Introduction to the Three Main Types of Fraud

- The Three Main Types of Fraud: Three main types of fraud are asset misappropriation, financial statement fraud, and corruption.

- Defined: Asset misappropriation involves stealing or misusing company assets, financial statement fraud manipulates financial reports to deceive stakeholders, and corruption includes unethical practices like bribery for personal gain.

- Framework of Fraud: These categories provide a framework for understanding fraud, particularly in a corporate or professional context.

- Asset Misappropriation: Employees or insiders steal or misuse company assets, such as cash, inventory, or equipment.

- Examples: Skimming (taking cash before it’s recorded), payroll fraud, and expense reimbursement fraud.

- Financial Statement Fraud: The deliberate manipulation of a company’s financial statements to deceive investors, creditors, or other stakeholders.

- Examples: Inflating revenues, concealing debts, or falsifying asset valuations to present a false financial picture.

- Corruption: Fraudsters use their influence or position to gain an unfair advantage, often involving bribery and kickbacks.

- Examples: Bribing officials to win contracts, kickback schemes where a vendor gives a portion of a payment to an employee, or conflicts of interest.

- Other common types of fraud include:

- Identity Theft:Using someone else’s personal information for financial gain.

- Investment Fraud:Deceptive practices to lure individuals into fake investments, such as Ponzi schemes.

- Online and Digital Scams:Phishing (using fake emails to get information) and online shopping scams.

- Imposter Scams:Scammers pretend to be a trusted person or organization to trick victims.

Understanding Fraud: Definition and Overview

- Fraud: is a deliberate act of deception aimed at securing an unfair or unlawful gain. It encompasses a wide range of illicit activities that exploit weaknesses in financial systems to benefit the fraudster, often at the expense of individuals, companies, or governments.

- Business Context: In the context of business and finance, fraud can manifest in various forms, such as embezzlement, falsification of records, or bribery.

- Breach of Trust: At its core, fraud is a breach of trust that not only causes direct financial losses but also inflicts long-term damage to the reputation and operational integrity of an organization. As financial systems grow in complexity, so too do the methods and sophistication of fraudulent activities, making them an ever-present threat.

- Impact: The impact of fraud is not confined to financial losses alone. It can erode investor confidence, destabilize markets, and lead to stringent regulatory enforcement measures that affect entire industries.

- Ripple Effect: For businesses, the ripple effects of fraud can result in lost revenue, increased operational costs, and diminished employee morale. In severe cases, it can lead to bankruptcy and legal repercussions for those involved.

- Remedy: Securities class actions have become increasingly common as investors seek recourse for losses resulting from fraudulent activities.

The Mechanics of Fraud, Technology and Taking a Deep Dive

- Nuances and Mechanics: Understanding the nuances and mechanics of fraudulent activities is paramount for mitigating risks and safeguarding assets.

- Technology: Fraud is not a new phenomenon; it has been around for centuries, evolving alongside economic systems. However, the digital age has introduced new challenges, as technology provides both opportunities for fraudsters and tools for detection and prevention.

- Exploring the Three Main Types of Fraud: In this comprehensive guide, we will explore The Three Main Types of Fraud that continue to plague organizations globally: Asset Misappropriation, Financial Statement Fraud, and Corruption. Each type presents unique challenges, but they all share the common trait of exploiting trust for personal or organizational gain.

THE CIRCLE OF RISK MANAGEMENT

The Importance of Fraud Awareness in 2025

- Heightened Fraud Awareness: In 2025, the need for heightened fraud awareness is more critical than ever, given the rapid advancement of technology and the globalization of markets.

- Digital Platforms: As businesses increasingly rely on digital platforms for transactions, the risk of cyber-fraud has surged, making it essential for organizations to implement comprehensive security measures.

- Reshape Business: The digital transformation of industries has not only reshaped how we conduct business but also introduced new vulnerabilities that fraudsters are quick to exploit.

Compliance and Corporate Governance

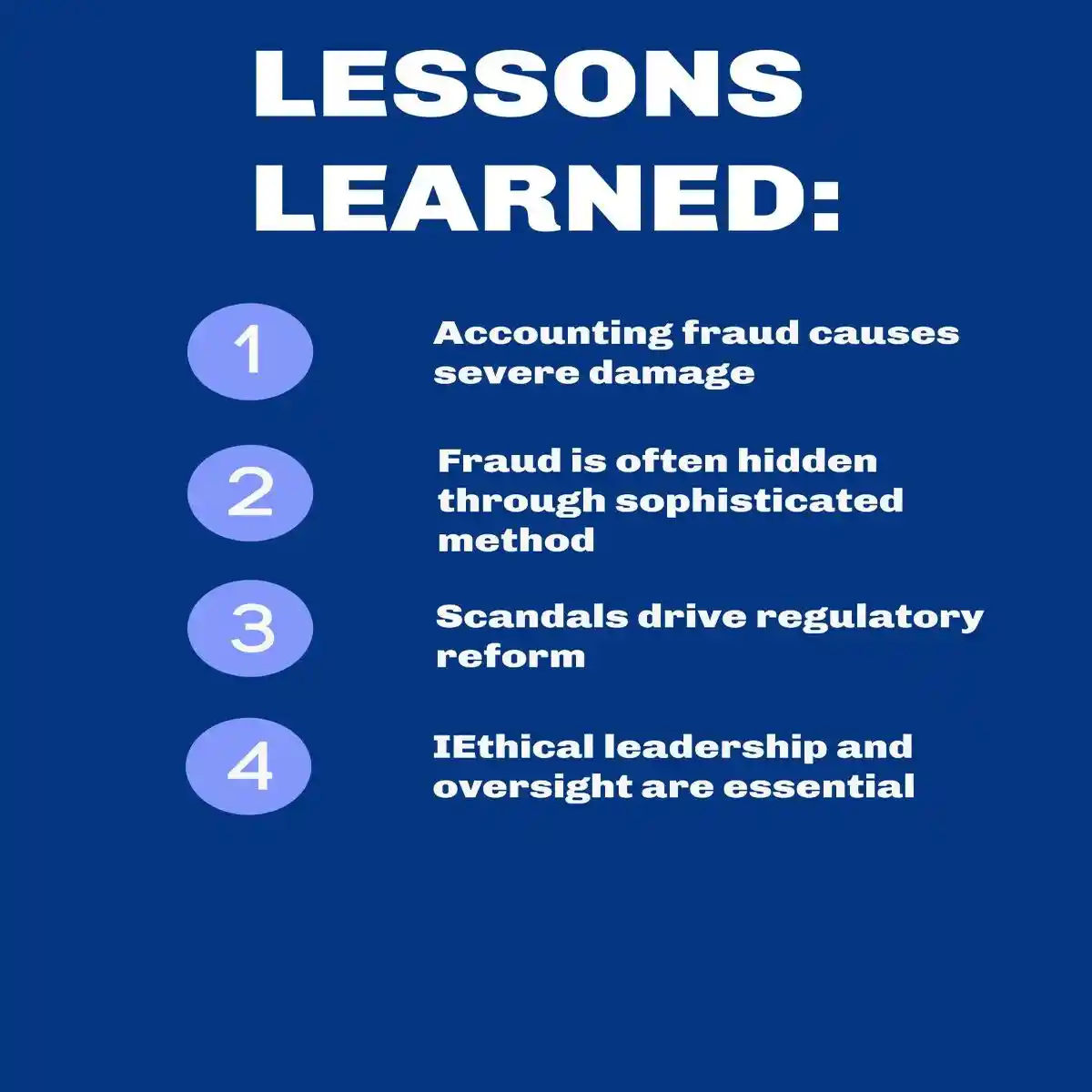

- Regulatory compliance: Has become increasingly stringent following major corporate scandals of the early 2000s. Organizations must now navigate complex webs of regulatory requirements, each with its own implications for internal controls and fraud prevention.

- Non-Compliance: The cost of non-compliance can be devastating, with regulatory fines often exceeding $25 million and securities litigation resulting in settlements ranging from $50 million to $500 million.

- Corporate Governance: The importance of corporate governance cannot be overstated in today’s business environment.

- First Line of Defense: Strong governance frameworks serve as the first line of defense against fraudulent activities, creating multiple layers of protection through effective board oversight, transparent communication, and accountability measures.

Asset Misappropriation: The Most Common Form of Fraud

- Asset Misappropriation: Represents the most frequently occurring type of fraud, accounting for approximately 89% of all fraud cases according to recent industry studies.

- Breach of Trust: This form of fraud involves the theft or misuse of an organization’s assets by employees, management, or third parties who have been entrusted with those assets.

Common Schemes in Asset Misappropriation

- Asset Misappropriation: Can take numerous forms, each designed to exploit different vulnerabilities within an organization’s control systems:

- Cash Schemes: Represent the most direct form of asset misappropriation. These include:

- Skimming: Where cash is stolen before it enters the accounting system.

- Cash Larceny: Where recorded cash is stolen after entry.

- Fraudulent disbursements through billing schemes: Occur when an employee manipulates the invoicing process to cause a company to issue an unauthorized payment.

- Payroll Fraud: Involves manipulating a company’s payroll system to steal money and can be committed by both employees and employers.

- Expense Reimbursement: The process where a business repays an employee for business-related expenses they have paid for personally, such as travel, supplies, or meals.

- Inventory and Equipment Theft: Involves the unauthorized removal of physical assets from company premises. This type of fraud is particularly prevalent in retail and manufacturing environments where large quantities of valuable inventory are maintained.

- Misuse of Company Resources: Includes using company equipment, vehicles, or facilities for personal purposes without authorization. While seemingly minor, these activities can result in significant cumulative losses over time.

Prevention Strategies for Asset Misappropriation

Multi-Layered Approach: Preventing asset misappropriation requires a multi-layered approach that combines robust internal controls with ongoing monitoring and oversight:

- Segregation of Duties: Ensures that no single individual has control over all aspects of a financial transaction. By requiring multiple people to be involved in processes such as purchasing, receiving, and payment authorization, organizations create natural checkpoints that make fraudulent activities more difficult to execute and conceal.

- Regular Audits: Serve as both a deterrent and a detection mechanism. Surprise audits of cash handling procedures, inventory counts, and expense reports can identify discrepancies before they become significant losses.

- Employee Training Programs: Should educate staff about fraud risks, company policies, and the importance of reporting suspicious activities. When employees understand these policies and their role in preventing fraud, they become an integral part of the organization’s internal controls system.

Financial Statement Fraud: The Most Costly Deception

Financial Statement Fraud: Refers to the intentional misstatement or omission of material information in financial reports. While less common than asset misappropriation, occurring in only about 10% of fraud cases, it typically results in the highest financial losses, with median losses exceeding $954,000 per incident.

Understanding Accounting Fraud Mechanisms

- Accounting Fraud Through Financial Statement Manipulation: Takes many sophisticated forms, each designed to present a rosier financial picture than reality warrants:

- Revenue Recognition Fraud: Involves recording revenue that has not been earned or inflating revenue figures through fictitious sales. Companies may engage in channel stuffing, where products are shipped to customers before they are ordered, or create entirely fictitious transactions to boost reported sales figures.

- Expense Manipulation: Includes understating expenses, capitalizing costs that should be expensed, or shifting expenses between periods to smooth earnings. This practice can significantly distort a company’s true financial performance and mislead investors about operational efficiency.

- Asset Valuation Fraud: Involves overstating asset values through improper accounting methods, failing to write down impaired assets, or creating fictitious assets. Inventory manipulation represents one of the most sophisticated yet devastating forms of this fraud type.

Notable Cases of Financial Statement Fraud

Enron

- The Enron scandal remains the quintessential example of howomissions in financial statements can devastate markets and investors.

- The energy company employed sophisticated accounting fraud schemes, including the use of special purpose entities (SPEs) to hide over $1 billion in debt from its balance sheets.

- These corporate scandals involved deliberate omissions of critical financial information that painted a false picture of the company’s financial health.

- Key Legal Precedents Established:

- Enhanced auditor independence requirements under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

- Stricter CEO and CFO certification of financial statements

- Whistleblower protection provisions that encouraged internal reporting of fraud

- The securities litigation that followed resulted in one of the largest bankruptcy proceedings in U.S. history, with investors losing approximately $74 billion in market value.

- The case established crucial precedents for regulatory compliance, particularly regarding the disclosure of off-balance-sheet transactions and the independence of external auditors.

Waste Management

- Waste Management’s senior executives carried out the scheme through a series of fraudulent accounting manipulations.

- The specific mechanisms of the fraud included:

- Manipulated depreciation: Executives repeatedly extended the useful life of company assets, such as garbage trucks, and assigned arbitrary, excessive salvage values to them. This dramatically reduced the annual depreciation expense and artificially boosted profits.

- Improper capitalization of expenses: Maintenance and repair costs for landfills were improperly classified as capital expenses rather than as current-period expenses. This illegally deferred recognition of these costs, making short-term profits appear larger.

- Concealment through “netting”: Management secretly used one-time gains from asset sales to erase unrelated operating expenses and accounting misstatements. This practice, known as “netting,” concealed the true financial health of the company from investors and auditors.

- Inflated environmental reserves: Executives would intentionally inflate environmental liability reserves during strong financial quarters. Then, during weaker quarters, they would release the excess reserves into earnings to boost results.

- Failure to write off impaired assets: The company neglected to write off the costs of abandoned or impaired landfill projects, instead keeping the costs on the balance sheet to hide their negative financial impact.

The role of Arthur Andersen

- Waste Management’s longtime auditor, Arthur Andersen, was complicit in the fraud.

- The audit firm was aware of Waste Management’s improper accounting practices and documented numerous issues, but it repeatedly approved the company’s financial statements with an “unqualified” or “clean” opinion.

- The relationship was tainted by a conflict of interest. Many of Waste Management’s top financial officers were former Arthur Andersen employees, and Andersen was highly protective of the lucrative relationship with its “crown jewel” client.

- Andersen also received substantial fees for non-audit consulting services, which compromised its independence.

Unraveling and consequences

- Discovery: The scheme was discovered in 1997 after a new CEO took over and ordered a review of the company’s accounting practices. He resigned months later after calling the accounting “spooky”.

- Financial restatement: In 1998, Waste Management announced it would restate its earnings from 1992 through 1997, revealing over $1.7 billion in overstated profits.

- Regulatory action: The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) charged Waste Management’s founder and five other top executives with perpetrating the fraud.

- Executives were fired and faced charges of securities fraud. The SEC also fined Arthur Andersen $7 million for its role.

- Stock price collapse: When the fraud was revealed, the company’s stock price plummeted, causing over $6 billion in losses for shareholders.

- Company restructure: Crippled by the scandal, Waste Management was acquired by a smaller competitor, USA Waste Services. The newly merged company kept the Waste Management name but relocated its headquarters and replaced nearly all top executives.

- Legacy for auditors: The scandal was a major contributing factor to the downfall of Arthur Andersen, which was also implicated in the Enron scandal just a few years later.

- Broader reforms: The Waste Management case, alongside other major financial scandals, helped trigger the push for stricter regulations in corporate governance and financial reporting, ultimately leading to the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002.

Tyco International

- The scandal: Former CEO L. Dennis Kozlowski and CFO Mark Swartz embezzled hundreds of millions of dollars from the company in the early 2000s, using it to fund lavish personal lifestyles. To conceal the theft and maintain the appearance of strong financial performance, they made false and misleading statements to investors.

- The litigation: Kozlowski and Swartz were convicted of grand larceny, securities fraud, and other crimes. Tyco settled shareholder lawsuits for $3 billion, one of the largest securities class action settlements at the time, and its auditor paid an additional $225 million to settle claims.

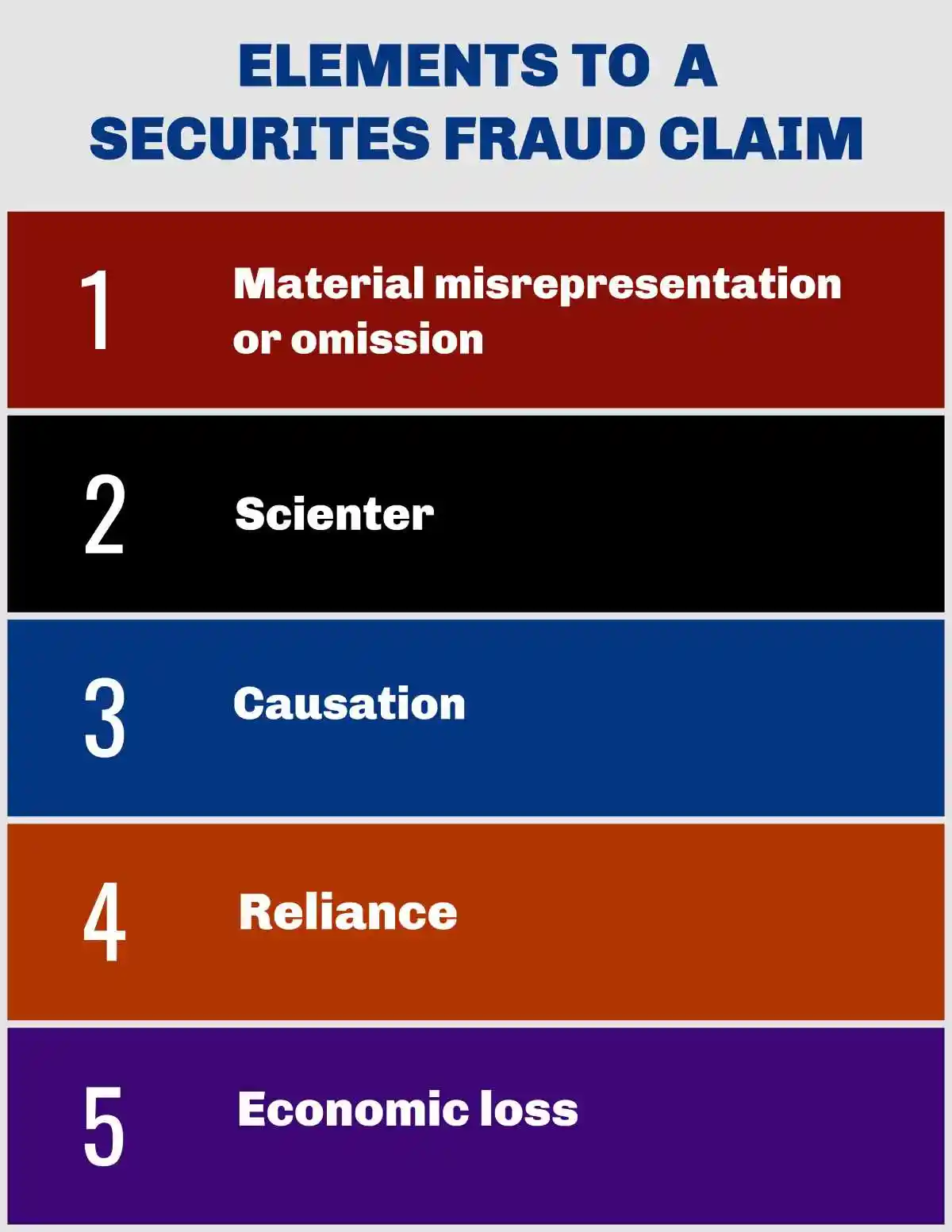

The Role of Securities Class Actions in Financial Statement Fraud

- Securities Class Actions: When accounting fraud occurs, affected investors often seek recourse through securities class actions and securities litigation. These legal mechanisms provide a pathway for investors to recover losses resulting from materially misleading financial statements and other violations of federal securities laws.

- The pressure to “beat-the-street”: Has emerged as one of the most significant catalysts for securities litigationin modern financial markets.

- Resort to Fraud: When companies face declining sales, increased competition, or economic downturns, management may resort to fraudulent practices to avoid reporting losses that could trigger securities litigation or damage their market reputation.

THE SECURITIES LITIGATION PROCESS

| Filing the Complaint | A lead plaintiff files a lawsuit on behalf of similarly affected shareholders, detailing the allegations against the company. |

| Motion to Dismiss | Defendants typically file a motion to dismiss, arguing that the complaint lacks sufficient claims. |

| Discovery | If the motion to dismiss is denied, both parties gather evidence, documents, emails, and witness testimonies. This phase can be extensive. |

| Motion for Class Certification | Plaintiffs request that the court to certify the lawsuit as a class action. The court assesses factors like the number of plaintiffs, commonality of claims, typicality of claims, and the adequacy of the proposed class representation. |

| Summary Judgment and Trial | Once the class is certified, the parties may file motions for summary judgment. If the case is not settled, it proceeds to trial, which is rare for securities class actions. |

| Settlement Negotiations and Approval | Most cases are resolved through settlements, negotiated between the parties, often with the help of a mediator. The court must review and grant preliminary approval to ensure the settlement is fair, adequate, and reasonable. |

| Class Notice | If the court grants preliminary approval, notice of the settlement is sent to all class members, often by mail, informing them about the terms and how to file a claim. |

| Final Approval Hearing | The court conducts a final hearing to review any objections and grant final approval of the settlement. |

| Claims Administration and Distribution | A court-appointed claims administrator manages the process of sending notices, processing claims from eligible class members, and distributing the settlement funds. The distribution is typically on a pro-rata basis based on recognized losses. |

Corruption: The Abuse of Entrusted Power

- Corruption: Involves the abuse of entrusted power for private gain and represents one of the most insidious forms of fraud. While accounting for only about 38% of fraud cases, corruption schemes often involve senior management and can result in significant financial and reputational damage.

Types of Corruption Schemes

- Bribery and Kickbacks: Involve offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting something of value to influence business decisions. These schemes can distort competition, inflate costs, and compromise the integrity of business relationships.

- Conflicts of Interest: Occur when individuals in positions of trust have undisclosed financial interests that could influence their decision-making. This might include awarding contracts to companies in which they have ownership stakes or hiring relatives without proper disclosure.

- Economic Extortion: Involves the wrongful use of actual or threatened force, violence, or fear to obtain money, property, or services. In business contexts, this might manifest as demanding payments in exchange for favorable treatment or threatening adverse consequences for non-compliance.

The Global Impact of Corruption

- Far Reaching Effects: Corruption has far-reaching consequences that extend beyond individual organizations. It can distort market competition, undermine economic development, and erode public trust in institutions.

- Costs Trillions Worldwide: The World Bank estimates that corruption costs the global economy trillions of dollars annually, with developing countries bearing a disproportionate burden.

- Regulatory Enforcement: Agencies worldwide have intensified their efforts to combat corruption, particularly in international business transactions.

- FCPA: The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) in the United States and similar legislation in other countries have created significant legal risks for companies engaged in corrupt practices.

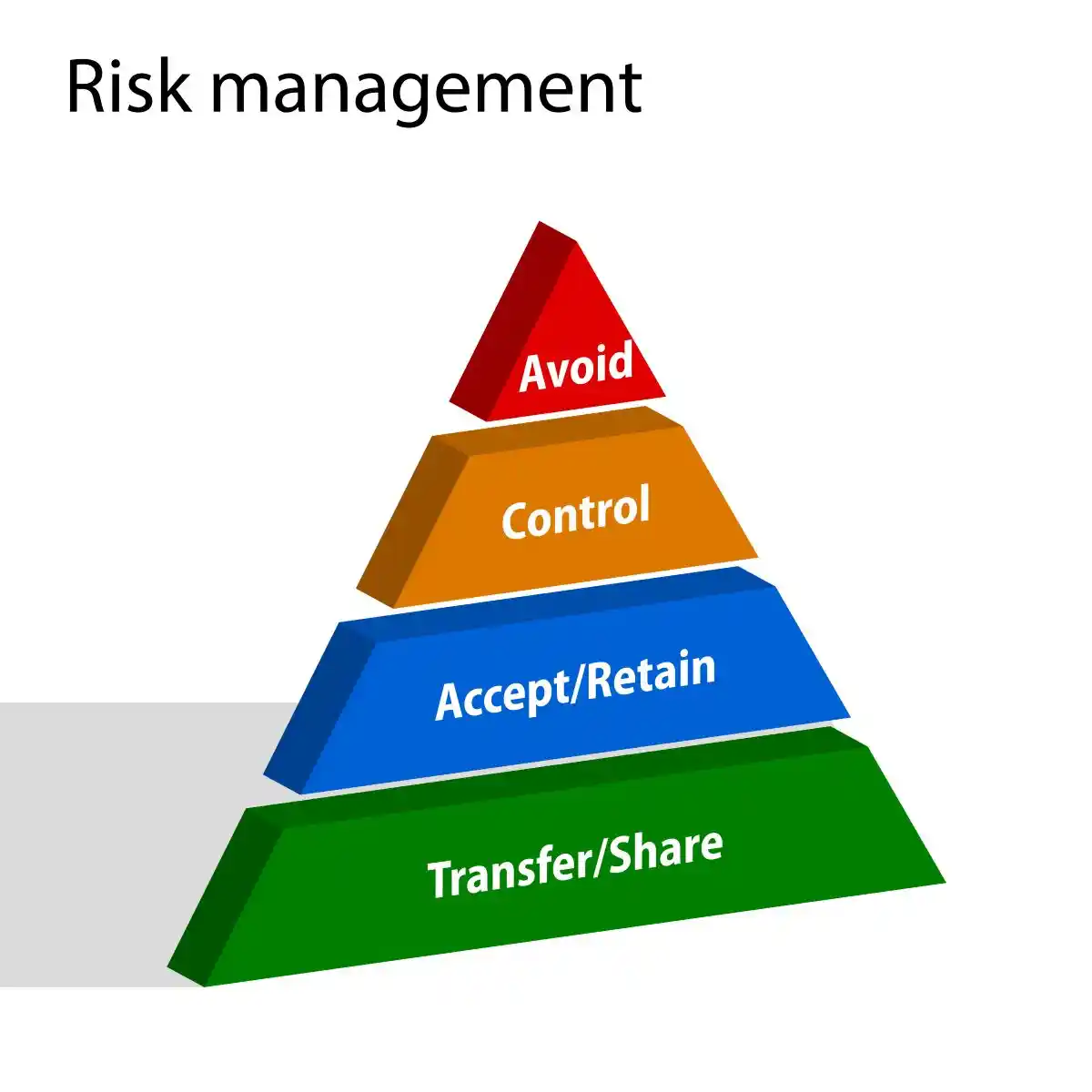

Risk Assessments: The Foundation of Fraud Prevention

- Effective Fraud Prevention: Begins with comprehensive Risk Assessments that identify vulnerabilities and evaluate the likelihood and potential impact of different fraud schemes. These assessments should be conducted regularly and updated as business conditions change.

- Risk Assessment Methodologies: Should consider both internal and external factors that could contribute to fraud risk. Internal factors include organizational culture, management tone, employee morale, and the effectiveness of internal controls. External factors encompass industry conditions, regulatory environment, and competitive pressures.

- Assessment: The assessment process should involve multiple stakeholders, including management, internal audit, legal counsel, and external auditors. This collaborative approach ensures that all perspectives are considered and that risk mitigation strategies address the full spectrum of potential threats.

Building Robust Internal Controls

- Internal controls: Represent the cornerstone of any effective fraud prevention program. These controls should be designed to prevent, detect, and respond to fraudulent activities across all areas of the organization.

- Preventive Controls: Are designed to stop fraud before it occurs. These include authorization requirements, segregation of duties, physical safeguards, and approval processes. The goal is to make fraudulent activities so difficult to execute that potential perpetrators are deterred from attempting them.

- Detective Controls: Are designed to identify fraudulent activities after they have occurred but before significant damage is done. These include reconciliations, analytical reviews, exception reports, and monitoring systems. Early detection is crucial for minimizing losses and preserving evidence for potential legal proceedings.

- Responsive Controls: Ensure that identified fraud incidents are handled appropriately. This includes investigation procedures, corrective actions, and communication protocols. The organization’s response to fraud incidents sends a strong message about its commitment to ethical conduct and can serve as a deterrent to future misconduct.

The Role of Technology in Fraud Prevention and Detection

- Technology: Plays an increasingly important role in both perpetrating and preventing fraud. Advanced analytics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning algorithms can identify patterns and anomalies that might indicate fraudulent activity.

- Data Analytics: Tools can process vast amounts of transaction data to identify unusual patterns, outliers, and red flags that warrant further investigation. These tools can detect subtle indicators of fraud that might be missed by traditional audit procedures.

- Blockchain Technology: Offers promise for preventing certain types of fraud by creating immutable records of transactions. The decentralized and transparent nature of blockchain can make it extremely difficult to manipulate financial records without detection.

- Continuous Monitoring: Systems can provide real-time alerts when suspicious activities occur, enabling organizations to respond quickly to potential fraud incidents. These systems can be particularly effective in detecting asset misappropriation and unusual financial statement entries.

Employee Training and Whistleblower Programs

- Employee Training: On fraud awareness and prevention is essential for creating a culture of integrity within organizations. Training programs should educate employees about different types of fraud, red flags to watch for, and proper reporting procedures.

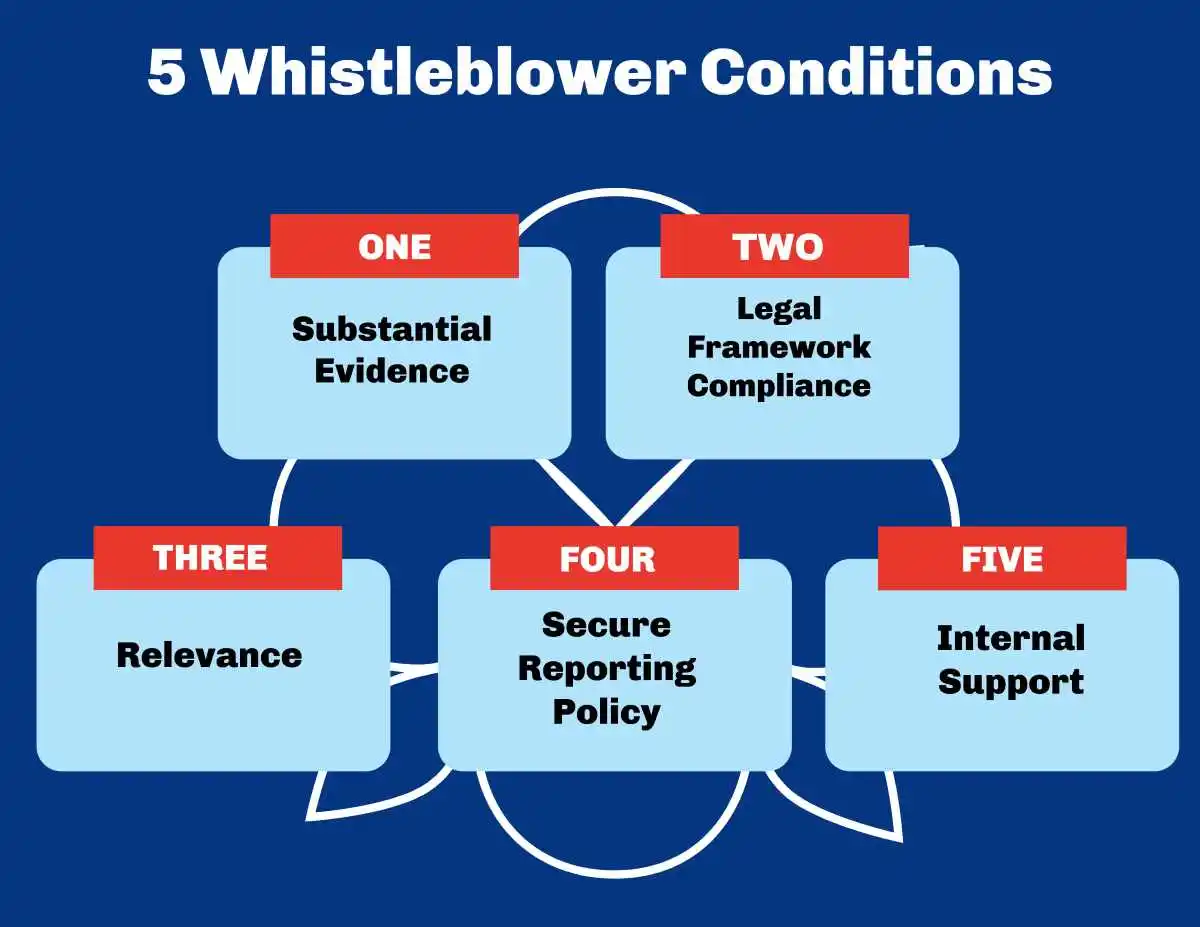

- Whistleblower Programs: Provide employees with safe and confidential channels for reporting suspected fraudulent activities. These programs have proven to be one of the most effective methods for detecting fraud, with tips from employees accounting for approximately 43% of fraud discoveries according to industry studies.

- Strong Protections for Whistleblowers: Effective whistleblower programs must include strong anti-retaliation protections, multiple reporting channels, and clear procedures for investigating reported concerns. Organizations should regularly communicate the availability of these programs and recognize employees who report suspicious activities in good faith.

Regulatory Compliance and Corporate Governance

- Regulatory compliance: Requirements have evolved significantly in response to major corporate scandals. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 fundamentally transformed the landscape of internal control requirements, mandating that public companies establish and maintain adequate internal control over financial reporting.

- Corporate governance: Frameworks must address specific areas of vulnerability that have historically led to corporate scandals. This includes establishing strong tone at the top, ensuring effective board oversight, maintaining transparent communication, and fostering a culture of accountability.

- Ethics Integration: The integration of ethical guidelines with operational controls creates multiple layers of protection against fraud and misconduct. When these principles are woven into the fabric of daily operations, they influence everything from hiring decisions to performance evaluations.

The Future of Fraud Prevention

Future Landscape: As we look to the future, the landscape of fraud prevention is poised for significant transformation. Emerging technologies, evolving regulatory requirements, and changing business models will continue to shape how organizations approach fraud risk management.

Technology Advancements: The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning into fraud detection systems will enable more sophisticated analysis of patterns and behaviors. These technologies can process vast amounts of data in real-time, identifying potential fraud indicators that might be missed by traditional methods.

Regulatory Enforcement: Agencies are also evolving their approaches, utilizing advanced analytics and data mining techniques to identify potential violations. Organizations must stay ahead of these developments by implementing robust compliance programs that can adapt to changing regulatory expectations.

Prevent Cost Analyst: The cost of prevention invariably proves far less than the price of remediation, making proactive compliance not just a legal necessity but a sound business strategy that protects all stakeholders’ interests.

Protection: By implementing comprehensive prevention strategies that combine robust internal controls, regular audits, thorough risk assessments, and strong corporate governance practices, organizations can protect themselves from the devastating consequences of fraud.

Understanding The Three Main Types of Fraud: – Asset Misappropriation, Financial Statement Fraud, and Corruption – is essential for developing effective prevention and detection strategies. Each type presents unique challenges, but they all share the common trait of exploiting trust for personal or organizational gain.

Vigilance: By staying informed about evolving fraud tactics, implementing strong internal controls, and fostering a culture of integrity, organizations can significantly reduce their fraud risk and protect their stakeholders’ interests.

Long-Term Success: The investment in effective controls represents not merely a compliance obligation but a fundamental business imperative that supports long-term success and market confidence. As financial systems continue to evolve and become more complex, the importance of fraud awareness and prevention will only continue to grow.

Contact Timothy L. Miles Today for a Free Case Evaluation

If you suffered substantial losses and wish to serve as lead plaintiff in a securities class action, or have questions about securities class action settlements, or just general questions about your rights as a shareholder, please contact attorney Timothy L. Miles of the Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles, at no cost, by calling 855/846-6529 or via e-mail at [email protected]. (24/7/365).

Timothy L. Miles, Esq.

Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles

Tapestry at Brentwood Town Center

300 Centerview Dr. #247

Mailbox #1091

Brentwood,TN 37027

Phone: (855) Tim-MLaw (855-846-6529)

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.classactionlawyertn.com

Facebook Linkedin Pinterest youtube

Visit Our Extensive Investor Hub: Learning for Informed Investors