Introduction to Securities Class Action Litigation

Securities class action litigation has come a long way since the 1929 Wall Street crash. The last decade shows the massive scale of these cases, with six settlements going beyond $2 billion. These numbers demonstrate how deeply these cases affect our financial markets.

have played a crucial role in protecting investors through the years. The Securities Act of 1933 brought much-needed transparency to the securities market and aimed to rebuild investor trust. Legal scholars have raised concerns that securities fraud class actions might discourage companies from voluntary disclosure.

The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) of 1995 changed the landscape by setting stricter rules for securities class actions. Plaintiffs now faced higher filing thresholds and specific pleading requirements. These changes applied only to federal courts, which led to additional reforms. A newer study, published by researchers shows these reforms’ effects – state courts saw 77 Section 11 cases during 2018-2019, up from just 33 in 2016-2017.

This piece will take you through the complete progress of class action securities litigation. We will start from its early beginnings and move to modern reform efforts, while exploring how these legal tools balance investor protection against frivolous lawsuits.

Investor Protection Before Federal Reform

The US investor protection system has roots that go back well before today’s reforms. The 1929 stock market crash led Congress to create federal securities laws. These laws aimed to rebuild investor confidence through required disclosure and rules against fraud.

Securities Act of 1933: Section 11 Liability

The Securities Act of 1933, known as the “truth in securities” law, created the first detailed federal rules for securities offerings. The legislation had two main goals: companies needed to give investors key financial information about public securities, and deception and fraud in securities deals became prohibited.

Section 11 of the Securities Act became a powerful shield for investors. It let buyers take legal action against various parties involved in registration. Anyone who bought a security could sue if the registration statement had important false statements or left out vital information. Section 11 imposed strict liability, which meant a much lower burden than later rules. Defendants could be liable whatever their intentions were.

The law named specific potential defendants:

- Individuals who signed the registration statement

- Directors or partners of the issuer

- Named prospective directors or partners

- Experts (accountants, engineers, appraisers) who certified parts of the registration statement

- Underwriters involved with the security

Section 11 worked differently from later rules. It applied only to public offerings and plaintiffs had to link their securities directly to the offering with the fraudulent registration statement. This tracing requirement later became a key factor in securities lawsuit strategy.

Securities Exchange Act of 1934: Rule 10b-5 Enforcement

The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 gave the SEC broad control over the securities industry. The SEC gained power to regulate brokerage firms, transfer agents, clearing agencies, and self-regulatory organizations.

Rule 10b-5 became the main tool to fight fraud in securities law. The rule made it illegal for anyone to “employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud,” make false statements about important facts, or run fraudulent business practices in securities deals.

Rule 10b-5 enforcement worked differently from Section 11’s strict liability. It required proof of scienter—showing intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud. Plaintiffs also had to show they relied on the false information and lost money because of it.

Courts later decided Rule 10b-5 allowed private lawsuits, not just SEC enforcement. This interpretation became vital for securities class actions to develop.

Rise of Class Action Securities Litigation in the 1980s-90s

Securities class action lawsuits exploded during the 1980s and early 1990s. Many cases followed stock price drops caused by market factors rather than fraud. Defendants often settled these cases instead of fighting them in court, even when the claims were weak.

The legal world changed as accounting firms and Silicon Valley companies started talking about a “litigation explosion” in securities fraud class actions. Critics pointed out that settlements depended more on defendants’ money than the actual merit of claims.

Congress took notice as these lawsuits kept growing. They found that filing these cases was too easy, which led to more lawsuits. This discovery, plus heavy industry lobbying, led to big changes in the law.

The growth of class action securities lawsuits showed problems with existing laws. Courts tried to balance protecting investors with stopping frivolous cases and their economic effects. These challenges led to major legal changes that would revolutionize securities litigation for years to come.

The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (PSLRA)

Congress passed the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (PSLRA) as a response to the flood of securities lawsuits in the early 1990s. The act aimed to stop what lawmakers saw as “baseless and extortionate securities lawsuits” that hurt “the entire U.S. economy”. This legislation altered the map of securities class action litigation by addressing concerns about nuisance lawsuits that had more settlement value than actual merit.

Heightened Pleading Standards for Securities Fraud Class Actions

The PSLRA created substantially stricter pleading requirements for securities fraud complaints. Plaintiffs now just need to “state with particularity… the facts constituting the alleged violation” and show “acts giving rise to a strong inference that the defendant acted with the required state of mind” (scienter). This new standard goes well beyond the general pleading requirements that Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b) previously used for securities fraud allegations.

The Supreme Court made things clearer in 2007. A “strong inference” of scienter must be “cogent and at least as compelling as any opposing inference one could draw from the facts alleged”. Plaintiffs must now present specific facts that show a defendant’s culpability instead of relying on conclusory allegations. Courts must dismiss complaints that don’t meet these higher standards.

Lead Plaintiff Rule and Institutional Investor Preference

The PSLRA changed how courts select lead plaintiffs in securities class actions. Plaintiffs must spread notice in a “widely circulated national business-oriented publication or wire service” within 20 days after filing a complaint. The court then picks the class member with the biggest financial stake as lead plaintiff, who they believe will best represent class members’ interests.

This rule specifically targets institutional investors—pension funds, mutual funds, and other large investors—to step up as lead plaintiffs. The law assumes these institutions would negotiate better with class counsel, watch the litigation more carefully, and reduce attorney fees. Yes, it is common for courts to choose financial institutions over other investors in lead plaintiff contests.

Discovery Stay During Motion to Dismiss

The PSLRA brought a big change by automatically stopping “all discovery and other proceedings” while a motion to dismiss is pending. This prevents plaintiffs from using expensive discovery costs to force settlements in weak cases. Courts have broadly interpreted this rule, even applying it before defendants formally file a motion to dismiss if they’ve shown intent to file one.

Safe Harbor for Forward-Looking Statements

Securities litigation made corporate management hesitant to share financial projections. The PSLRA created a safe harbor to protect forward-looking statements. Companies get protection when they clearly label these statements and include “meaningful cautionary statements identifying important factors that could cause actual results to differ materially”.

Companies won’t face liability for incorrect predictions if they gave proper warnings. Courts have rejected generic disclaimers and require “detailed and specific” cautionary language. The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals explained this well: a disclaimer wouldn’t protect someone who “warns his hiking companion to walk slowly because there might be a ditch ahead when he knows with near certainty that the Grand Canyon lies one foot away”.

These four major provisions have changed securities class action litigation. The PSLRA created important hurdles for plaintiffs while trying to balance investor protection with preventing abusive lawsuits.

The Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act of 1998 (SLUSA)

Congress found that there was a collateral damage shortly after PSLRA’s enactment: plaintiffs started bypassing the law’s strict requirements by filing securities fraud cases in state courts under state law. This shift made Congress pass the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (SLUSA) in 1998, which created a more unified framework for securities class action litigation.

Federal Preemption of State Law Securities Class Actions

SLUSA’s main goal was to federally preempt state law claims based on alleged misrepresentations, untrue statements, or omissions of material facts. These claims had to be brought in federal court. The core provision states that no “covered class action” can be managed under state law by private parties alleging “a misrepresentation or omission of a material fact in connection with the purchase or sale of a covered security”. The biggest problem was addressed by this preemption mechanism – most state class actions were being filed in California after PSLRA.

SLUSA defines “covered class actions” as lawsuits or groups of lawsuits that seek damages on behalf of more than 50 persons. A claim faces preemption when the misrepresentation becomes “material to a decision to buy or sell a covered security”. Federal courts would apply the heightened pleading standards and other PSLRA protections through this preemption.

Rule 10b-5 Claims and the Move to Federal Jurisdiction

Rule 10b-5 class actions moved to federal courts because of SLUSA, but Section 11 claims became ambiguous. One Supreme Court justice called SLUSA’s text “gibberish”, and this confusion lasted nearly two decades. Defendants could move SLUSA-barred lawsuits from state court to federal court for dismissal. This ensured federal courts could determine SLUSA preemption.

SLUSA’s jurisdiction provisions created an unusual situation in practice. State law claims faced preemption, but the statute didn’t clearly address the Securities Act of 1933’s concurrent jurisdiction provision. Some district courts required state law claims in federal court while allowing 1933 Act federal claims in state court. Other districts made all SLUSA-covered 1933 Act claims go to federal court.

How Forum Shopping and State Court Avoidance Were Affected

The Supreme Court unanimously decided in the landmark Cyan v. Beaver County case (2018) that SLUSA doesn’t remove state courts’ jurisdiction over class actions with only Securities Act claims. This ruling changed everything – Section 11 cases in state court jumped from 33 in 2016-2017 to 77 in 2018-2019.

A two-track system emerged: plaintiffs could bring Section 11 claims in state court and avoid PSLRA’s procedural safeguards, while Rule 10b-5 claims stayed exclusively in federal court. Class actions with only Securities Act claims couldn’t be moved to federal court by defendants.

Corporate defendants faced new challenges with this split system. Many Section 11 state court cases now have matching federal cases – these lawsuits target the same misleading statements but have different lead plaintiffs and sometimes extra claims. Companies now defend against duplicate litigation in multiple jurisdictions.

California state courts became especially attractive to plaintiffs after the Luther v. Countrywide Financial decision. Securities Act class actions in California increased by more than 1600% according to some reports.

The Class Action Fairness Act of 2005 (CAFA)

The Class Action Fairness Act of 2005 (CAFA) came into existence as Congress continued its efforts to reform class action litigation. This legislation aimed to redirect class actions from state to federal courts. Congress enacted CAFA on February 18, 2005, and it revolutionized class action litigation procedures in the United States.

Expanded Federal Jurisdiction for Large Class Actions

CAFA brought fundamental changes to federal jurisdiction over class actions by easing traditional diversity requirements. The old system demanded complete diversity between parties – every plaintiff had to be from a different state than every defendant. The new rules under CAFA introduced “minimal diversity,” which meant only one class member needed to be from a different state than any defendant. This change allowed federal courts to handle many more interstate class actions.

The law set specific thresholds for class size. Cases needed at least 100 members to qualify under CAFA. This requirement ensured federal courts would only handle large-scale class actions.

Courts received flexibility through CAFA’s discretionary exceptions. They could choose not to take jurisdiction when one-third to two-thirds of plaintiffs and main defendants were citizens of the state where the case started. Mandatory exceptions applied to cases where more than two-thirds of plaintiffs came from the filing state and at least one key defendant was local.

Aggregation of Claims Over $5 Million Threshold

CAFA introduced a novel approach to the amount-in-controversy requirement. The law raised the monetary threshold from $75,000 to $5 million and allowed the aggregation of all individual class members’ claims to reach this amount. This was different from traditional diversity jurisdiction, where at least one plaintiff had to meet the threshold individually.

Small claimants could now band together when their individual damages were modest but collectively represented major litigation. The aggregated claims could include compensatory damages, statutory damages, punitive damages, attorneys’ fees authorized by statute or contract, and equitable relief.

Defendants who want to move cases to federal court must prove the amount in controversy by a preponderance of evidence. CAFA made this process easier by removing the requirement for all defendants to agree to removal.

Exclusion of Securities Class Actions from CAFA Scope

Congress created specific exceptions for securities class actions despite CAFA’s broad scope. The law doesn’t apply to class actions “solely involving a claim concerning a covered security” as defined in the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Congress made this decision because PSLRA and SLUSA had already addressed securities class actions.

The exceptions also covered class actions about corporate internal affairs, governance, and those involving securities-related rights and obligations. These exclusions created complex interactions between CAFA, PSLRA, and SLUSA that led to ongoing jurisdiction debates.

The exclusion opened another potential loophole in securities litigation. The Ninth Circuit’s interpretation allowed cases with 1933 Act claims on non-covered securities to stay in state court. The Seventh Circuit took a different view, requiring all 1933 Act claims meeting CAFA’s requirements to go to federal court. This split between circuits created new opportunities for forum shopping.

CAFA changed the judicial system quickly and dramatically. A Federal Judicial Center study showed diversity class actions filed in federal courts jumped from about 12 filings monthly before CAFA to 34.5 afterward.

Cyan v. Beaver County and the Section 11 Exception

The judicial landscape for securities class action litigation underwent a fundamental change in 2018. The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Cyan v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund reshaped everything.

Supreme Court Ruling on State Court Jurisdiction

The Supreme Court made a groundbreaking unanimous ruling that changed the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (SLUSA). Justice Elena Kagan’s opinion for the Court stated that “SLUSA’s text, read most straightforwardly, leaves in place state courts’ jurisdiction over 1933 Act claims, including when brought in class actions”. This decision relied on statutory interpretation and reversed a 25-year trend that pushed securities class action litigation toward federal courts. The Court’s ruling prevented defendants from removing Securities Act claims from state court, which maintained concurrent jurisdiction between state and federal courts.

Post-Cyan Surge in State Court Section 11 Filings

Securities Act cases filed in state courts increased significantly after Cyan. State courts saw 75 cases filed in 2018-2019—a notable jump from previous years. New York courts’ new filings reached 30 cases, a stark contrast to earlier times when defendants moved Section 11 cases to federal court. The percentage of Section 11 cases filed only in federal court dropped from 88% (2011-2013) to 29% after Cyan. Plaintiffs preferred state courts because certain PSLRA provisions—like automatic discovery stay and lead plaintiff selection process—might not apply in state proceedings.

Parallel Federal and State Litigation Challenges

Cyan’s most challenging outcome has been the emergence of parallel litigation. Similar claims now proceed simultaneously in both state and federal courts. Recent data shows that parallel proceedings make up nearly half of all post-Cyan Securities Act litigation. No procedure exists to unite cases filed in different jurisdictions.

Cases with parallel proceedings in both state and federal court have an 82% settlement rate. This rate surpasses the 67% and 65% rates for cases filed only in state court or federal court. Defendants facing duplicate litigation across multiple venues face greater pressure to settle, whatever the case merits.

Modern Trends in Securities Class Action Litigation

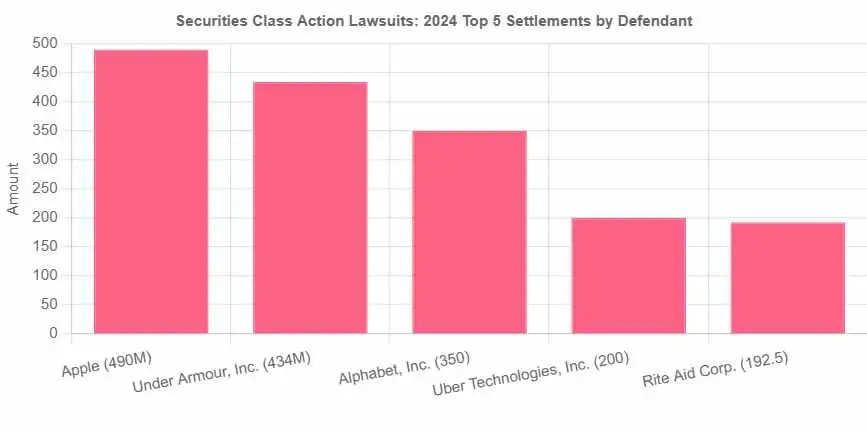

Securities class action litigation shows new patterns in recent filing data. Federal courts saw 229 new securities class action suits in 2024, matching 2023’s numbers. Technology and healthcare sectors made up more than half of all filings. The Second and Ninth Circuits represented 61% of cases.

Cybersecurity Breach Disclosures and Shareholder Claims

Data breach-related securities class actions have grown steadily since 2020. Companies face allegations of misrepresenting their cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Three of the top ten largest data breach-related settlements reached $560 million this year. These cases showcase a broader trend of “event-driven litigation” where stock prices drop after breach disclosures. The SEC’s 2023 cybersecurity risk management rules require companies to report material breaches within four days. Yet 73% of early filings didn’t indicate whether breaches had material effects.

ESG-Related Misstatements and Investor Lawsuits

BNY Mellon Investment Adviser paid a $1.5 million penalty after SEC charges for ESG-related misstatements. “Greenwashing” claims hit several companies hard. GrafTech International allegedly failed to disclose environmental contamination. Enviva Inc. faced accusations of misrepresenting its wood pellet products’ sustainability. The SEC’s Climate and ESG Task Force, established in 2021, has pursued multiple enforcement actions against companies making ESG-related misrepresentations.

Increased Role of Institutional Investors in Litigation Strategy

Institutional investors’ litigation strategies line up with their overall business goals effectively. Their participation boosts financial recovery and improves defendant companies’ corporate governance quality. Research shows lawsuits with institutional lead plaintiffs get dismissed 38.2% less often and secure 59.8% larger settlements. Some institutions now opt out of class settlements to file individual lawsuits as a stronger monitoring tool.

Conclusion

The world of securities class action litigation has changed dramatically since the 1929 Wall Street crash. This progress shows a delicate balance between investor protection and preventing costly frivolous lawsuits. The Securities Act of 1933 and Exchange Act of 1934 created the foundations for protecting investors. These 90-year-old mechanisms led to legal challenges that needed reform.

Congress took action with the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. This act introduced stricter pleading standards and discovery stays that altered the legal map. Plaintiffs adapted quickly by filing in state courts. This prompted more legislative action through the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act of 1998. The Supreme Court’s unanimous Cyan decision in 2018 cleared up many jurisdiction questions and caused a major surge in state court filings.

The Class Action Fairness Act of 2005 tried to move class actions to federal courts. Its securities case exemption created new complications. Companies now face growing problems from parallel litigation in multiple jurisdictions. This creates inefficiencies and often forces settlements regardless of case merit.

Recent trends show cybersecurity breach disclosures driving many securities class actions. ESG-related misstatements draw more regulatory attention and investor lawsuits. Institutional investors play bigger roles in shaping litigation strategy. They help improve financial recovery and corporate governance at defendant companies.

The securities class action system keeps changing with market and technology advances. The balance between helping defrauded investors and stopping abusive litigation remains unsettled. Future reforms must solve the problems of parallel state-federal proceedings while keeping valid investor protection intact. Companies must now direct their way through complex legal waters where disclosure choices carry major litigation risks. Investors depend on these legal tools to make corporations answer for their actions.

Key Takeaways

Securities class action litigation has undergone significant transformation since the 1929 Wall Street crash, with multiple legislative reforms attempting to balance investor protection against frivolous lawsuits.

• The PSLRA of 1995 raised the bar significantly – requiring heightened pleading standards, automatic discovery stays, and institutional lead plaintiffs to reduce meritless securities fraud cases.

• State court filings surged 1600% after Cyan v. Beaver County – the 2018 Supreme Court ruling allowed Section 11 claims in state courts, creating parallel litigation challenges.

• Modern securities litigation focuses on emerging risks – cybersecurity breaches and ESG “greenwashing” claims now drive many class actions alongside traditional fraud allegations.

• Institutional investors enhance case outcomes substantially – their involvement reduces dismissal rates by 38% and increases settlement amounts by nearly 60% compared to individual lead plaintiffs.

• Parallel state-federal proceedings create settlement pressure – companies facing duplicate litigation across jurisdictions settle 82% of cases versus 65-67% for single-jurisdiction cases.

The evolution continues as courts and legislators work to address jurisdictional inefficiencies while maintaining meaningful investor protection in an increasingly complex financial landscape.

Contact Timothy L. Miles Today for a Free Case Evaluation

If you suffered substantial losses and wish to serve as lead plaintiff in a securities class action, or have questions about

class action securities litigation

, or just general questions about your rights as a shareholder, please contact attorney Timothy L. Miles of the Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles, at no cost, by calling 855/846-6529 or via e-mail at [email protected].(24/7/365).

Timothy L. Miles, Esq.

Law Offices of Timothy L. Miles

Tapestry at Brentwood Town Center

300 Centerview Dr. #247

Mailbox #1091

Brentwood,TN 37027

Phone: (855) Tim-MLaw (855-846-6529)

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.classactionlawyertn.com

Visit Our Extensive Investor Hub: Learning for Informed Investors