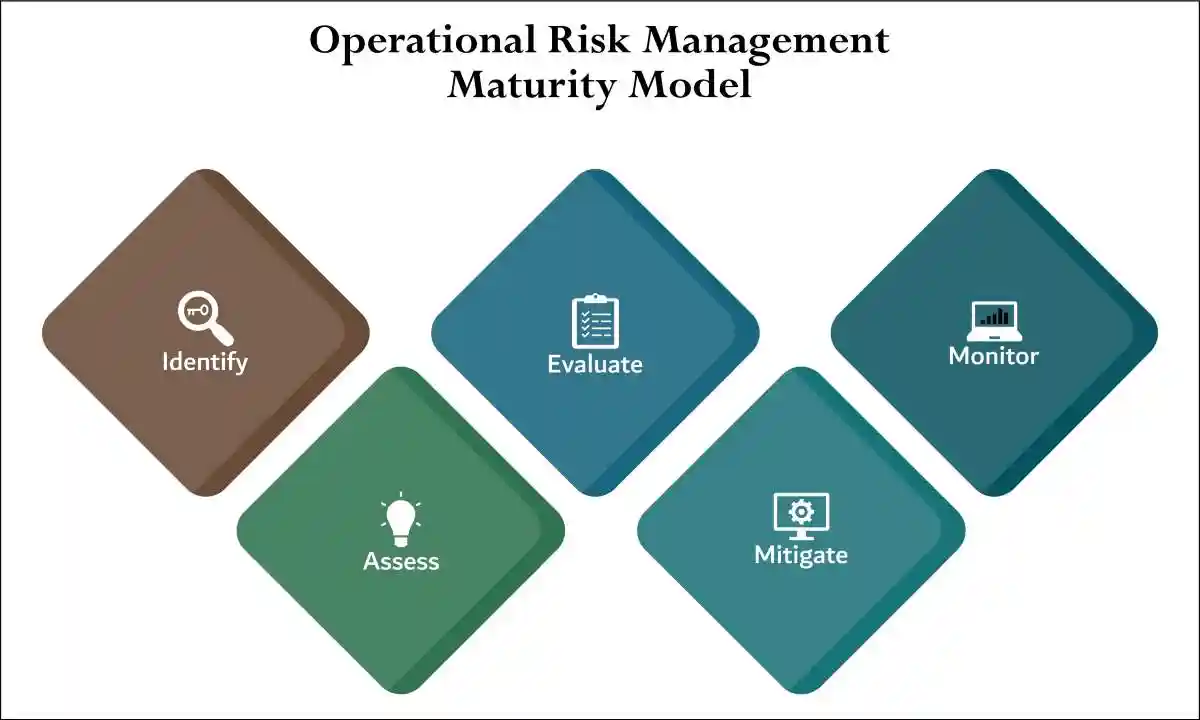

Corporate Governance and Internal Controls

- Effective Corporate Governance: Serves as the primary defense against financial statement fraud, creating accountability structures that discourage fraudulent behavior and promote ethical conduct. Strong governance frameworks establish clear lines of responsibility, ensure appropriate oversight of management activities, and create incentives for accurate financial reporting.

- Internal controls: Represent the operational mechanisms through which corporate governance principles are implemented. These controls include authorization procedures for transactions, segregation of duties to prevent individual control over complete transaction cycles, and regular reconciliation procedures to identify discrepancies. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires companies to maintain these controls and test their effectiveness annually.

- Board Independence: Has emerged as a critical component of effective corporate governance. Independent directors provide objective oversight of management activities and can challenge questionable practices without conflicts of interest. Audit committees composed entirely of independent directors play a particularly important role in overseeing financial reporting processes and relationships with external auditors.

- Risk Assessment: Procedures help companies identify areas where financial statement fraud might occur and implement appropriate preventive measures. These assessments consider factors such as management incentives, industry pressures, and operational complexities that might create opportunities for fraudulent behavior.

Prevention and Detection Strategies

- Proactive Measures: Preventing financial statement fraud requires a comprehensive approach that combines strong internal controls, effective corporate governance, and ongoing monitoring procedures. Companies must create cultures of integrity where ethical behavior is rewarded and fraudulent conduct is quickly identified and addressed.

- Employee training Programs: Play a crucial role in fraud prevention by educating staff about proper procedures, ethical expectations, and reporting mechanisms for suspected misconduct.

- Empasive Fincial Consequences: These programs should emphasize the serious legal and financial consequences of financial statement fraud, including potential securities litigation and regulatory enforcement actions.

- Whistleblower Programs: Provide mechanisms for employees to report suspected fraud without fear of retaliation. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act includes specific protections for whistleblowers who report securities violations, and many companies have established anonymous reporting systems to encourage disclosure of potential problems.

- Technology Advancments: Advanced data analytics and continuous monitoring systems can identify unusual patterns in financial data that might indicate fraudulent activity. These systems can flag transactions that fall outside normal parameters, identify unusual relationships between accounts, and detect patterns consistent with known fraud schemes.

Qualitative Assessment and Management Behavior

- Qualitative Factors: Investors should pay close attention to qualitative factors such as management’s tone and transparency in discussing financial results. Overly optimistic or vague explanations for financial performance can be a warning sign of potential fraud. Management teams that consistently blame external factors for poor performance while taking credit for positive results may be attempting to mask underlying problems.

- Management Trunover: Additionally, high levels of management turnover or frequent changes in auditors may suggest underlying issues within the company. When experienced executives leave suddenly or when companies change audit firms without clear business reasons, investors should investigate further.

- Litigation Landscape: Securities class actions and securities class action lawsuits often emerge when these red flags are ignored and fraud eventually comes to light. The resulting accounting fraud revelations can lead to significant investor losses and lengthy legal proceedings.

- Securities Class Actions: Represent the primary mechanism through which investors seek recovery for losses resulting from financial statement fraud. These lawsuits typically follow a predictable pattern, beginning with the disclosure of accounting irregularities or regulatory enforcement actions that cause significant stock price declines. The resulting investor losses create the foundation for securities class action lawsuits alleging violations of federal securities laws.

- The lead plaintiff selection process: Securities class actions has evolved significantly since the passage of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Institutional investors, particularly pension funds and other large shareholders, often serve as lead plaintiffs due to their substantial losses and resources to oversee the litigation effectively. This institutional involvement has improved the quality of securities class action lawsuits and increased the likelihood of meaningful recoveries for investors.

- Heightened Pleading Standards: Securities class actions must overcome significant procedural hurdles, including heightened pleading standards that require plaintiffs to plead fraud with particularity. The discovery process in these cases often involves extensive document review, expert witness testimony, and complex financial analysis to demonstrate the connection between falsifying financial statements and investor losses. The litigation process typically spans several years and requires substantial financial resources.

PRE- AND POST-PSLRA STANDARDS FOR SECURITIES FRAUD LITIGATION

Feature | Pre-PSLRA Standard | Post-PSLRA Standard |

| Motion to dismiss | Based on “notice pleading” (Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(a)), making it easier for plaintiffs to survive motions to dismiss. This often led to settlements to avoid costly litigation. | Requires satisfying PSLRA’s heightened pleading standards and the “plausibility” standard from Twombly and Iqbal. Failure to plead with particularity on any element can result in dismissal. |

Pleading | “Notice pleading” was generally sufficient, though fraud claims under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b) required particularity for the circumstances of fraud, but intent could be alleged generally. | Each misleading statement must be stated with particularity, explaining why it was misleading. Facts supporting beliefs in claims based on “information and belief” must also be stated with particularity. |

| Scienter | Pleaded broadly; the “motive and opportunity” test was often sufficient to infer intent. | Requires alleging facts creating a “strong inference” of fraudulent intent, which must be at least as compelling as any opposing inference of non-fraudulent intent, as clarified in Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd.. |

Loss causation | Not a significant pleading hurdle, often assumed if a plaintiff bought at an inflated price. | Requires pleading facts showing the fraud caused the economic loss, often by linking a corrective disclosure to a stock price drop. Dura Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Broudo affirmed this. |

Discovery | Could proceed while a motion to dismiss was pending. | Automatically stayed during a motion to dismiss. |

| Safe harbor for forward-looking statements | No statutory protection. | Protects certain forward-looking statements if accompanied by “meaningful cautionary statements”. |

Lead plaintiff selection | Often the first investor to file. | Court selects based on a “rebuttable presumption” that the investor with the largest financial interest is the most adequate. |

| Liability standard | For non-knowing violations, liability was joint and several. | For non-knowing violations, liability is proportionate; joint and several liability applies only if a jury finds knowing violation. |

Mandatory sanctions | Available under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11, but judges were often reluctant to impose them. | Requires judges to review for abusive conduct |

- Dispute Resolving: Settlement negotiations in securities class actions often involve multiple parties, including the company, individual executives, auditors, and insurance carriers. The allocation of settlement funds among these parties reflects their relative culpability for the financial statement fraud and their financial capacity to contribute to investor recovery. Recent settlements have ranged from tens of millions to hundreds of millions of dollars, depending on the scope of the fraud and the resulting investor losses.

THE SECURITIES LITIGATION PROCESS

Filing the Complaint | A lead plaintiff files a lawsuit on behalf of similarly affected shareholders, detailing the allegations against the company. |

| Motion to Dismiss | Defendants typically file a motion to dismiss, arguing that the complaint lacks sufficient claims. |

Discovery | If the motion to dismiss is denied, both parties gather evidence, documents, emails, and witness testimonies. This phase can be extensive. |

Motion for Class Certification | Plaintiffs request that the court to certify the lawsuit as a class action. The court assesses factors like the number of plaintiffs, commonality of claims, typicality of claims, and the adequacy of the proposed class representation. |

Summary Judgment and Trial | Once the class is certified, the parties may file motions for summary judgment. If the case is not settled, it proceeds to trial, which is rare for securities class actions. |

Settlement Negotiations and Approval | Most cases are resolved through settlements, negotiated between the parties, often with the help of a mediator. The court must review and grant preliminary approval to ensure the settlement is fair, adequate, and reasonable. |

Class Notice | If the court grants preliminary approval, notice of the settlement is sent to all class members, often by mail, informing them about the terms and how to file a claim. |

| Final Approval Hearing | The court conducts a final hearing to review any objections and grant final approval of the settlement. |

Claims Administration and Distribution | A court-appointed claims administrator manages the process of sending notices, processing claims from eligible class members, and distributing the settlement funds. The distribution is typically on a pro-rata basis based on recognized losses. |

The Future of Financial Reporting Integrity

- Evolving Trends in Technology: As technology continues to evolve, new tools for preventing and detecting financial statement fraud are emerging. Artificial intelligence and machine learning systems can analyze vast amounts of financial data to identify subtle patterns that might indicate fraudulent activity. Blockchain technology offers potential for creating immutable audit trails that make financial manipulation more difficult.

- Regulatory compliance: The requirements continue to evolve in response to new fraud schemes and technological developments. The SEC regularly updates its guidance and enforcement priorities to address emerging risks and ensure that corporate governance frameworks remain effective.

- ESG Reporting: The integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting with traditional financial reporting creates new opportunities for comprehensive fraud prevention. Companies that maintain strong governance practices across all aspects of their operations are better positioned to prevent financial statement fraud and maintain investor confidence.

- Securities litigation: Continues to serve as an important deterrent to financial statement fraud, providing financial consequences for companies and executives who engage in fraudulent behavior. The threat of substantial legal settlements and personal liability creates powerful incentives for maintaining accurate financial reporting.

- Realizing the Comsquences: Understanding falsifying financial statements and its consequences remains crucial for all market participants. By recognizing the warning signs, implementing effective prevention measures, and maintaining strong corporate governance practices, companies can protect themselves from the devastating consequences of financial statement fraud while investors can make more informed decisions about their investment choices.

Contact Timothy L. Miles Today for a Free Case Evaluation

If you suffered substantial losses and wish to serve as lead plaintiff in a securities class action, or have questions about securities class action settlements, or just general questions about your rights as a shareholder, please contact attorney Timothy L. Miles of the Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles, at no cost, by calling 855/846-6529 or via e-mail at [email protected]. (24/7/365).

Timothy L. Miles, Esq.

Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles

Tapestry at Brentwood Town Center

300 Centerview Dr. #247

Mailbox #1091

Brentwood,TN 37027

Phone: (855) Tim-MLaw (855-846-6529)

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.classactionlawyertn.com

Facebook Linkedin Pinterest youtube

Visit Our Extensive Investor Hub: Learning for Informed Investors