Introduction to Earnings Restatements

Earnings restatements are the revision and republication of a company’s previously issued financial statements to correct a material error, often resulting from mistakes, fraud, or misapplications of accounting standards and lead to secuirites litigaton over internal controls and corporate governance.

Research by Graham et al. (2005) reveals widespread financial misreporting across U.S. markets. Companies and their leaders face serious repercussions from earnings restatements. Corporate restatements have declined since 2006, yet the percentage of stealth restatements has grown substantially in recent years.

Securities litigation and securities class action lawsuits often follow these accounting corrections. Public companies face considerable risk as a result. Court dismissal rates directly impact restatement behavior – companies are 16.6 percentage points more likely to issue voluntary restatements when dismissal rates increase by one standard deviation, compared to the typical rate of 26.50%. CFO turnover rates rise and bonus compensation drops after earnings restatements. These penalties typically apply only when class-action securities litigation emerges from the restatement.

This piece will get into patterns that trigger securities class actions from earnings restatements. We will explore legal implications across different restatement categories and analyze how court jurisdictions shape litigation outcomes. Our insights will clarify the complex interplay between corporate governance, internal controls, and securities litigation risk.

Common Reasons for Restatements

In the decade from 2013 to 2022, the Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals and Computer & Software industries each accounted for 14% of financial statement restatements, ranking just behind the Financial, Banks & Insurance sector. Restatements in these sectors are frequently attributed to complex accounting issues, such as revenue recognition and estimates.

- Complex accounting rules: Both industries deal with highly complex financial reporting, leading to misapplication of accounting standards.

- Healthcare and Pharmaceuticals: Issues can arise with recognizing revenue for research grants or complex drug pricing agreements, or accounting for mergers and acquisitions. The Center for Audit Quality (CAQ) notes that the healthcare industry’s contribution to restatements saw a significant upward trend from 2013 to 2021.

- Computer and Software: Restatements are often triggered by complex revenue recognition rules for bundled software products and services. Other issues include errors in accounting for debt and equity securities.

- Inadequate internal controls: Companies that issue restatements are more likely to have weak internal control over financial reporting and weak corporate governance. An analysis found that companies involved in restatements often had ineffective control snd corporate governance, even if management or auditors only identified these weaknesses after the restatement occurred.

- Errors in estimates and accruals: The most frequent accounting issue cited in restatement announcements is the inappropriate accounting for accruals, reserves, and estimates. This is particularly common in industries that rely on complex long-term contracts and valuation models.

How restatements affect companies

- Lost profitability: Companies that issued restatements were found to be less likely to be profitable for the three years following the announcement.

- Delisting: The CAQ found that 30% of companies issuing restatements were delisted during the study period.

- Increased scrutiny: Restatements can trigger closer scrutiny from regulators like the SEC and create a negative stigma among investors.

- CEO/CFO accountability: The Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires CEOs and CFOs to return certain compensation if a restatement is caused by material noncompliance due to misconduct.

Earnings Restatements as a Trigger for Securities Class Actions

Companies that issue earnings restatements often face a flood of legal consequences. These restatements act as triggers for securities class action lawsuits and create big risks for companies and their executives. This connection comes from the basic principles of securities law that protect investors.

Link between restatements and Rule 10b-5 violations

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) created Rule 10b-5 under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act. This rule serves as the main framework that prohibits securities fraud. The rule makes it illegal to “employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud,” “make any untrue statement of a material fact,” or “involve in any act, practice, or course of business which operates as a fraud or deceit” in securities transactions.

Plaintiffs must prove several key elements to establish a securities fraud claim under Rule 10b-5:

- A material misrepresentation or omission

- Scienter (intent to deceive)

- A connection with securities purchases or sales

- Investor reliance on the misrepresentation

- Economic loss

- Loss causation (the misrepresentation caused the loss)

Cases that deal with financial restatements rarely dispute the “false or misleading statement” element because restatements admit to previous reporting errors. This explains the lower dismissal rates in restatement-related securities class actions. Research shows that accounting cases with financial statement restatements face dismissal less often compared to other securities litigation.

Material misstatements and investor reliance

Materiality plays a vital role in securities litigation. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) calls a restatement “a revision of a previously issued financial statement to correct an error.” Yet it offers little guidance about what makes an inaccuracy “material”. The real test lies in whether the information would affect a reasonable investor’s decisions.

The “fraud on the market” theory from Basic v. Levinson clarified investor reliance in securities fraud claims. This principle assumes that market prices reflect all public material information in an efficient market. Courts can then presume investors relied on the market price’s integrity. A company that issues a restatement admits its previous financial information had material errors that affected market prices.

SEC’s amicus briefs argue that restated financial statements strongly indicate original statements contained material misrepresentations. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) state that restated financial statements “must constitute an admission of past errors”.

Restatements as admissions of prior misreporting

Courts now view restatements as strong evidence in securities litigation. The SEC uses restated financial statements to show false and material information in original statements and prove scienter. Large corrections can suggest knowledge of wrongdoing, which matters for the scienter inquiry.

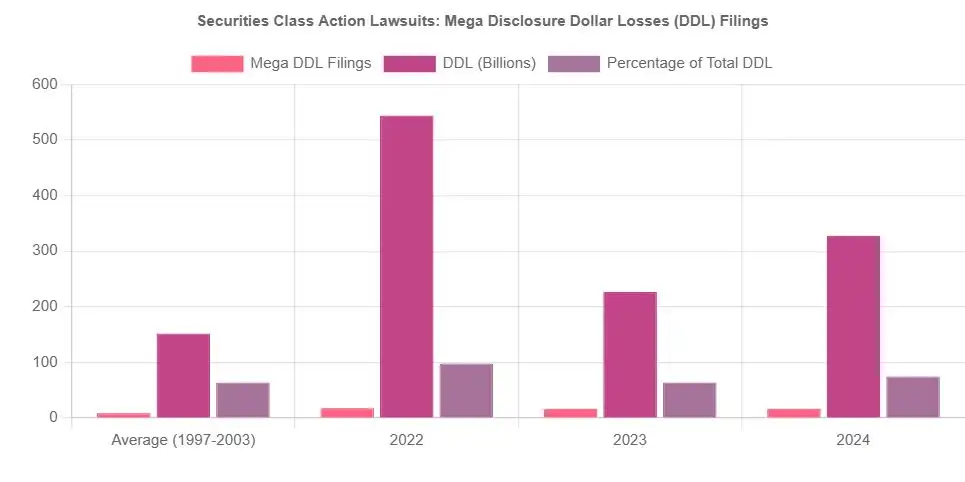

Not every restatement leads to litigation. Accounting case filings with financial statement restatements dropped 55% in 2021, which is 72% below the 2012-2020 average. Yet these cases often result in big settlements. The median settlement matches non-restatement cases at $10.50 million, but “mega-settlements” over $100 million usually involve restatements.

Recent cases show serious consequences for financial misreporting. The SEC fined Hertz Global Holdings $16 million in January 2019 for “materially misstating” pretax income due to accounting errors. Kraft Heinz also had to restate three years of financial reports after an investigation found procurement procedure problems.

Corporate executives should note two things: the SEC takes strong action against inaccurate financial statements, and finding accounting errors often leads to deeper regulatory scrutiny.

District Court Dismissal Rates and Securities Litigation Risk

Securities class action dismissal rates show significant patterns about court behavior and litigation risk. These dismissal patterns substantially affect corporate decisions about earnings restatements and change the litigation landscape for publicly traded companies.

Using dismissal rate as a proxy for court leniency

Federal district courts serve as main gatekeepers for securities lawsuits. Most cases get dismissed or settled under their supervision. Researchers have created new district court-level measures based on past dismissal rates of private securities litigation (PSL) to understand litigation environments. Higher dismissal rates point to greater court leniency and lower litigation risk for firms.

This court-level litigation risk measurement provides great advantages. The measurement substantially affects securities litigation likelihood and outcomes within each jurisdiction. The measurement is exogenously determined and unlikely affected by individual firm characteristics. This reduces endogeneity concerns when we look at connections between litigation risk and disclosure decisions.

The data shows clear connections – misreporting firms based in districts with high-dismissal-rate (lenient) courts tend to make voluntary restatements. A one standard deviation increase in court dismissal rate results in a 16.6 percentage point increase in voluntary restatement propensity compared to an average restatement rate of 26.50%.

Impact of court jurisdiction on securities class action outcomes

Dismissal rates differ dramatically across jurisdictions. This creates substantial differences in litigation risk based on geographic location alone. Courts dismissed securities cases in whole or part about 80% of the time they ruled on motions to dismiss between 2013 and 2022. They denied motions to dismiss entirely only 20% during this period.

The numbers tell an interesting story from 1997 through 2018. Courts dismissed 43% of core federal class action filings, 49% settled, 7% remained active, and less than 1% reached a trial verdict. Recent cases show even higher dismissal rates – 2013 federal securities class actions had a 57% dismissal rate.

Court jurisdiction affects outcomes beyond federal courts substantially. State court dismissal rates (28%) remain lower than federal court rates (39%). California cases drive this trend. California state courts granted motions to dismiss in only 18% of cases filed solely in state court since 2011. Different pleading standards explain this gap – states sometimes use more lenient standards than federal courts.

These findings matter greatly. Strict court decisions make corporations less likely to admit misreporting. Higher litigation risk reduces managers’ willingness to restate previous reporting. Companies strategically evaluate court jurisdiction before deciding to issue restatements.

Tellabs v. Makor as a natural experiment

The Supreme Court case Tellabs v. Makor offers a unique natural experiment. This case helped us understand how court standards affect restatement behavior. The Supreme Court first tried to clarify the “strong inference” standard of scienter (intent to deceive). This standard serves as a core legal component and creates major differences in pleading requirements across federal courts.

Tellabs created a thorough framework to evaluate scienter allegations:

- Courts must accept all factual allegations as true

- Courts must consider allegations collectively, not in isolation

- Courts must think about plausible opposing inferences

- The inference must be “cogent and at least as compelling as any plausible opposing inference“

After Tellabs, previously lenient courts reduced their dismissal rates compared to control courts. Misreporting firms in districts with previously lenient courts decreased their voluntary restatement propensity. Research confirms that Tellabs related to substantially lower dismissal rates on scienter grounds in circuits that previously applied a higher preponderance standard.

This case demonstrates how judicial standards directly shape corporate disclosure behavior. Court standards for pleading securities fraud become more uniform, and corporate restatement behavior follows suit. This highlights the complex relationship between judicial decision-making and financial reporting practices.

Voluntary vs. Involuntary Restatements: Legal Implications

Accounting restatements emerge from a two-stage process starting with financial reporting misstatements and end with their detection and correction. Companies must carefully consider their decision to restate financial statements since it substantially impacts their legal position and shapes how they disclose information.

Timing of restatements and securities litigation exposure

A company’s securities litigation exposure depends heavily on when they announce earnings restatements. Companies that choose to disclose misstatements face a challenging situation: transparency can boost management’s credibility but also creates immediate legal risks. Companies based in districts with high-dismissal-rate (lenient) courts tend to issue voluntary restatements more frequently. These companies believe lenient courts might treat voluntary restatements as evidence that clears them of wrongdoing, possibly dismissing securities class actions due to lack of intent or damages.

This calculated approach explains why many public companies hesitate to admit misreporting. Some companies restate voluntarily, others wait until external parties like the SEC expose the issues, and many never acknowledge their accounting mistakes. Companies essentially bet that future events might help them avoid addressing the misstatement completely.

Stealth restatements and SEC scrutiny

“Stealth restatements” have become increasingly common as companies adjust previous financial statements without explicitly announcing these changes through Form 8-K filings. SEC rules require companies to file within four business days if they determine past financial statements are “no longer reliable” via Item 4.02 of Form 8-K. Many companies choose less transparent methods instead.

Stealth restatements surpassed 50% of all restatements by 2008. Recent data shows this trend growing stronger – stealth disclosures now account for over three-quarters of all restatements during a two-year period. Research reveals a concerning pattern: companies with executives receiving higher equity-based compensation are less likely to issue transparent restatement disclosures.

Not every stealth restatement indicates wrongdoing – minor adjustments legitimately don’t need Item 4.02 disclosure. The SEC watches this practice closely and often asks companies through comment letters why they didn’t file Form 8-K for restatements.

Revision restatements vs. reissuance restatements

Financial reporting has two main restatement categories:

- Reissuance (“Big R”) restatements: Material errors in prior financial statements require these. Companies must file Form 8-K within four business days and restate previous statements through amendments. Markets react strongly to these announcements, which also increase litigation risk.

- Revision (“little r”) restatements: These work best for errors that are not individually material but add up significantly. Companies fix these errors in current comparative statements without refiling previous documents.

Total restatements decreased yearly from 2013 to 2020, but “little r” restatements grew to nearly 76% in 2020 from about 35% in 2005. The SEC noticed that materiality analyzes seem skewed toward concluding errors are not material to previous statements.

Markets respond differently to each restatement type. Revision restatements cause milder market reactions than reissuance restatements, with stock prices dropping 3% less on average. Companies naturally prefer revision restatements, though both types increase audit fees and litigation risk.

Patterns in Restatement Disclosures Across Industries

Looking at financial restatement patterns shows clear industry trends that affect securities litigation risk. Companies in different sectors show varying rates of restatements, and some industries face more accounting errors and legal risks than others.

High-risk sectors: tech, finance, and healthcare

- Financial, Banks & Insurance (17%)

- Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals (14%)

- Computer & Software (14%)

- Increased from 11% in 2013-2014 to 20% in 2021.

- Moved from sixth to second place compared to the previous decade.

- Companies that restate financials are typically smaller.

- Average assets for companies with restatements: $13 billion.

- Average assets for typical companies: $18 billion.

- Companies with serious “4.02 restatements” are even smaller, with average assets of just $2.3 billion.

- Companies with more debt and higher borrowing costs restate more frequently.

- Cash-strapped companies may use aggressive accounting to enhance financial statements.

- This is often done to avoid defaulting on debt agreements or to secure better financing deals.

NYSE vs. OTC companies: restatement frequency

While restatements have dropped since 2006, two patterns stand out. Companies on the New York Stock Exchange and over-the-counter markets show higher restatement rates. NYSE restatements jumped from 65 in 2009 to 108 in 2011.

The total number of restatements fell from 858 in 2013 to 402 in 2022. However, “stealth restatements” – the less transparent kind – have grown. These revision restatements went from 41.5% in 2007 to 64.5% in 2012.

GAAP violations and sector-specific trends

Expense-related problems cause most restatements across industries, making up 35% of all announcements. Many of these came from lease accounting issues that surfaced in early 2005. Revenue recognition issues used to top the list at 38% but are less common now.

Each sector shows its own restatement patterns. Foreign companies in Energy, Mining & Chemical industries restate more often, mainly because mining companies have high restatement rates. The severity of restatements stays similar across industries, with expense-related issues leading in every sector.

New public companies face special challenges. More than three-quarters of companies that went public in 2020-2021 had to restate their financials. These companies struggle with five complex accounting areas: revenue recognition, deferred taxes, leases, equity awards, and earnings per share calculations.

These industry patterns show how each sector’s unique challenges, money pressures, and control issues create securities litigation risks.

Scienter and Materiality in Restatement-Driven Lawsuits

Securities class action lawsuits involving securities fraud restatements depend on two key elements: scienter (fraudulent intent) and materiality (significance to investors). Legal frameworks help courts determine if corporate executives meant to mislead investors or just made mistakes.

Magnitude of restatement and inference of scienter

Financial restatement size and scope often point to potential fraud. Courts disagree about the importance of restatement magnitude. The Third Circuit points out that restatement size strengthens scienter inference, but needs “particularized allegations of fraudulent intent” to prove fraud. Courts that find scienter based on magnitude usually deal with restatements that are “by a lot more drastic” than typical corrections.

This high bar exists because scienter must show behavior far beyond “an extreme departure from the standards of ordinary care”. Courts have ruled that GAAP violations or income restatements alone do not prove securities fraud without proof of intentional deception.

Role of internal controls in establishing intent

Securities fraud cases often feature weak internal controls and lack of corporate governance as evidence of scienter. Poor controls create environments where misstatements go unnoticed. They might also suggest executives tried to avoid safeguards that could catch accounting tricks.

Recent SEC enforcement actions highlight this link by targeting companies with “pervasive, systemic deficiencies” in controls. Investigators discovered “supply chain, finance, and accounting” issues that led to major financial misreporting in one case. A finance director at another company manipulated records, which caused operating income overstatement by 24% and operating loss understatement by 36%.

Market consequences hit companies harder than SEC fines for control problems. These firms often see “precipitous declines in stock prices,” face exchange delistings due to delayed SEC filings, and deal with costly restatements.

Case law: Diamond Foods, Fushi Copperweld

Two key cases show how courts assess scienter and materiality. The court in In re Diamond Foods found enough evidence of scienter based on the “magnitude of wrongful accounting”. Diamond boosted its stock price by recording costs in wrong periods—a “simple and fundamental” GAAP violation. Diamond’s stock fell 36.9% after restating earnings.

North Port Firefighters’ v. Fushi Copperweld showed that small percentage changes can matter when looked at by period instead of overall. Fushi claimed a 4% total earnings adjustment wasn’t material, but the court noted period-specific changes ranged from 8% to 24%. The court found scienter because Fushi misrepresented a “plain vanilla” accounting transaction that executives should have known better.

These cases show courts look at both numbers like restatement size and factors like accounting complexity and disclosure clarity when judging scienter and materiality.

Regulatory Trends and Enforcement Tools

The Securities and Exchange Commission has transformed its methods to detect accounting fraud. Advanced technology and specialized enforcement teams lead this 10-year old approach. The SEC now identifies fraud proactively before investors face substantial losses.

SEC’s RoboCop and data mining for fraud detection

The SEC launched its “RoboCop” system in 2013. This system, officially known as the Accounting Quality Model (AQM), automatically flags suspicious accounting practices. The computerized tool examines financial data in corporate filings to spot companies that stand out in areas like accruals, which management can manipulate. RoboCop analyzes unusual accounting treatments through mandatory XBRL (Extensible Business Reporting Language) tags attached to financial data. Companies face investigation when they change auditors frequently, delay earnings announcements, or show high levels of off-balance-sheet transactions.

Financial Reporting and Audit Task Force priorities

The SEC created the Financial Reporting and Audit Task Force in 2013 alongside RoboCop. This core team of 12 members combines lawyers and accountants with 125 years of enforcement experience. They detect financial reporting fraud earlier than ever before. The Task Force started as a one-year program that could be renewed. They blend traditional investigation methods with innovative data analysis to spot troubling patterns. The team closely watches revenue recognition problems, off-balance-sheet transactions, and companies that revise financial statements multiple times.

Future of securities litigation in accounting fraud

Securities litigation has changed as financial restatements dropped by more than 50% in ten years—from 858 in 2013 to 402 in 2022. The SEC’s enforcement efforts have grown stronger despite this decline. They target both new and repeat offenders with penalties from thousands to millions of dollars. AI will play a bigger role in fraud detection and securities litigation. These systems can process massive amounts of data faster than human experts. They can spot new fraud schemes by learning from past cases without following preset rules.

Conclusion

Earnings restatements without doubt act as powerful triggers for securities litigation and create substantial risks for companies in any sector. This piece explores how accounting corrections often lead to securities class action lawsuits. These cases have lower dismissal rates than other securities litigation. Financial misstatements naturally acknowledge previous errors in reporting, which satisfies a vital element of Rule 10b-5 claims.

The location of courts in securities litigation substantially affects restatement behavior and litigation outcomes. Companies with headquarters in districts known for lenient courts tend to be willing to issue voluntary restatements. Corporate leaders show this strategic behavior after they think over the balance between transparency and potential legal risks.

“Stealth restatements” have become a worrying trend that makes up over three-quarters of all restatements in recent years. This practice might be valid for minor errors, but it has drawn the SEC’s attention lately. Companies need to balance short-term protection against long-term regulatory risks when choosing between revision (“little r”) and reissuance (“Big R”) restatements.

Tech, finance, and healthcare sectors show distinct patterns of vulnerability. Small companies and businesses under financial stress face higher restatement risks because they often adopt aggressive accounting practices under economic pressure.

The size and type of restatements play key roles in determining scienter (fraudulent intent). Courts in securities class action lawsuits do not agree on how much importance to give to restatement size alone. Yet major corrections paired with weak internal controls often build stronger cases for intentional misconduct.

The SEC keeps enhancing its enforcement capabilities through state-of-the-art data mining tools like “RoboCop” and specialized investigative teams. These tools help detect accounting fraud early and potentially prevent major investor losses.

Companies can reduce litigation exposure by improving internal controls, ensuring thorough audits, and evaluating disclosure options based on local legal standards. Investors should learn these patterns to better evaluate risk in their portfolios.

The drop in overall restatement numbers might show better financial reporting quality. But the rise in stealth restatements suggests some companies still prefer to minimize litigation risk rather than be fully transparent. This balance between disclosure requirements and litigation avoidance will definitely shape corporate behavior in coming years.

Key Takeaways

Understanding the hidden patterns in earnings restatements can help companies and investors navigate securities litigation risks more effectively. Here are the essential insights from analyzing restatement-driven lawsuits:

• Restatements trigger litigation with 80% lower dismissal rates – Earnings restatements inherently acknowledge prior reporting errors, making Rule 10b-5 securities fraud claims much easier to prove in court.

• Court jurisdiction dramatically affects restatement strategy – Companies in lenient court districts are 16.6% more likely to voluntarily restate earnings, as they anticipate more favorable legal treatment.

• “Stealth restatements” now dominate at 76% of all corrections – Companies increasingly use less transparent revision methods to avoid triggering Form 8-K disclosure requirements and reduce litigation exposure.

• Tech, finance, and healthcare sectors face highest restatement risks – These industries account for 45% of all restatements, with smaller, financially distressed companies showing the greatest vulnerability.

• SEC’s “RoboCop” system proactively detects accounting fraud – Advanced data mining tools now identify suspicious patterns before substantial investor harm occurs, fundamentally changing enforcement dynamics.

The regulatory landscape continues evolving toward earlier fraud detection and stricter enforcement, making robust internal controls and transparent disclosure practices more critical than ever for public companies seeking to minimize securities litigation exposure.

FAQs

Q1. What triggers securities class action lawsuits related to earnings restatements? Earnings restatements often trigger securities class actions because they acknowledge prior reporting errors, satisfying a key element of fraud claims. Restatements are seen as admissions of material misstatements, which can influence investor decisions and stock prices.

Q2. How does court jurisdiction in securities litigation affect a company’s decision to restate earnings? Companies in districts with lenient courts (higher dismissal rates) are more likely to issue voluntary restatements. They anticipate these courts may treat voluntary disclosures favorably, potentially dismissing lawsuits on grounds of non-scienter or non-damages.

Q3. What are “stealth restatements” and why are they concerning? Stealth restatements are corrections to previous financial statements made without explicitly highlighting changes through Form 8-K filings. They’re concerning because they’ve grown to over 75% of all restatements, potentially reducing transparency and attracting SEC scrutiny.

Q4. Which industries are most vulnerable to earnings restatements and securities class actions? Technology, finance, and healthcare sectors face the highest restatement risks, accounting for about 45% of all restatements. Smaller companies and those under financial pressure are particularly vulnerable due to aggressive accounting practices.

Q5. How is the SEC improving its ability to detect accounting fraud? The SEC has deployed advanced tools like the “RoboCop” system (Accounting Quality Model) that uses data mining to identify suspicious accounting practices. They have also established specialized teams like the Financial Reporting and Audit Task Force to detect fraud earlier.

Contact Timothy L. Miles Today for a Free Case Evaluation

If you suffered substantial losses and wish to serve as lead plaintiff in a securities class action, or have questions about earnings restatements, or just general questions about your rights as a shareholder, please contact attorney Timothy L. Miles of the Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles, at no cost, by calling 855/846-6529 or via e-mail at [email protected]. (24/7/365).

Timothy L. Miles, Esq.

Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles

Tapestry at Brentwood Town Center

300 Centerview Dr. #247

Mailbox #1091

Brentwood,TN 37027

Phone: (855) Tim-MLaw (855-846-6529)

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.classactionlawyertn.com

Visit Our Extensive Investor Hub: Learning for Informed Investors